By Dr. Frances “Toni” Draper

AFRO Publisher and CEO

In my recently released book, “Prayer and Pen: The Prayers and Legacy of Carl Murphy, Publisher of the AFRO-American Newspapers 1922-1967,” you’ll find more than 100 prayers and commentaries on a variety of topics—including family, education, gratitude, freedom, faith, hope, love and labor—accompanied by photos from the AFRO’s extensive archives. Below are key points from the chapter titled “Labor.”

The AFRO’s role in documenting the Great Migration

For generations, the AFRO has chronicled the African-American labor experience, capturing defining moments in history with depth and integrity. Through its comprehensive weekly editions,the AFRO documented the Great Migration, serving as a guidepost for those seeking new opportunities in cities such as Chicago, New York and Baltimore. Between 1916 and 1930, more than 1 million African Americans left the agrarian South for the industrialized North in search of prosperity and equality.

In these bustling cities, migrants encountered a vastly different social climate from the Jim Crow South. Chicago’s growing Black neighborhoods, New York’s Harlem, and Baltimore’s expanding African-American communities became hubs of cultural renaissance and activism. Yet, they also faced immense challenges—crowded living conditions, employment struggles and the psychological burden of navigating racial barriers.

run in the AFRO in 1972. (AFRO Archives)

The Labor struggles of African Americans in Northern cities

Between 1916 and 1918 alone, approximately 400,000 African Americans moved north, drawn by labor shortages caused by World War I. Industries such as steel, automotive, locomotive, shipbuilding and meatpacking provided much-needed jobs. But for many, the migration was not just about economic opportunity—it was about dignity, freedom and the chance to escape systemic oppression.

A pivotal moment in the Black labor movement came in 1925 with the formation of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), led by A. Philip Randolph. The Pullman Company, renowned for its luxurious train service, was the largest employer of African Americans at the time. However, the company offered little opportunity for advancement while demanding grueling hours and requiring porters to pay for their own uniforms, meals and sleeping quarters. Worse still, they often endured demeaning treatment.

Randolph and his fellow porters fought tirelessly for fair wages and respect. For 12 years, they battled against entrenched racial prejudice within the labor movement. The American Federation of Labor (AFL) initially hesitated to support the BSCP, mirroring the discrimination of the era. Yet, the struggle of the porters became emblematic of the broader fight for African-American rights.

Carl Murphy, the AFRO’s publisher, highlighted how Jim Crow’s shadow stretched into the so-called “free North,” where segregation persisted in public transportation and other facets of life. The BSCP’s 1937 labor agreement was a landmark victory over discrimination and exploitation. Randolph, emerging as both a labor and civil rights leader, embodied the justice that the AFRO was committed to reporting. Through its extensive coverage, the AFRO ensured that the porters’ voices remained strong and their struggle widely known, reinforcing the connection between labor rights and civil rights.

The AFRO’s own labor history

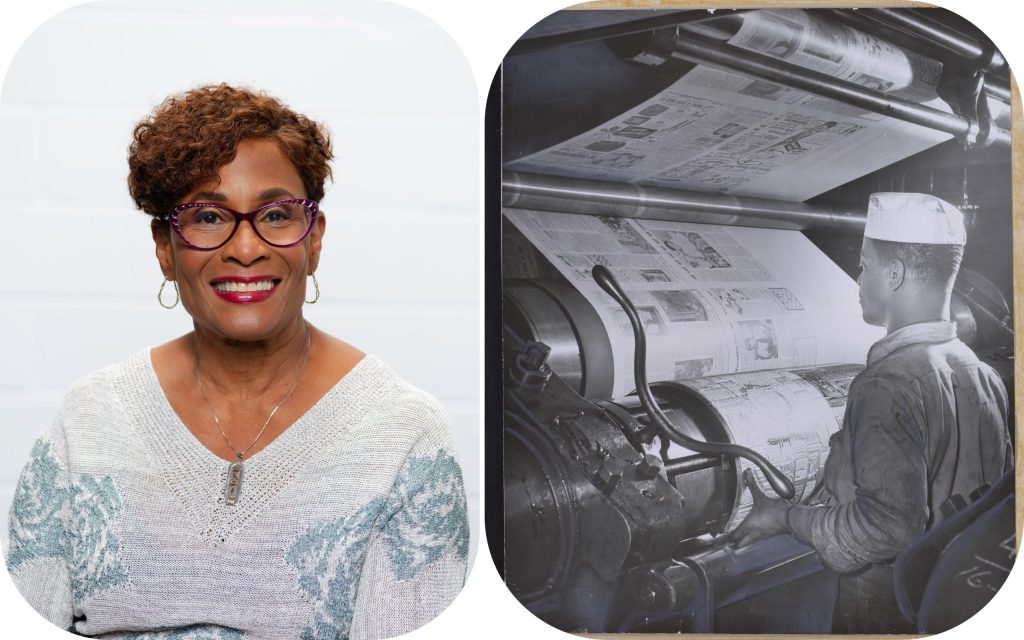

While the AFRO reported on labor movements across the country, it also maintained a unionized workforce for more than 70 years. The mechanical, composing, press and mailroom departments were all part of organized labor, and at one time, the newspaper employed more than 100 union workers.

Though the AFRO no longer has an organized labor union, we remain deeply grateful for our dedicated team members who work tirelessly to produce informative, relevant and engaging content for our readers. In an era when credible journalism is more critical than ever, our technologically savvy workforce continues to evolve with the latest advancements.

(AFRO Archives)

We extend our sincere gratitude to our readers and advertisers for your unwavering support as we continue the fight for diversity, equity and inclusion.

Prayers on work and labor by Carl Murphy

As we reflect on the significance of labor, we turn to the words of Carl Murphy, whose prayers remind us of the dignity and purpose of work:

Our Heavenly Father, we ask Thy special blessing on all those who work. Dignify their tasks, give them pride in the labor that they do, and make those who hire realize the importance of the humblest worker. Keep us kind and patient in this weekend of rest and recreation. Then start us once again—fresh and vigorous—to do Thy will and Thy work.

Dear Lord, when we work, give us a sense of joy. When we rest, give us a feeling of peace. When we come before Thee at the end of the day, grant us the satisfaction of achievement, the love of our home and friendships, and the knowledge that all we have is Thine—only loaned to us for a time.

Amen.

The post Working Together: How members of the Black Press and Black labor movement changed the world appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers.