By Ryan Michaels

The Birmingham Times

(Another installment in Birmingham Times/AL.com joint series on Gun Violence in the city)

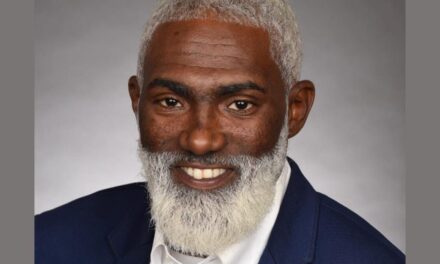

For the past 30 years, Felicia Mearon has worked in each of the city’s four precincts as a crime prevention officer (CPO) for the Birmingham Police Department (BPD), a position that has enabled her to connect and communicate with residents on all socioeconomic levels and a broad range of racial and religious backgrounds.

“You have to have that ability to reach out to all people because that’s who the BPD serves—we serve all people,” said Mearon, who has worked out of the West Precinct for about 18 years.

“I pride myself on making sure I can do everything in my power to improve the quality of life of the people in the communities I serve,” she added. “Even if it’s not a police issue, I do what I can to get that issue to where it needs to go in the city. … Any little thing I’m able to do is very rewarding.”

Community Liaison

The CPO position is a civilian role, so Mearon serves as the go-between for BPD and residents, which involves having a strong ability to maintain relationships with community members while working with law enforcement.

“It takes time, working and talking with people, and just reassuring them that the [confidential] information they give to me stays with me,” she said. “[I] help them address their concerns, and then I speak on behalf of the residents for the police.”

“But there’s a flip side,” Mearon added. “A lot of times, the residents think the police have authority, which they may not, so I have to speak for the police on that particular side. … [My position] gives me the opportunity to try and balance the two.”

Adlai Trone, president of the Fairview Neighborhood Association, said his community’s partnership with Mearon has been a benefit for residents.

“One morning, I saw a young lady on the corner, and she had a domestic violence relationship issue. I got [Mearon] on the phone, and she gave me options for resolving the situation. The young lady didn’t want to have any kind of dealings with the police department at all, but she was willing to communicate to me.”

After Trone shared the young woman’s story with Mearon, assistance was provided without going through the regular law enforcement channels, which allowed everyone to avoid escalating the situation.

Mearon’s CPO role is now more important than ever.

This year, Birmingham so far has seen 117 homicides through Tuesday Oct. 11 according to AL.com. Homicides in the city are up 33.3 percent this year versus the same time last year, according to the Birmingham Police Department. Currently, the city is on pace to reach nearly 150 homicides. The highest number in recent memory was 141 in 1991, according to AL.com’s Carol Robinson.

With those numbers seeming to increase daily, AL.com and The Birmingham Times will collaborate on a series of reports focusing on the contributing factors that may have fueled the high rate of homicides in 2022 and magnifying the voices of those who are affected by violence or working in areas to reduce some of the crime.

Additional reporting and storytelling will be provided on a biweekly or monthly basis, covering topics that include but are not limited to domestic violence, education, guns, and accountability. This partnership will also look at solutions offered by those who work daily in this space, including law enforcement, community activists, and mental health professionals.

Unique Perspective

Mearon’s experience in the community and working with residents gives her a unique perspective on gun violence.

“What we’re finding with the violence in the homicides is that they are so personal,” she said. “The victims [and] the suspects usually know each other, so it’s not impacting what we would consider to be the general public unless you’re just maybe in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

The CPO is also concerned about some of the music many young adults listen to.

“There’s a force [in some of the lyrics], a negative force, because the music is not positive. Some of it is, but the vast majority of it is not …,” she said.

Many residents are already on board with safer communities, but getting to those who aren’t on board can be a challenge, Mearon said: “How do you get to the ones [for whom] you’re not preaching to the choir? In my role, because I deal on the positive side of policing, anytime I talk about the [reducing] violence, I’m really preaching to the choir.”

Mearon offered advice to help residents make their communities safer.

“I encourage residents to reach out to the younger people in their families and try to touch them in a way that will move them in a positive direction,” she said.

“Come together as a group and do activities on the block. You’ve got to come out because that’s your visibility, the way you take back control of your block. You’ve got to come out of the house. In the summertime, I tell people, ‘Work in the yard.’”

She added, “You want to make sure you’ve eliminated that [criminal] element, so that you do feel safe to [come out]. … [Law enforcement] has ways that we anonymously work with residents to get rid of those elements.”

“A Win-Win”

Mearon grew up in the Brighton community and moved to Birmingham in 1993 after a divorce. She took the job as a CPO after teaching at the Bessemer Center for Technology on a two-year contract.

“’I never thought I would work for the police department,” she said. “The job came open, and it was mainly advertised as safety education training. I said, ‘Well, I’ve taught adults before, so maybe I could do this job.’ I just applied, and I got the job. After I got the job, the department trained me in terms of the information I needed that was applicable to the police department,” Mearon said.

The CPO role was created during the 1970s, when there was a division between the police and the Black community.

“Birmingham has been working on bridging the gap for a very long time,” Mearon said. “We’ve had issues to arise in Birmingham that could have led to full-blown rioting, but because of the relationship [CPOs] have with our community, we’re able to [avoid] the flames.”

Throughout her tenure with the department, within whatever quadrant of the city, and throughout the increase in gun violence, Mearon said her job has remained the same.

“My job is grassroots, and grassroots doesn’t change. People are people wherever you go. … and I still have so many good people,” Mearon said, adding that there has been a positive over the past three decades.

“I’ve made some friends over the years, so it’s been a win-win for me,” she said.