By Nadira Jamerson,

Word in Black

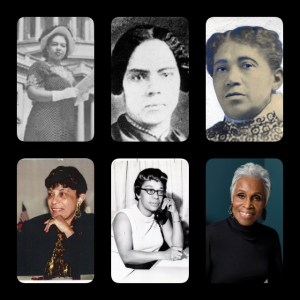

In the past few years, we’ve seen Ida B. Wells — one of the most prominent journalists, anti-lynching activists, and women’s rights activists in history — finally get the recognition she deserves.

The Ida B. Wells Society was launched in 2016. In 2018, the New York Times belatedly ran an obituary about her. And in 2019, after a campaign by Wells’ great-granddaughter Michelle Duster, Chicago finally named a street after Wells.

But have you heard of Mary Shadd Carey, the first Black woman to become a publisher in North America when she created The Provincial Freedman in 1850? Or Alice Allison Dunnigan, who in 1948 became the first Black female correspondent to receive White House credentials?

There is a long history of Black women who have not only contributed to but been leaders of the Black press. That’s why Ava Thompson Greenwell, professor at the Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communications at Northwestern University, says it’s time we give them their flowers.

“It’s important to situate them in the history and the importance they played at their Black press. These were owners, not just managers, but owners and publishers of these newspapers,” she explains.

Black women make up less than 5 percent of print and online newsrooms today. Greenwell believes teaching about the legacy of Black women publishers and increasing the visibility of Black women in the field is crucial if we want the next generation of Black girls to be inspired to join the profession.

“We know that patriarchy also runs deep within the Black community, and we have to uplift these Black women who are doing these things despite the sexism,” she says.

Greenwell recalls how learning about Daisy Bates, publisher of The Arkansas State Press, inspired her during her career. While researching for her doctorate, Greenwell took a deep dive into Bates’ life and admired her ability to weave activism through her journalism.

Bates was known for her coverage of Black men who were being unjustly railroaded in court as rapists and the coverage of Black women survivors of sexual assault whose cases were not being taken seriously. As a member of the NAACP, she advocated for the integration of Little Rock, Arkansas, in the 1900s.

“Those kinds of stories wouldn’t happen without Black women publishers,” Greenwell says. “What’s interesting about a lot of these women early on is that they were not just journalists and publishers. They were activists in their community. That’s the difference. Today, we say we have to separate the activism from the journalism, but these women didn’t see it that way. There was too much at stake.”

The need for more Black journalists — and more Black journalists — comes as attacks on Black history are sweeping the nation. More reporters who can amplify and uplift the Black experience are needed, especially at a time when Black books are being banned and prominent politicians are going to war against African American studies.

That’s why Greenwell says it’s time to rally behind the folks who have historically amplified the realities of the Black experience: the Black press.

“Journalism is the first page of history, and when it comes to Black journalism, it’s the same thing,” she says. “It’s a historical record of what Black people were doing and what was important to them at the time.”

This article was originally published by Word in Black.

The post The women behind the Black Press appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers .