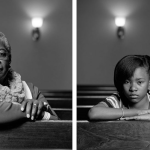

Mary Parker & Caela Cowan (Dawoud Bey Photo)

” data-medium-file=”https://www.birminghamtimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/DawoudBey-1–300×172.png” data-large-file=”https://www.birminghamtimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/DawoudBey-1-.png” />

By Ryan Michaels

For The Birmingham Times

Acclaimed photographer Dawoud Bey presents “The Birmingham Project” an exhibition of portraits at the Birmingham Museum of Art through Jan, 14, 2024 that commemorates the four young girls and two boys whose lives were lost 60 years ago in the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama.

As some of the youngest victims of the Civil Rights Movement, Addie Mae Collins (14), Denise McNair (11), Carole Robertson (14), and Cynthia Wesley (14) are memorialized along with Virgil Ware (13) and Johnny Robinson (16), two Birmingham boys who lost their lives as a result of the violence that followed the bombing.

To create the portraits, Bey photographed girls, women, boys, and men who currently reside in Birmingham. The subjects represent the ages of the young victims at the time of their deaths, and the ages they would be if were they alive today.

Along with the portraits, Bey also created a video shot in locations throughout Birmingham entitled 9.15.63. The video evokes the mood of that day: an ordinary Sunday morning, propelled into tragedy by senseless violence. Without specifically referencing the incidents, the project serves as a memorial to lives lost, a message of hope, and a promise for the future.

Bey began his career as a photographer in 1975 with a series of photographs, Harlem, USA, that were later exhibited in his first one-person exhibition at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 1979. He has since had numerous exhibitions worldwide. Bey’s works are included in the permanent collections of numerous museums, both in the United States and abroad

Here The Birmingham Times asks Bey about in-depth about The Birmingham Project exhibition and its impact on Bey and society.

What initially brought you to the idea of putting together an exhibition in commemoration of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing?

DB: The Birmingham Project began in a kind of epiphany moment. When I was 11 years old my parents brought home a book titled “The Movement.” This was a book of photograph of and about the Civil Rights Movement that had been published that year (1964) by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). They had gotten the book after attending a lecture by James Baldwin at the church we attended. After the lecture they bought the book, which was published and sold as a fundraising vehicle for SNCC. They brought the book home and eventually I decided to look at it. There were a number of horrific photographs in that book, including lynching photographs, but the image that seared its way into my psyche was a photograph of Sarah Jean Collins, the sister of Addie Mae Collins, one of the four girls killed in the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in 1963. She was lying in a hospital bed, her eyes covered in heavy gauze bandages, as she had been wounded in the blast that killed her sister and friends. I never forgot that picture from the moment I saw it. I kind of measure time in my life as my life before seeing that picture and my life after. It truly haunted me. Five decades later I was lying in bed one morning and that picture came rushing back to me, and I sat bolt upright in bed. It was such a strong feeling that I knew I needed to go to Birmingham and figure out how to make work in response to that horrific tragedy and that image that had never left me.

That began a series of visits to Birmingham, beginning with a weekend visit in which I visited the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. I had never been to Birmingham before and needed to see and bear witness to the place where this tragedy had occurred. Most of the projects that I had previously undertaken were done in conjunction with various museums. I had contacted the Birmingham Museum of Art prior to that visit to ask if they might be interested in working with me on an exhibition project centering on the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing and the death of the four girls.

Someone at the museum put me in touch with James Sokol, a member of the museum’s Sankofa Society, the African American support group. I got in touch with Jim and he began to introduce me to Birmingham and to some of the people who had been active in the Civil Rights Movement. Those visits went on for almost a decade before I began work, as I was in the midst of another project.

One of the first people Jim introduced me to on my first visit was Odessa Woolfolk, one of the founders of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, and someone who had been very active in The Movement. My conversation with the museum continued off and on over several years until at some point the then director Gail Andrews noted that in two years would be the 50th anniversary of the dynamiting of the church and that we should aim for that date as the date to open the exhibition. With a solid commitment from the museum, I started doing more serious research at that point. I felt that it was very important that the work be grounded both in research and relationships before I began making any photographs.

Earlier in your career, it appears that your work was more directly concerned with contemporary life and people, but that seems to have changed around the time of “The Birmingham Project.” Would you say that’s accurate, and if so, what do you chalk that up to?

” data-medium-file=”https://www.birminghamtimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/DawoudBey-2–203×300.png” data-large-file=”https://www.birminghamtimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/DawoudBey-2-.png” class=”size-medium wp-image-115015″ src=”https://www.birminghamtimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/DawoudBey-2–203×300.png” alt=”” width=”203″ height=”300″ srcset=”https://www.birminghamtimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/DawoudBey-2–203×300.png 203w, https://www.birminghamtimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/DawoudBey-2–284×420.png 284w, https://www.birminghamtimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/DawoudBey-2-.png 410w” sizes=”(max-width: 203px) 100vw, 203px” />

DB: The Birmingham Project marked a significant turning point in my work. As I began to think about what kind of work I could make that was equal to the weight of this history I wanted to engage, I realized that making conventional portraits would not suffice. Initially my idea was to make portraits of those young African Americans in Birmingham who were the same ages as the six young people who had been killed on that September Sunday in 1963. I had discovered from doing research at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute that two African American boys had been killed later that day along with the four girls who were killed in the church that morning. They were killed in separate racist incidences that had been ignited by the church bombing. So I knew I had to somehow represent the lives of those two young boys in addition to the girls. I wanted to give those six young people a more palpable and less mythic presence, to provide a powerful sense, thought the portraits, of just what a 12- and 14- year old Black girl looks like, and what a 13- and 16- year old Black boy looks like; to make them more palpable and less mythic. But that alone did not feel like it conceptually conveyed the narrative of lost lives and future possibilities cut short. So I decided to also make portraits of African Americans in Birmingham who were the ages that those young people would have been had they not been killed.

I thought that if I then joined these pictures—young person and older person—each diptych would embody 50 years, the number of years that had passed since their death, and I could then talk about both the past and the present in the work; to visualize the past in the contemporary moment. This idea of making work that embodied both past and present was a very new way of thinking about and making my work, as the individuals in the photographs both represented themselves but were also surrogate presences that represented those six young people. I decided to make the large-scale photographs in black and white as black and white is the material of photographic history, and I wanted history to materially cling to the work.

Is it possible you could lay out a rough timeline of the creation of “The Birmingham Project,” from your initial idea to the project’s exhibition?

DB: From that first visit until I began working in earnest in Birmingham took almost a decade. I remained in touch with the museum and with Jim Sokol over those years. While I was making exploratory and research visits to Birmingham, I was completing my “Class Pictures” project, photographing a cross section of American high school students across the country.

How did you find and select the subjects for “The Birmingham Project?”

DB: I worked closely with the museum to find the subjects. The Education department introduced me to several schools where I visited and talked to the students about the project, asking anyone who wanted to be photographed to talk to their parents and have them get in touch with us. Since they children were minors between the ages of 12 and 16, they could not grant their own consent.

For the adults I visited a local barbershop and beauty parlor, restaurants, and other places where people congregated, talking about the project and handing out flyers with information for those who might be interested, asking them to get in touch. The mayor invited me to speak before the City Council about the project since the City Council meetings were broadcast live on local television. We got some people that way. Individuals also hosted gatherings for me at their homes, invited people who were the ages that I was looking for to come, meet me, and hear about the project and to leave their information if they were interested in participating as subjects. It was a very wide-ranging kind of outreach, kind of “all of the above.”

It was pretty arduous as I wanted subjects who were the same ages—as young people or as adults—as the six young people who were killed. I thought it would have even more resonance if they were that age, rather than merely older or younger.

Your relationship with your photographic subjects is often highlighted when people talk about your work. Tell me about your experiences working with those you photographed in Birmingham.

In making my portraits over these many years I have what could be described as a momentarily intimate relationship with the person in front of the camera. In Birmingham it was different, because everyone I photographed understood that they were being photographed not only for who they were but also because of their relationship in age to one of the six young people killed in 1963. So this work was conceptually very different, and yet it was related since I have always tried to use my portraits as a space to represent Black interiority, the fact that Black people are not just social types but also have rich interior lives. It is this interiority, this deep and rich humanity that I have tried to convey in all my portrait work. In order to do that I need the person in front of the camera to engage with me as fully as I am engaging with them.

What I then do is to direct them to what one might call a heightened performance of themselves, to be themselves when fully present and to direct that towards the lens, allowing all of the picture making apparatus and equipment momentarily disappear. In this way the photographs also create a deep engagement with those who look at them once they are on the wall as their gaze meets the subject’s gaze. Scale is also important, so the photographs are large, almost life size, in order the further extend the presence of the individuals in the photographs into the space itself.

What was your thought process behind how the technique and processing of the photos and video would help in conveying the message of “The Birmingham Project?”

DB: I wanted both to provoke a sense of deep contemplation and reflection, to have the viewer momentarily be drawn back into that history, to remember and to reflect, to bring that past into the contemporary experience of the viewers.

Have you been to Birmingham since “The Birmingham Project?” If so, how has your relationship with the city changed since working on the “Birmingham Project?”

DB: I’ve been back to Birmingham numerous times since completing the project., spending time here visiting and keeping up with friends that I met when I first visited. I have a rich community here, friends that I consider to be family.

A little more than 10 years past the initial exhibition of “The Birmingham Project,” do you think that the exhibition and/or the collective memory of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing have shifted in their presence or importance?

DB: Even at the very moment that I was making the work in Birmingham Trayvon Martin, the young Black boy, was killed in Florida. I felt like I couldn’t make the work fast enough, for even as I was making this work to commemorate those young African Americans who were killed in 1963, they were still being killed. We are certainly still very much in a moment when African Americans continue to be the victim of racist violence, as we can see from recent and ongoing events. I feel that this project is as current as it ever was, and we still must address this issue of racist violence and the murder of Black people by those harboring racist sentiments.

What is visual art’s role in the sociopolitical realm, and how do you think “The Birmingham Project” fits into that? What were/are your ultimate aims with the work?

DB: If the visual arts have any role to be in contemporary sociopolitical society, it is to make people think, to make them more aware, more critically aware, more creatively aware, more alive to the possibilities of creative critical expression. I want my work to be a place where the human community can begin to have a conversation with itself, to have their senses heightened and to take something from the work that transforms them in some way. The visual arts can be a complex and provocative space to engage the imagination, for everyone to imagine themselves as more than they are, more connected than we sometimes think. James Baldwin said that “The precise role of the artist, then, is to illuminate that darkness, blaze roads through that vast forest, so that we will not, in all our doing, lose sight of its purpose, which is, after all, to make the world a more human dwelling place.” I agree.

What do you hope others will get from the exhibition this time in Birmingham?

DB: Hopefully this exhibition and this work will remind people that our failures to seriously engage with the messy history of this country only consigns us to repeat it.

“The Birmingham Project” an exhibition of acclaimed photographer Dawoud Bey portraits at the Birmingham Museum of Art through Jan, 14, 2024