have changed over time

By Zsana Hoskins

Special to the AFRO

In the wake of the Civil War and throughout the era of Reconstruction, the need for education in the Black community was evident. In response, historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) emerged, providing access to education when the doors of White institutions remained closed.

Among the first HBCUs were institutions such as Lincoln University and Cheyney University, both founded in the state of Pennsylvania during the mid-19th century. The focus was on teacher training. HBCUs recognized the need for qualified teachers and took on the responsibility of training educators who would educate future generations.

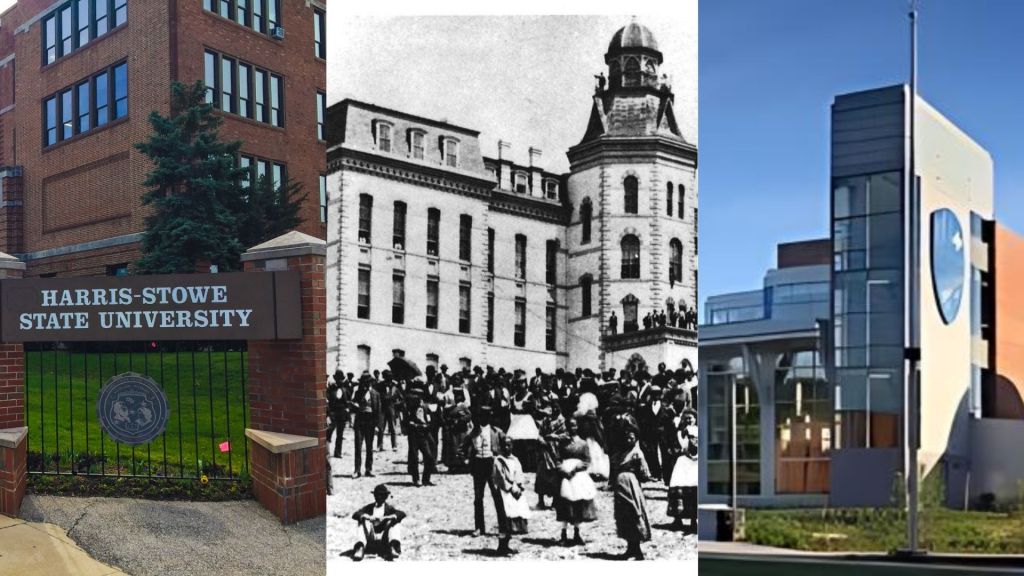

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and even still today, HBCUs faced numerous challenges, including limited funding, discrimination and legal barriers. Despite these obstacles, they persevered, expanding their curriculum beyond teacher education to include fields such as agriculture, engineering and the liberal arts. Today, there are 107 HBCUs with nearly 228,000 students enrolled. Over 75 of these institutions offer an education major, including Jackson State University, Howard University, Harris-Stowe State University, Delaware State University, and more.

The addition of new programs and concentrations allowed HBCUs to adapt to the evolving needs of their students and communities while continuing to develop Black educators. In the face of segregation and unequal access to resources, HBCUs became hubs of academic excellence and community leadership, as graduates went on to become not only educators but also civil rights leaders, scientists, artists and entrepreneurs, making significant contributions worldwide. Famous HBCU alumni include Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Thurgood Marshall, Toni Morrison, Chadwick Boseman and more.

Melanie Carter, Ph.D, the associate provost and director of the Center for HBCU Research, Leadership, and Policy, believes that the initial focus of teacher education that many HBCUs were founded on is relevant to the overall environments that cultivate leaders at these institutions to this day.

“The preparation of Black teachers at HBCUs has been critical to the creation of a

Black middle class, creation of expanded opportunities for our children and our communities. And these same teachers often serve as leaders in their communities. They serve as leaders in school,” said Carter.

The legacy of HBCUs as teacher training colleges continues to resonate today. While they have expanded their offerings to include a wide range of majors and concentrations, teacher education remains a staple of many HBCU programs.

HBCUs are still the top producers of Black educators in the country, despite only making up 3 percent of the colleges and universities in the country. According to a study conducted by the Howard University School of Education, HBCUs produce 50 percent of all Black educators nationwide. Cheyney University, founded in 1837 and recognized as the very first HBCU, upholds a reputation of training the largest percentage of Black educators in the commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

“We’re getting a lot of first-generation students who want to go into education because they want to make a difference in their communities. Cheney pulls from a lot of cities and a lot of spaces that have been traditionally coined as ‘high need’. use Cheyney as a stepping stone or a platform where they can go back into their communities and do some good,” shared York Williams. Ph.D, professor of early childhood and special education and coordinator of student teaching at Cheyney University.

Research even shows that teachers who graduated from HBCUs are more dedicated to their field. A study conducted by Donors Choice found that Black HBCU graduates spent over five hours per week on tutoring outside the classroom and six hours per week on mentoring, compared to four hours a week each, on the part of Black teachers who did not graduate from HBCUs. This could be linked to the overall environments and the emphasis on community at these institutions.

“Often at HBCUs, there’s an emphasis on looking at ourselves and our students and our communities from an asset versus a deficit model,” said Carter. “Being culturally grounded, understanding the importance of culturally relevant teaching–all those kinds of things are preparing young people to flourish in a society that was not intended to support their growth and development.”

Black teachers who are HBCU educated are also a major contribution to several issues in education, including the literacy gap.

“Black teachers generally work in urban areas. Having Black teachers in those places– who have had that experience– certainly helps with students. The teachers who we prepare are not any different than the students and communities they’ll be serving. part of the community and have shared a vision for our collective lives,” Carter added.

As the education system evolves, so do the programs at HBCUs. Williams highlighted the ways Cheyney’s curriculum has shifted its focus to ensure its graduates are well-rounded and can meet the needs of a variety of students they will encounter in the classroom.

“There’s more of a focus on ESL learners on students with special education needs. There’s also a response to the change in the literacy and math needs,” said Williams.

Cheyney also prepares its future educators through a curriculum that is up to the International Society for Technology (ITSE) standards and Pennsylvania’s Cultural Response of Sustaining Education Competencies (CRSD), which focus on diverse needs across culture, race, language and disability.

As we celebrate the rich history and contributions of HBCUs, it is essential to recognize their roots as institutions dedicated to the empowerment of Black people, particularly in the field of education.

“Even though the majority of Black students certainly attend traditionally White institutions, there are very few people, particularly people of color who haven’t been touched by the HBCU. Whether they’ve been your teachers, your dentists and doctors, your mother, your father, your cousins– we permeate every aspect of the nation. It is critical that HBCUs continue to do that so we have more opportunity for people to receive an education and go out and impact the world,” said Carter. “HBCUs are critical, certainly in terms of the teacher training space because teachers prepare our next generation.”

The post Humble beginnings: A look at how Black institutions in America appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers.