By Gene Lambey

Special to the AFRO

According to the National Center for Health Statistics, “among men aged 18–44, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic men (6.1 percent ) were less likely than non-Hispanic White men (8.5 percent) to report daily feelings of anxiety or depression.”

Credit: Nappy.co/ Nathan McDine

The National Alliance on Mental Health (NAMI) has found that “Black Americans are often over diagnosed with severe mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia, and they are underdiagnosed for mood related disorders, like depression and anxiety.”

NAMI has also reported that African Americans are also “less likely to be offered medication for their diagnosis, even when appropriate and covered by health care.” The organization said that “implementing evidence-based screening and assessment tools that follow a biopsychosocial spiritual model — a treatment modality that takes into account biological, psychological, social and spiritual factors when assessing and treating an individual — will increase the efficacy of culturally sensitive diagnosis and treatment.”

The AFRO recently had the opportunity to speak about Black men and mental health with Rodney Orders, a licensed psychoanalyst with his own practice, Orders Counseling, located in Rockville, Md.

The expert works with patients who may be experiencing issues such as anxiety, depression and addiction. Orders Counseling offers martial, family and relationship counseling as well with a focus on “low-cost, excellent therapy” for families of color.

He works with adults, teens, children and couples, as well as with athletes, such as NFL players.

“The aim is to help clients gain understanding,” said Orders. “We can heal and resolve issues that come up for them.”

Orders provides cognitive behavioral therapy for his clients, and said that mental health resources should be more accessible to the Black community. He spoke on the need for Black-owned therapy practices, stating that many are owned by experts from non-Black backgrounds who may not understand the physical nor cultural differences of their patients’ environment.

“There is this lack of recognition or connection to the process just based on the absence of African Americans in the profession,” said Orders. “I think that the first thing that needs to change is more folks who are Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) going into the field. I think more education, especially in media form would also be helpful to destigmatize therapy for the Black community.”

Orders said that therapy should be normalized to a point where it is as common as an annual physical with a general practitioner.

“For a lot of Black people and BIPOC people, the world is tough enough with being ‘othered’ and marginalized,” he said.

“I think it is important to normalize therapy as a place where you can heal from intergenerational transmissions of trauma to the issues of White supremacy, hypervigilance and shame that comes with the issues around assimilation— which requires people to give up their specialness to fit in,” continued Orders. “All these things I’ve mentioned cause a different type of mourning in the Black community…therapy is a place we can build resilience as well as heal.”

Orders described the dangers of Black men holding their emotions inward, or internalizing what they feel, stating that it “leads to stress, leads to higher mortality rates, leads us to engage with risky behavior.” and added how it can lead to substance abuse. Orders noted that some turn to substances like drugs and alcohol as a coping mechanism because they “ haven’t learned better coping strategies.”

“To me, addictions are tools we use to try to reduce the harm that we’re experiencing and we don’t have the healthiest tools to reduce that harm. We seek out the things that are available to us or the things that we’ve seen our parents or grandparents to cope,” said Orders. “The harm is that we’re not communicating. We’re not building community around these particular issues –we’re dealing with it in isolation. If we talk about what’s going on with us, we’re more likely to gain access to those resources.”

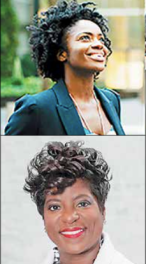

Earl El-Amin, president imam of the Muslim Community Culture Center in Baltimore, and vice president of Community and External Affairs at the National Center on Institutions and Alternatives (NCIA), is working to destigmatize mental health in communities of color.

He currently works alongside organizations in Baltimore like Black Men Unifying Black Men.

El-Amin spoke to the AFRO on the continued stigma around mental health and seeking therapy within the Black community.

“The experiences that we’ve had as Black men in America…I think that many of us need to have mental health services provided for us and we should seek them out,” said Earl El-Amin.

He listed organizations such as the Black Mental Health Alliance (BMHA), which helps connect community members with mental health services such as counseling and therapy.

El-Amin believes that consistent mental health services within the Black community looks like mental health services within Black neighborhoods, barbershops, recreation centers, schools and universities.

He said he wants to see more Black men seek help instead of holding on to their emotions, which can have detrimental effects to oneself and others as well.

“I think in many instances, we see that in domestic violence and in our neighborhoods. We see being unable to resolve disputes…lashing out. byproduct of not having that interaction with people that are close with you, that you can confide in,” El-Amin said.

El-Amin stated that most Black men keep an “arms length” on personal matters, but communicate with each other regarding their shared interests such as sports and women.

“We’ll delve into that, but we won’t really delve into what is really ailing us–we won’t confide in anyone, but we will talk about sports and sexual conquests,” said El-Amin.

El-Amin suggests that Black men take the time to work out and exercise together–walking, talking together and eating together. In his time, he’s found that “it helps the individual to loosen up.”

The faith leader said at the heart of it all is the feeling of connection and understanding.

“The best knowledge is the knowledge of the self,” he said. “The role of therapy essentially is to find the best part of you,” El-Amin explained. “Once you have a working knowledge of self, you are able to evolve and grow not just as a Black man but as a human being. That’s the crux of it.”

El-Amin said there are some self-help options that can be impactful as well. He recommends two books for all Black men to read: “The Invisible Ache,” by actor Courtney Vance, and “Visions of Black Men” by Na’im Akbar.

The post Therapy for men: How and why it helps appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers.