By John Sharp

Bryan Fuenmayor’s project last year to paint a massive Civil War cannon in Mobile set off a controversy that led to the City of Mobile deciding in February to pull all future permits for any group wanting to paint the structure.

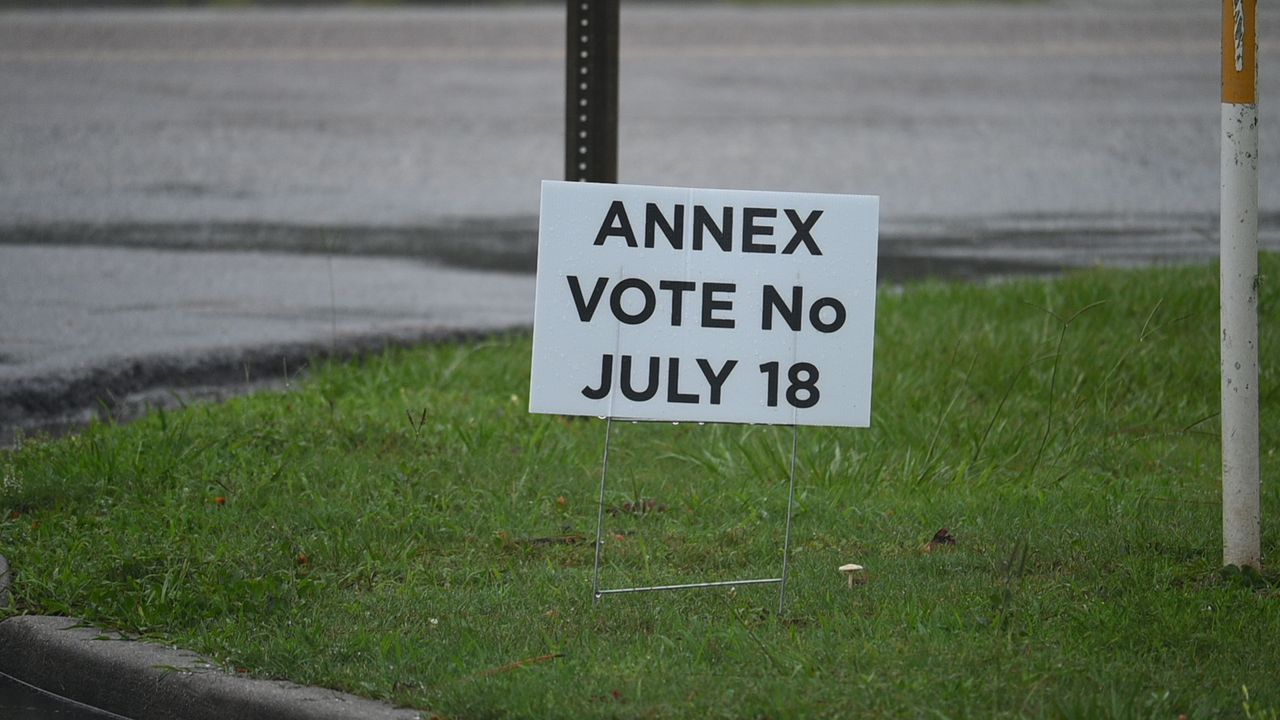

But Fuenmayor never anticipated the cannon’s rainbow-hued image becoming a culture war symbol and the unlikeliest of campaign issues thrust into the closing weeks of a 5-year-old debate over whether Mobile should annex close to 26,000 residents.

National polling suggests opposition to LGBTQ policies is resonating, especially among Republicans. And political observers and activists like Fuenmayor note that West Mobile is filled with Republican and conservative voters who will determine the fate on whether annexation is approved on Tuesday.

Opposition to public drag queen shows and LGBTQ Pride Month activities continue to animate in Mobile, less than a few weeks after the conclusion of Pride Month when a host of pastors – many of whom represent churches in west Mobile – vocalized their discontent with drag queen performances in city parks or libraries.

“West Mobile tends to vote Republican, and it could be that messaging is resonating with them,” said Fuenmayor, an LGBTQ activist in Mobile. “Typically, the Republican Party is anti-LGBTQ … it’s a love-hate relationship. But their overall platform is against same-sex marriage.”

Influential issue?

But is the appearance of an anti-LGBTQ billboard urging voters to reject the annexation plan part of a nationalized opposition campaign on an emotional social issue, or will it have no impact whatsoever?

Political scientists believe the campaign sign, supported by a group called Faith Freedom Family Coalition Metro Mobile, represents a “well-founded tactic in politics” aimed at stirring emotions ahead of an election.

“You will often find these tactics used when the issue being considered is complicated in nature,” said Jaclyn Bunch, an associate professor in the Department of Political Science and Criminal Justice at the University of South Alabama. “Most people are not experts in funding, tax, and urban development issues surrounding annexation. Thus, it is much easier to appeal to an emotional or moralistic issues which people have much stronger embedded sentiments about, in this case moralistic politics.”

Joshua Burford, director of outreach and lead archivist for the Invisible Histories Project – a historical archive for LGBTQ Southerners – agreed.

“This is an old tactic that has surfaced way too often lately,” Burford said. “It seems whoever these ‘Faith Freedom’ people are they are trying to confuse the local community by piggybacking on the hate speech that is all too common this year using the LGBTQ community as its focus.”

Not everyone believes the social issues will alter the annexation outcome.

Jon Gray, a longtime GOP political strategist in the Mobile area, said the real path forward for annexation supporters is securing enough voters, during a low-turnout election, who are concerned about the financial and economic issues of annexation:

- Concerns about future insurance rates

- Paying sales taxes at nearby stores at a higher city rate, but not receiving city services and unable to vote in city elections

- The prospects of no longer having city police or fire protection services.

“The only people walking through that analysis are the ones who have already accepted that they would be willing to accept philosophical differences between a metropolitan liberal-leaning city versus a very conservative, rural lifestyle,” Gray said. “The people opposed to the liberal philosophical issues of Mobile … they were never considering voting ‘Yes.’”

He predicts the pro-annexation forces, who have been campaigning on the issue for over four years, will likely get 55 to 60% of voters’ support. He does not believe the nationalized anti-LGBTQ policies will alter the outcome, though he said he would not be shocked to see annexation defeated.

The special election will take place in four different areas west of Mobile’s city limits. In order for Mobile to add close to 26,000 new residents – and become the second-largest city in Alabama – it will need a majority of voters in each of the four areas to vote in favor of annexation.

Church roles

The anti-LGBTQ push in Mobile is not just a reaction to nationalized issues. In Mobile, opposition has been brewing for months.

Looming large are a group of evangelical pastors, who have conveyed their worries over Mobile Mayor Sandy Stimpson’s administration’s appointment of LGBTQ liaisons last year, and the support of city government for Diversity, Inclusion and Equity policies.

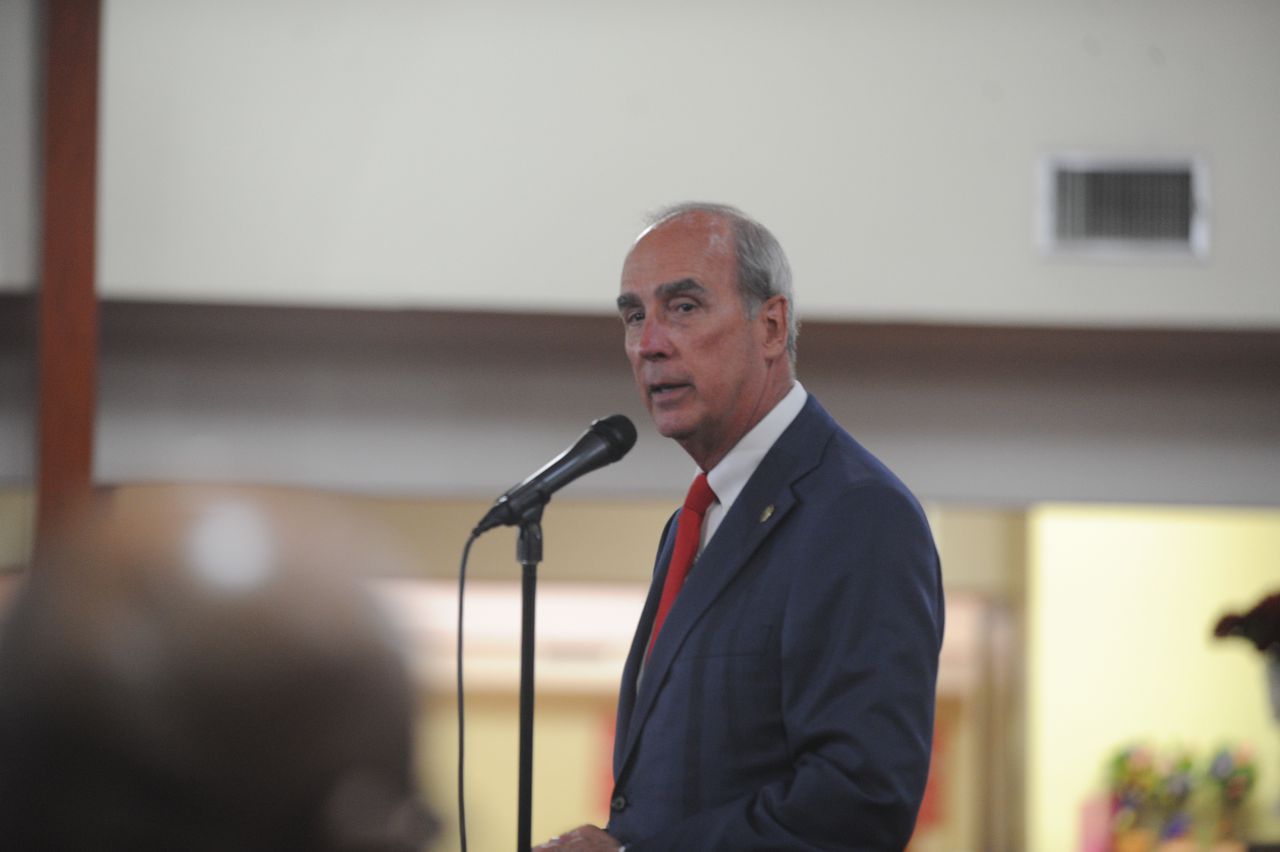

Stimpson, a Republican and the chief supporter for annexation, has enjoyed strong support in west Mobile during past city elections. His administration, for the first time in memory, is being criticized publicly for not being conservative enough on social issues, particularly on LGBTQ policies.

Pastors are publicly taking a hands-off stance on annexation.

The Rev. David Roach, pastor of Shiloh Baptist Church in Saraland and a representative with the Mobile Baptist Association, said the pastors within his association are not taking an official position.

The MBA comprises of 114 churches in Mobile County that cooperate with the Southern Baptist Convention. The group opposes same-sex marriage.

“Whatever the outcome of the annexation election, Mobile Baptists will continue urging the city to preserve religious liberty for all its residents and to refrain from using public funds for Pride celebrations,” Roach said. “We will stand with the mayor’s office in any work it does to uphold these priorities.”

The annexation vote comes a little more than one month after Pastor Travis Johnson of Pathway Church delivered a prayer at a Mobile City Council meeting that urged for the protection of children from “ideologies that have zeroed in on them.” Johnson also led a series of sermons at his west Mobile church entitled “Awake, Not Woke,” and criticized Visit Mobile for using taxpayer money to promote Pride Month celebrations.

Johnson was one of 43 Mobile pastors who signed a letter last month claiming that the “activist use of voter and taxpayer funds creates deep divisions among our citizens.” The letter likened drag performances in parks or libraries – both of which have occurred in Mobile – as a “form of grooming.”

The letter cites a Rasmussen survey that “only 29% of Americans” find drag performances at public venues appropriate. Rasmussen has long been criticized for having a pro-GOP bias.

Shifting opinions

But other polling suggests the Republican opposition to the LGBTQ movement is working. A Gallup poll from May showed a 7-point drop in the share of Americans who believe same-sex relationships are morally acceptable. Overall, 64% of Americans called same-sex marriage acceptable, down from a record-high 71% in 2022.

The drop is driven by Republicans. The Gallup poll showed that 41% believe same-sex marriage is morally acceptable down from 56% a year ago. The current figure among Republicans is the lowest Gallup has measured for the party since 2014, when it was 39%.

Opposition to LGBTQ rights and policies has been at the forefront of GOP politics for months, and has exploded this spring led by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a GOP presidential candidate in 2024, who has used the issue to drive his campaign.

A host of GOP-led state legislatures have passed a record number of restrictions on transgender rights, including Alabama. Stores like Target have faced criticism over their Pride Month merchandise.

Bud Light, a product of Anheuser-Busch, faced fierce conservative backlash over a marketing partnership with a transgender activist. Bud Light sales are down 28% from a year ago, according to reports.

Fuenmayor said the rising criticism against the LGBTQ community is sudden and swift. He coordinated a Drag Queen Story Hour event at the Ben May Main Library in downtown Mobile in 2018, drawing a large crowd of LGBTQ supporters. The same event drew only a handful of conservatives critical of the event.

He said it would be a different scenario today.

“For certain,” Fuenmayor said. “A lot of conservative politicians do not think for themselves. They get a script from these think tanks and go along with whatever the conversation is. Pride Art Walk wasn’t an issue until this year, and the public drag shows even longer than that. It wasn’t an issue until these think tanks said the drag queens were harmful to children.”

LGBTQ activists, though, say the inclusion of anti-LGBTQ campaign messaging – in a very local annexation vote – is a new strategy. But it’s also part of an old political playbook, they added, aimed at confusing the underlying issues.

“We always have to have one group to hate on,” said Patricia Todd, the first openly gay lawmaker elected to the Alabama Legislature and who served in the Alabama House from 2006-2018. “Whether it’s immigrants, people of color, and now it’s LGBTQ. It’s a very dangerous thing to see.”