By Deyane Moses

Special to the AFRO

In a groundbreaking initiative, Harvard University launched the Black Teacher Archive (BTA) in late 2023. This digital treasure trove offers a wealth of primary source materials – journals and newsletters – created by members of the Colored Teachers’ Associations (CTAs) between 1861 and 1970.

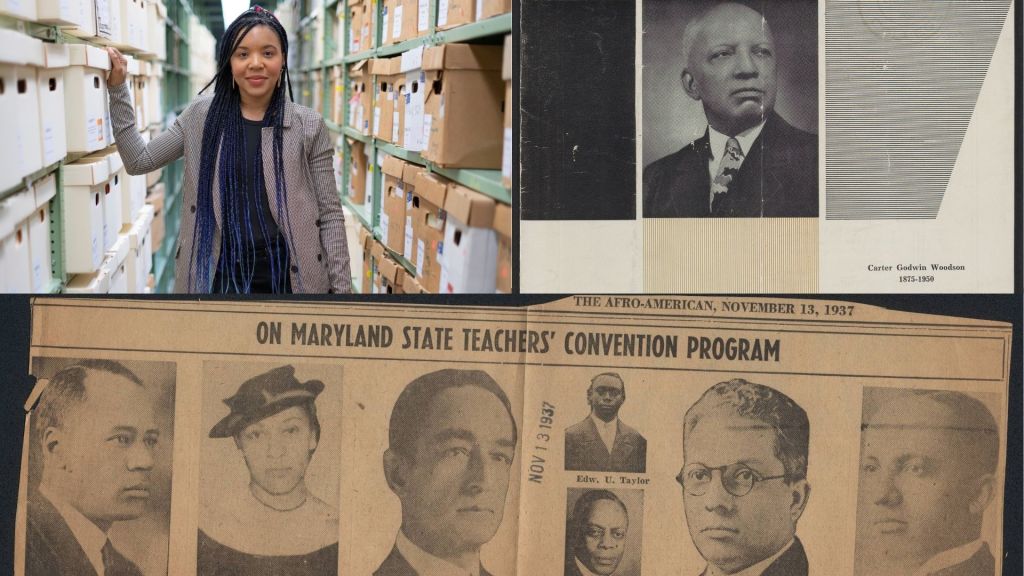

Dr. Jarvis R. Givens, a distinguished author and professor at Harvard who co-founded the BTA, reached out to Afro Charities in April about the treasure trove of information housed within the AFRO Archives. He was eager to explore the AFRO’s collection and discover if it held any materials related to the CTAs.

This fruitful collaboration led to a virtual discussion featuring Givens and Senior Project Manager, Micha Broadnax. The conversation delved into the significance of the BTA, particularly how providing access to these historical documents, created primarily by Black educators in segregated Southern schools, will revolutionize research in various fields – from the history of education to African American studies and critical pedagogy.

BTA is based at the Harvard Graduate School of Education in association with the Monroe C. Gutman Library Special Collections and is made possible through the generous support of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Spencer Foundation.

Moses: Thank you for joining me. Tell me a little about yourself. How did you come to the BTA?

Givens: The BTA grew out of my own research on Carter G. Woodson’s partnership with Black teachers, but also from collaborations with a colleague of mine, professor and co-founder, Imani Perry. Through our respective research we noticed the scattered existence of CTA materials in collections and decided we wanted to make them available in one particular place. Additionally, we are taking advantage of new technologies in terms of preservation when it comes to digital humanities.

Broadnax: I’ve worked in the archival profession for about 10 years and always wanted to center Blackness in my work. It was really great when I saw the call that Jarvis and Imani put out, recognizing the skill set an archivist or librarian can bring to the project. I’m just fortunate to be working with them to make this history more accessible.

Givens: The history offered through the Black Teacher Archive does two important things when it comes to current educators. First, it helps contextualize the current attacks on teaching truth within a much longer history, while also offering a tradition of teaching and teacher organizing that resisted such conservative factions in America schooling. Second, it allows teachers to go back and study this history. By understanding themselves as part of a much longer tradition grounded in study, scholarship and research, they can cultivate among themselves more empowered and historically informed professional identities.

Moses: Absolutely. The AFRO’s collection has an estimated three million photographs in addition to other ephemera, artwork and physical objects. What’s in the BTA’s collection?

Broadnax: The BTA is a digitally curated collection with material from over 70 institutions. In this first phase we are focused on journal publications. These publications were published at the state and national level, sometimes monthly or biannually. We are looking to expand the material to meeting minutes of these associations and track down any kind of photographs or audio visual materials that may exist that helps tell the story of these teachers associations.

We’ve been in contact with Afro Charities to help fill those gaps. In the collection, some states are better represented than others–particularly in the South. We are interested in seeing the coverage of northern and border state teachers associations within the Black Press.

Credit: Courtesy photo

Cut3: Jarvis Givens, Ph.D., professor of education and of African and African American studies is co-founder and director of the Black Teacher Archive at Harvard University.

Credit: Courtesy photo

Moses: Why is the BTA crucial for appreciating the ongoing contributions of Black teachers?

Givens: One of the most important things we’ve been finding in this research is the need to tell and retell powerful historical narratives about Black educators, because the archive is filled with them, yet public memory is quite impoverished when it comes to the legacy of Black teachers. The BTA showcases the amazing things Black teachers did to fight for educational justice in African American communities, especially for students. It provides a model of teachers who worked together, organizing to teach against the grain and push back against the aggression, and in many ways, violence they experienced; experiences that resemble what teachers are facing today. The BTA is crucial not just for understanding history, but also for inspiring effective organizing strategies for educators today.

Black educators, in particular, are often social justice-oriented educators within the profession. Many of them are called to the profession because they want to correct experiences they had, or they want to inspire young people the way they were inspired from those who came before them. This is especially important in this moment, when teachers overall are constantly under attack. It’s an unfortunate reality that we live in a time where many are discouraged from entering the teaching profession. We see this with teachers being targeted for teaching an inclusive curriculum, whether it’s African American history, gender or sexuality.

Moses: Is there an example of this in the BTA?

Givens: Of course. Lots of them. For instance, if we look in the 1935 Louisiana Colored Teachers Journal, we’ll see teachers organizing themselves into study groups by grade level where they’re reading emerging scholarship and literature by Black writers and Black scholars– and they’re doing this with the purpose of integrating this new Black scholarship into their classrooms. Of course, this was not formally sanctioned by Louisiana’s Board of Education. We find similar cases in other states.

Moses: How are researchers and institutions using the BTA?

Broadnax: The BTA is publicly available to anyone around the world at https://curiosity.lib.harvard.edu/Black-teacher-archive. Right now we have a lot of traction on our education history timeline. We’ve had K-12 teachers write to us about using it in the classroom and asking questions about how dates might correspond or conflict with their previous understandings.

Givens: There’s a variety of people engaging with the collection. We’ve had some folks inform us about things they’ve found in the BTA which they’re now incorporating in books, other writings, and in the classrooms. These are particularly scholars in higher education who have been able to incorporate the BTA into their courses on the history of African American education. We are hoping to see more of this, in African American studies, teacher education and history courses.

Broadnax: The BTA is also a resource for genealogical research for both educators and students. I often ask my mom and her friends to tell me about teachers from their school days. The records demonstrate their teachers’ network, organizing, or professional development and how that might translate to how they experienced those instructors. It’s a wonderful resource.

Givens: Absolutely.

The post Teaching against the grain: The Black Teacher Archive as a blueprint for educator organizing appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers.