The first witness didn’t know where the heart was.

Nor did the second. Nor the third.

No answers as to the location of Brandon Clay Dotson’s heart came during a Friday morning hearing at the Hugo Black U.S. Courthouse in downtown Birmingham.

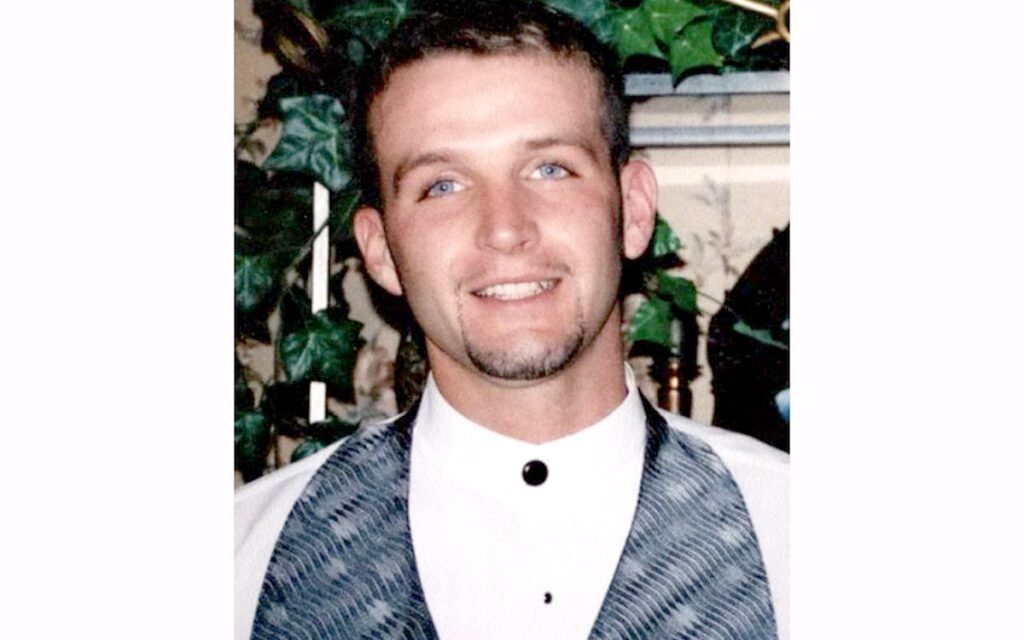

Dotson was found dead at Ventress Correctional Facility on November 16. The 43-year old’s family members — his mother, daughter and brother — claim in a federal lawsuit that they spent days trying to obtain his body. Once they did receive his body on Nov. 21., the family “suspected foul play, in part because of the Alabama Department of Corrections’ extensive and ongoing violations of basic human and constitutional rights,” said the lawsuit.

They hired a private pathologist to do a second autopsy on the body. That doctor, Dr. Boris Datnow, discovered during his exam that Dotson’s body was missing his heart.

The family filed a lawsuit after that revelation, suing the Alabama Department of Corrections, the Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences, and UAB Medical Center, arguing the heart was in some way received or planned to be received by the university. Dotson’s family is asking for the heart to be returned to them and to find out why it was removed in the first place, and under whose orders.

“The heart of a deceased person simply does not go missing in the absence of deliberate illegal activity or gross negligence on behalf of the entity or entities that had possession of the body prior to it being turned over to the family for burial,” said the family lawsuit.

On Friday, U.S. District Judge Madeline Hughes Haikala held a hearing in the case, trying to pinpoint where the heart currently is and why it went missing.

No answers came during the three-hour hearing.

Lawyers for the prison system said that Dotson’s heart was inside his body when it left the facility, and they do not have the heart.

The family’s attorney, Lauren Faraino, said the department is “shrouded in secrecy” and that Dotson’s mother had to use money from her retirement account to pay for the second autopsy.

“People forget we’re talking about a human being here.”

The fourth and fifth witnesses were no help either in locating the missing organ.

In all, five people testified during the three-hour hearing. They were: the warden at Ventress, where Dotson died; the commissioner and chief deputy commissioner of the Alabama Department of Corrections; the director of the Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences; and the head of autopsies at UAB.

All people who die in custody have an autopsy, said multiple prison officials. Some of those autopsies are done at UAB, while the rest are conducted at the state level by the department of forensic sciences.

But Dotson’s autopsy was performed by the Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences, testimony revealed.

And attorneys for UAB argued that no one from the school performed the initial autopsy on Dotson, nor had his body or organs ever been in their custody.

But the director of the Alabama Department of Forensice Sciences, Angelo Della Manna, said he hadn’t reviewed Dotson’s particular case file and couldn’t answer any questions about Dotson specifically.

He said that in a standard autopsy, a person will have their internal organs examined and then “sectioned,” or have pieces of tissue cut off, to be sent for further testing to determine cause and manner of death. The organs will then be put in a special biohazard bag and returned to their appropriate body cavity. The organs aren’t replaced in the exact place where they anatomically are located.

Those tissue sections are generally the only pieces of organs that would not be returned to the body, Della Manna said. He couldn’t name a reason why a fully intact organ wouldn’t be replaced in the body.

“I think we can probably get some insight on that… by looking at the document that’s currently available,” said the judge.

If any sections were sent for further testing, or if there was anything abnormal about the body, Della Manna said that information would be in Dotson’s case file and autopsy report.

That report hasn’t been provided to the Dotson family attorney and is not yet public.

Haikala ordered the state to provide that report for her to view privately by the end of the day Monday.

Lauren Faraino, the Dotson family’s attorney, said she believed the medical school was planning to receive the heart until the lawsuit was filed.

But a UAB attorney said in court that Faraino had “absolutely no evidence” to that, and added that the university is “certainly very sympathetic” to the Dotson family. UAB checked with the Alabama Department of Corrections and they had not sent Dotson’s body or organs to any UAB entity, according to court records filed in response to the lawsuit.

Lawyers for the school asked the judge on Friday to dismiss them from the lawsuit. “There’s really no reason for us to be here,” he said. “(It) just does not involve us.”