By Bob Carlton

Marquis Forge has this thing that he does when he finds out someone has never tasted the crystal-clear, all-natural water that he bottles in his hometown of Autaugaville.

He takes them straight to the source — a free-flowing artesian well that pumps up to 125 gallons of water a minute.

Forge opens a valve and fills a plastic bottle with water that naturally flows from an aquifer several hundred feet below the surface.

He’s almost giddy as he watches his guest take a swig.

“Straight from the well,” he booms. “Hold it up. Look how clear it is. The lab calls that turbidity. No fog. Our water has no fog in it. Period. It comes out clear. Light transcends through it without any obstruction.”

He has good reason to be excited – about his water, yes, but also for his hometown.

Forge, who grew up in Autaugaville but moved to Tuscaloosa after he went away to college at the University of Alabama, came home and opened his Eleven86 Real Artesian Water bottling plant in April 2018.

In the three years since, the company has sold more than 17 million bottles of water to grocery and convenience stores throughout Alabama, as well as stores in California, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Maryland, Minnesota, Mississippi and Texas.

Most importantly to Forge, though, Eleven86 is putting people in his hometown to work.

“Everybody out there had never been in a bottling plant (before),” he says of his employees. “We all had the same years of experience — zero. Now, it’s a different story. We learned together.

“Our main goal is to keep those employees paid and working because they took a chance with us,” Forge adds. “They didn’t know anything about bottling water. They had to buy in.”

‘Won’t forget where I come from’

For Forge, this is all about keeping a promise he made more than 25 years ago.

The sixth of seven children, he was raised by a single mother, Jessie Adkins, who worked in Autaugaville’s since-shuttered Crystal Lakes Brooms & Mops factory.

“She never made more than about $135 a week,” Forge says. “I didn’t know we were poor until I went off to college.”

In elementary school, a severe speech impediment caused Forge to fall behind his classmates, but in the fourth grade, a hurtful remark by another student motivated him to prove his doubters wrong. His grades gradually improved over the years, and by the ninth grade, he was an all-A student.

At Autaugaville High School, he became president of the Student Government Association, the Beta Club, the Fellowship of Christian Athletes, and the Future Farmers of America — as well as a captain on the football team, where he played fullback and middle linebacker.

Forge graduated as the valedictorian of the Class of 1995, and in his graduation speech, he made a pledge to the people in his hometown.

“I got tired of seeing all the things that were bad happening to the town, and I made a promise within the speech that, hey, if I was to go off and become somebody — it doesn’t have to be much — I won’t forget where I come from,” he says. “And that’s really where the story begins.”

‘Don’t give up, keep going’

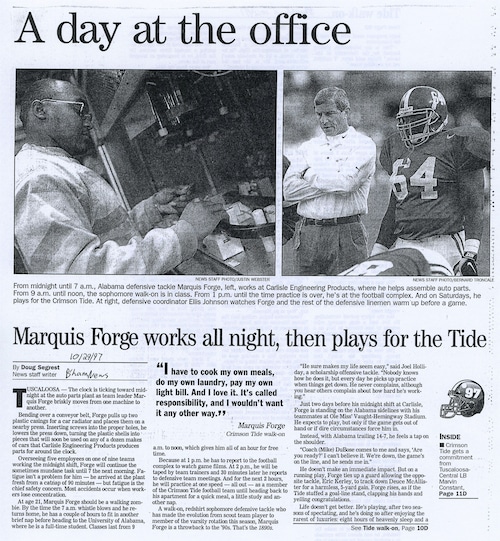

Forge attended the University of Alabama on an academic scholarship and was a walk-on for the Crimson Tide football team, playing defensive tackle under first Gene Stallings and then Mike DuBose.

Although undersized for a lineman, he worked his way from the scout team his freshman season to the travel squad two years later.

After the funding for his academic scholarship ran out, though, Forge had to go to work to pay for his tuition, books and living expenses. He got a full-time job working the graveyard shift at a Tuscaloosa automobile parts plant, and between juggling classes, football and work, he got by on about three hours of sleep a day.

“I worked from 11 to 7 at night,” he recalls. “Went to school from 8 to 2 in the daytime. And went to practice at 2:30 in the afternoon and got home at 7:30 at night. Went to sleep. Back up at 10:15 every night. I did that for two years.

“During that time, it taught me a lesson,” he adds. “It taught me just don’t give up, keep going.”

That’s also when Forge met his future wife, Nannette Gray, who also worked at the plant. She gave him a ride home one day after his car broke down, and they later started dating and got married in 1999.

A decade later, in 2010, Forge started his own company, Ingenuity Automotive Quality Solutions, which represented manufacturers who did business with the Mercedes-Benz assembly plant in Vance.

‘Look into this for me’

The divine series of events that led Forge to start his bottled-water business began in September 2015, when, while he was working in Tuscaloosa, his mother called to tell him a close family friend had died.

After he came home and paid his respects to the family, Forge was on his way to his mother’s house for dinner when he had what he calls an “I-kid-you-not” moment.

“I stopped at this stop sign to make a left to go to my mother’s house,” he recalls. “I’m waiting for traffic to clear, and God speaks to me. He tells me, ‘Go see Mr. Ward.’”

Francis B. Ward Jr. had been Forge’s principal at Autaugaville High School and was the former mayor of the town. Forge called to tell him he wanted to drop by to see him, and when Forge pulled up, Ward was on the porch waiting on him.

They talked, and Ward started telling Forge how much their little town needed a boost.

“I said, ‘Mr. Ward, what can I do to help the town?’” Forge says. “I kid you not, he looked at me and gave me the biggest smile and he said, ‘You can run a water-bottling plant.’”

They got in Ward’s truck and went for a drive, parking outside a water plant that had closed several years before.

Forge told his old principal that he already had a company to run and wasn’t interested.

“Why would I do this?” Forge asked.

“And he said, ‘Well, I’m going to pull one of my old favors out. Remember when you were in high school and went on a Beta Club trip? I bought you your first suit, didn’t I?’

“He said, ‘I need you to look into this for me, because I believe you can do it.’”

‘This is liquid gold’

Autaugaville, about halfway between Selma and Montgomery in Autauga County, is in an area that is blessed with an abundance of artesian water, a type of free-flowing spring water that comes from underground wells and moves to the surface naturally due to pressure.

Forge did some research and began to see the untapped potential in bottling Autaugaville artesian water.

“This place is just scattered with artesian wells,” he says. “And the thing about an artesian well, it runs constantly without any power. So, once you tap into it, it’s just like an oil well. It free-flows to the top under its own pressure.”

Forge inquired about buying that old water plant that Ward had shown him, but he and the previous owner were an ocean apart on the selling price.

So, after filling four spiral binders with notes, Forge decided to build his own plant instead, and he recruited his friend Kelvin Brickhouse, who worked in the automotive industry with Forge, to go into business with him.

“He said everything we needed was in one of his binders — all the notes he had taken and all the research he had done,” Brickhouse recalls. “So, I said, ‘Let’s do it; I’ve followed you this far.’”

They bought a few acres of property on County Road 165 in Autaugaville, cleared the land and dug a well.

When the lab tests came back on their water, Forge and Brickhouse knew they had tapped into something special.

“I’ll never forget,” Forge says. “We had the well tested (on) Oct. 6, 2016, and when the tests came back, they said, ‘This is liquid gold. All you’ve got to do is figure out how to put it in a bottle.’”

On a conference call that night, Forge says, his partners asked him: What are we going to name the water?

“I said, ‘I don’t know; God hasn’t told me yet,’” Forge remembers. “And they were like, ‘Well, you need to ask Him.’”

Forge prayed about it for a couple of nights. Finally, he came up with an idea: How many chapters are in the Bible? He searched an app on his phone and found his answer: 1,186.

One thousand, one hundred and eighty-six doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue, though, so Brickhouse suggested they call their water “Eleven86” instead.

A week or so later, though, Forge took it upon himself to go back and count all the chapters in the Bible, and he discovered he had made a mistake — that there are 1,189 chapters, not 1,186.

Rather than change the name, though, he and his partners decided to live with their mistake.

They all liked the sound of “Eleven86” better than “Eleven89,” and as Forge reasoned, since God created man on the sixth day, the number 6 at the end has a Biblical significance, too.

“We took off,” he says. “Never looked back. Never asked another question.”

After being turned down by 18 banks, Forge says, they were finally able to secure a loan from MAX Credit Union in Montgomery to finish building and equipping their 225,000-square foot bottling plant.

“I can’t tell you how many banks laughed at us, told us that we would never do bottled water,” Forge says. “MAX Credit Union was professional enough to come out and give us an opportunity.”

‘I’ve got to buy water, right?’

On April 27, 2018 — about two and a half years after Forge’s former principal called in that favor and nudged him to open a water plant — Eleven86 Real Artesian Water celebrated its grand opening.

Bama Budweiser of Montgomery and a few other Budweiser distributors around the state agreed to distribute the water in their markets, and over those last eight months of 2018, the company sold 632,000 bottles of water.

“That sounds like a lot, but it’s not a lot when you need 750,000 bottles a month just to break even,” Forge says. “We have this huge monster of a plant that consumes everything — the overhead, the equipment, our mortgage.”

In September 2018, Forge got an appointment with David Bronner, the CEO of the Retirement Systems of Alabama.

Forge had met Bronner the year before when he talked to him about getting RSA to invest in Eleven86. Although Bronner turned him down then, he told Forge to come back to see him if he ever got his company off the ground.

This time, Bronner said yes.

“He said, ‘Hey, my little water man got his plant going. . . . Now, I’ve got to buy water, right?’” Forge recalls Bronner telling him.

Bronner agreed to put bottles of Eleven86 water in every RSA hotel property in Alabama, including Renaissance Hotels in Birmingham, Montgomery and Mobile, as well as the Grand Hotel in Point Clear.

“RSA really was a catalyst for us,” Forge says. “So many different people that we couldn’t (otherwise) reach were able to go stay at one of the RSA properties and share and experience the water.”

The next year, in 2019, the Alabama Legislature designated Eleven86 and Autauga County artesian water as the official state water of Alabama.

“We’re on the same page as the longleaf pine tree, the camellia, the yellowhammer bird,” Forge says, referring to the state’s official tree, flower and bird, respectively.

Then, in 2020, when support for Black-owned businesses surged during the racial reckoning that followed the death of George Floyd, Eleven86 had its best year ever, selling 7.2 million bottles of water, Forge says.

“2020 was the first year Kelvin or myself or our partners didn’t have to take a portion of our paychecks and pay payroll,” Forge says. “I think we were about 12 truckloads from breaking even, but I tell you what, it was a whole lot better than 2018. We knew the power company cutoff man’s name personally in 2018.”

A little more than halfway through 2021, the company has almost matched sales for all last year, with 7 million bottles delivered through late July, Forge says.

“The grace of God and a lot of different things turned it around,” he says. “First of all, our customers. . . . We knew that, if we get the customers just to taste it, it’s over with.”

Eleven86 Real Artesian Water, which is sold in cases of 24 bottles, is now available in more than 500 locations in Alabama, include Food Giant, Piggly-Wiggly and some Winn-Dixie stores, as well as independent grocers and mom-and-pop stores.

The next biggest market, and one of the fastest growing, is Texas, where the H-E-B grocery store chain carries Eleven86 in about 115 locations in the Lone Star State. H-E-B also featured the Autaugaville artesian water in its Be the Change Initiative during Black History Month in February.

Closer to home, in Birmingham, Yo’ Mama’s Restaurant began serving Eleven86 water earlier this summer. The two businesses have also partnered to hand out free water to the city’s homeless population during the “Hydrate the ‘Ham” campaign in August.

Crystal Peterson, who co-owns Yo’ Mama’s with her mother, Denise Peterson, said she wanted to support Eleven86 after she discovered it was not only made in Alabama but also, like Yo’ Mama’s, is a Black-owned business. It is now the only bottled water they serve, Peterson says.

“I just want to be intentional,” she says. “If I sell a thousand bottles in two months, why would I not want to sell a thousand bottles of their water?”

‘Bottled in the sticks’

For Marquis Forge, the valedictorian of the Autaugaville High School Class of 1995, that graduation promise he made all those years ago has come to pass.

“We have something here that God blessed us with, that a town can be proud of,” Forge says. “When people think of Eleven86, they will always associate it with Autaugaville, Ala., and associate it with a promise that was made to help revitalize the town.”

One of the company’s employees, plant engineer Steven Gafford, has come up with a little jingle that he occasionally recites during his shift.

It is a nice reminder of the pride in ownership that he and the other employees take in the water they bottle.

“Straight from the ground; bottled in the sticks,” it goes. “Ain’t no water as good as Eleven86.”