The State of Black Education During COVID-19: the Good, the Bad, and the Promising

By Letisha Marrero

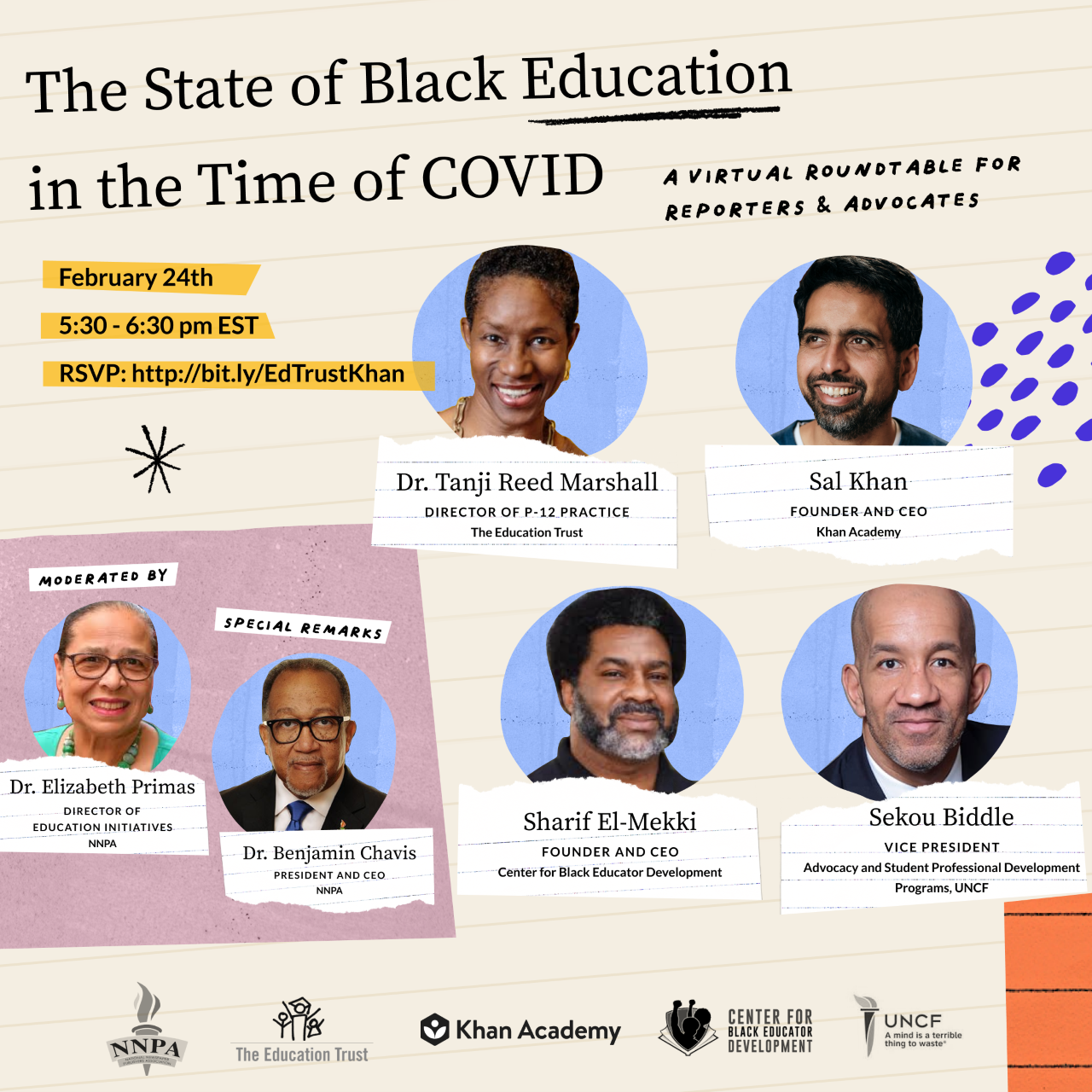

No doubt, the news about educating our children during a pandemic has been dire as of late, filled with doom and gloom. But to Black families, this is a familiar story. “Who was public education built for and who is it not?” asked Sekou Biddle, vice president, advocacy, and student professional development programs at UNCF. “Even what Thomas Jefferson said, ‘Education is an opportunity to rake the muck from the geniuses.’ We really haven’t moved far from that.”

