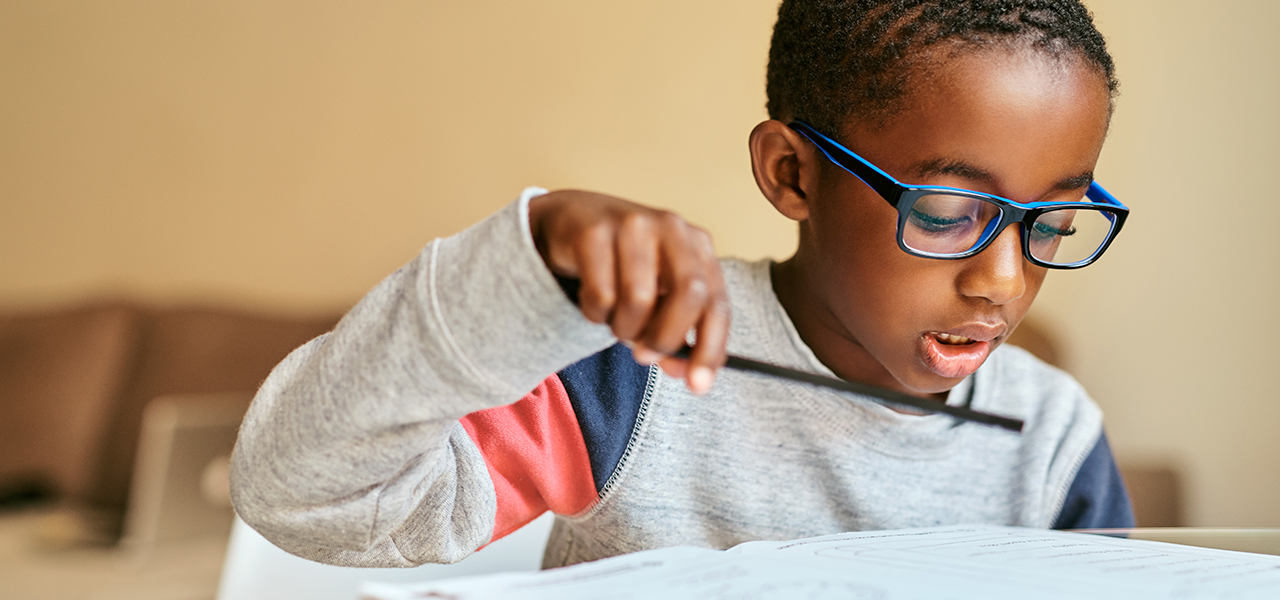

The publishing industry still has a great deal of progress to make concerning the representation of Black children and protagonists in books.

By by

While browsing the gift shop at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, librarian Kathy Lester watched a young Black girl grab a book and run up to her parents. Holding it up to them, the girl told them she’d read it at school, and it was one of her favorite books.

It was Grace Byers’ “I Am Enough,” which features a Black girl rocking her big, natural curls on the cover. Hearing kids speak like that shows there’s a connection, Lester says.

“If it doesn’t feel like the books reflect them, they pull away from it, like, ‘That doesn’t have anything to do with me,’” says Lester, who is also the president of the American Association of School Librarians. “Where, if they see themselves or find connections of themselves and books, then that helps inspire them to engage more and read more.”

In a 2009 TED Talk that’s been viewed 31 million times, Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie talked about the danger of a single story. When children don’t regularly see an accurate representation of themselves, it “sends them a powerful and harmful message that they do not belong,” explains Katie Potter, senior literacy manager at Lee & Low Books, a New York City-based publisher that’s been publishing diverse children’s books for the past 30 years.

“When children cannot find themselves reflected in the books they read, or when the images they see are inauthentic or negative, they learn a powerful lesson of how they are perceived in the world,” Potter says. “If readers cannot find characters who look like them and experience life in ways that they can relate to in the books they read, they can feel alone and isolated, all negatively impacting their academic engagement.

The number of children’s books by and about Black people has been steadily rising since 2018, when the Cooperative Children’s Book Center out of the University of Wisconsin-Madison started keeping a record. The rate was 17% in 2018, growing to 22% in 2021.

With the exception of Black authors, all diverse authors saw sizable drops in books published in 2020, followed by large increases in 2021. Plus, it can take years for a book to be published, so any progress made in 2020 or the following years might not be seen until 2022 or 2023, according to ABC News.

“The publishing industry still has a great deal of progress to make concerning the representation of Black children and protagonists in books,” Potter says.

Students who see themselves reflected in the books they’re reading are typically more engaged and curious about different things they can learn from a book, says Derrick Ramsey, co-founder of Young, Black & Lit, a Chicago-area nonprofit focused on increasing access to children’s books that center, reflect, and affirm the experiences of Black children. It’s important to see “the joys of life and the experiences of Black culture” in books, Ramsey says. It allows them to see things society might be telling them they can’t, Gage says.

“It makes them feel empowered and makes them feel like I can do this, too,” says Rochelle Levy-Christopher, founder and CEO of The Black Literacy and Arts Collaborative Project, highlighting the importance of cultural relevance. “If the story is based on things that we know about, that we’re familiar with … we get really excited because we don’t have that representation. So when we do, it’s that much more impactful.”

Lester echoes that, saying students need to “see themselves in books… and then be able to step in other people’s shoes” to help with a sense of belonging. But, especially for Black students, it’s not just about being represented in history-adjacent books but also in realistic fiction, fantasy, and graphic novels.

“Black children have the right to be in a world that includes them,” Potter says. “When Black children are exposed to and regularly engaged with texts that center Black protagonists and are written and illustrated by Black authors, they are validated, affirmed, and shown that they matter.”

Both The BLAC Project and Young, Black & Lit are working to make these books more available to children.

At The BLAC Project, giving away free books is only the beginning. They curate books based on every kid’s specific interests to make sure they’re getting things that will engage them. But the organization also runs programs and events to provide mentors and resources to help create a more equitable starting point between BIPOC communities and their white peers.

“We provide different types of literacy activities that don’t seem educational, but they are,” Levy-Christopher says. “They’re interactive, and they help bolster and improve literacy levels through different mediums in which the core focus is literacy comprehension.”

Young, Black & Lit also makes sure to get books out into communities that need them. As part of their donation program, they’re currently distributing 1,500 books every month to around 200 organizations across the country. One of their partners is Chance & Bri’s Books & Breakfast, featuring Chance the Rapper, which brings programs and giveaways to Chicago neighborhoods.

These organizations provide vital resources, especially during the summer months when it may be harder for students to access books.

“Although reading might be the last thing that children want to think about during the summer,” Potter says, “summer reading is important to keep their minds activated and on track for the start of the next school year.”

The post Here’s why Black kids need Black books appeared first on NNPA Education Public Awareness Program.