Biddle was part of a panel of esteemed educators and leaders who gathered for a roundtable discussion on the state of Black education during COVID-19. The problem of systemic racism in public education has existed for centuries — it’s just now being exacerbated by things such as the digital divide and the lack of resources.

The media likes to tout it as “learning loss,” to make the problem sound even worse, but some people are actively trying to counter the narrative. “I don’t call it learning loss. I call it interrupted learning,” said Dr. Tanji Reed Marshall, director of P-12 practice at The Education Trust. “I want to make sure we don’t rest with the negative thinking that children are falling behind. They are standing on the precipice of possibility. They are eager to learn. We want them to not just be on track, but above the track.”

Parents right now are making critical decisions about whether to put their children back into buildings that may not be safe. While it’s true that some children are struggling with remote learning, others are actually thriving without having to deal with negative school climates, being bullied in school, or facing discipline disparities or implicit bias.

Sharif El-Mekki, founder and CEO of the Center for Black Educator Development, says that his focus is on teacher diversity, professional development, pedagogy for Black students that have been used for hundreds of years. “What we’ve seen is really an exacerbation of injustices for Black people. This pandemic on top of layers and layers of a racist endemic. The Black student experience and the Black teacher experience are intertwined.” His center just announced a new $3 million national educational justice campaign to dramatically increase the number of Black teachers entering the teaching profession.

Black teachers close educational achievement and opportunity gaps, decreasing dropout rates and increasing college enrollment of Black students by more than 30%. Given that Black teachers only comprise 7% of the teacher workforce, we need more of them. Black teachers understand what’s at stake for Black students and teachers given this crisis. “We need to build trust in our students,” said Magala Bien-Amie, a Black middle school special education teacher in Brooklyn. “I have all my kids on speed dial so if they’re absent, I’m right there. When I show up, I show up, and I never let them down.” She added that teachers need to be given the freedom to teach, because real-world problems need real-world solutions — and it’s not about teaching to the test. “I know we live in a high-stakes testing environment, but some kids are just not great test takers. You can’t let that be a barrier.”

When COVID-19 hit, teachers were “thrown into the deep end of the pool,” said Sal Khan, founder and CEO of Khan Academy. But now, teachers are embracing technology more and willing to use it moving forward. “I think we’re at a moment that no one would deny that everyone needs to have suitable internet access in this country. Instead of viewing it as gaps, I say start at grade level, and if you need to go back, do it at the same time. But that’s where digital tools like Khan Academy Kids can be valuable.”

The degree of unfinished learning caused by the pandemic will differ by student, subject, and grade —affecting math more than reading, younger grades more than older, and students already lacking adequate supports more than others. Marshall previewed some of Ed Trust’s upcoming research on three ways schools can give students the opportunities and supports they need to complete unfinished learning: targeted intensive tutoring, expanded learning time, and building strong relationships between students and strong school staff.

Biddle, who’s been a classroom teacher and is now a dad to a high schooler, says while parent engagement is a nice-to-have, this isn’t reality for a lot of Black parents who are essential workers. “Parents are the frontline. We’re asking parents to be counselors, and teachers are trying to do that remotely. We need to think about acceleration.”

Moving forward, educators will need to administer high-quality assessments to determine where learning must be accelerated and provide high-quality instruction to ensure students can reach high standards. Students will need access to opportunities, supports, and strong and supportive relationships. And targeted actions from school and district leaders and policymakers are needed to ensure stretched budgets do not result in policies and practices that harm the students who face the most injustices.

Said El-Mekki, “Black people have led in carrying the banner for educational and racial justice — two areas that are inseparable.”

And so, the march goes on.