By SHARON LURYE and REBECCA GRIESBACH

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. (AP) — Everywhere, it seems, back-to-school has been shadowed by worries of a teacher shortage.

The U.S. education secretary has called for investment to keep teachers from quitting. A teachers union leader has described it as a five-alarm emergency. News coverage has warned of a crisis in teaching.

In reality, there is little evidence to suggest teacher turnover has increased nationwide or educators are leaving in droves.

Certainly, many schools have struggled to find enough educators. But the challenges are related more to hiring, especially for non-teaching staff positions. Schools flush with federal pandemic relief money are creating new positions and struggling to fill them at a time of low unemployment and stiff competition for workers of all kinds.

Since well before the COVID-19 pandemic, schools have had difficulty recruiting enough teachers in some regions, particularly in parts of the South. Fields like special education and bilingual education also have been critically short on teachers nationwide.

For some districts, shortages have meant children have fewer or less qualified instructors.

In rural Alabama’s Black Belt, there were no certified math teachers last year in Bullock County’s public middle school.

“It really impacts the children because they’re not learning what they need to learn,” said Christopher Blair, the county’s former superintendent. “When you have these uncertified, emergency or inexperienced teachers, students are in classrooms where they’re not going to get the level of rigor and classroom experiences.”

While the nation lacks vacancy data in several states, national pain points are obvious.

For starters, the pandemic kicked off the largest drop in education employment ever. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of people employed in public schools dropped from almost 8.1 million in March 2020 to 7.3 million in May. Employment has grown back to 7.7 million since then, but that still leaves schools short around 360,000 positions.

“We’re still trying to dig out of that hole,” said Chad Aldeman, policy director at the Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University.

It’s unknown how many of those positions lost were teaching jobs, or other staff members like bus drivers — support positions that schools are having an especially hard time filling. A RAND survey of school leaders this year found that around three-fourths of school leaders say they are trying to hire more substitutes, 58% are trying to hire more bus drivers and 43% are trying to hire more tutors.

Still, the problems are not as tied to teachers quitting as many have suggested.

Teacher surveys have indicated many considered leaving their jobs. They’re under pressure to keep kids safe from guns, catch them up academically and deal with pandemic challenges with mental health and behavior.

National Education Association union leader Becky Pringle tweeted in April: “The educator shortage is a five-alarm crisis.” But a Brown University study found turnover largely unchanged among states that had data.

Quit rates in education rose slightly this year, but that’s true for the nation as a whole, and teachers remain far more likely to stay in their job than a typical worker.

Hiring has been so difficult largely because of an increase in the number of open positions. Many schools indicated plans to use federal relief money to create new jobs, in some cases looking to hire even more people than they had pre-pandemic. Some neighboring schools are competing for fewer applicants, as enrollment in teacher prep programs colleges has declined.

The Upper Darby School District in Pennsylvania has around 70 positions it is trying to fill, especially bus drivers, lunch aides and substitute teachers. But it cannot find enough applicants. The district has warned families it may have to cancel school or switch to remote learning on days when it lacks subs.

“It’s become a financial competition from district to district to do that, and that’s unfortunate for children in communities who deserve the same opportunities everywhere in the state,” Superintendent Daniel McGarry said.

The number of unfilled vacancies has led some states and school systems to ease credential requirements, in order to expand the pool of applicants. U.S. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona told reporters last week that creative approaches are needed to bring in more teachers, such as retired educators, but schools must not lower standards.

Schools in the South are more likely to struggle with teacher vacancies. A federal survey found an average of 3.4 teaching vacancies per school as of this summer; that number was lowest in the West, with 2.7 vacancies on average, and highest in the South, with 4.2 vacancies.

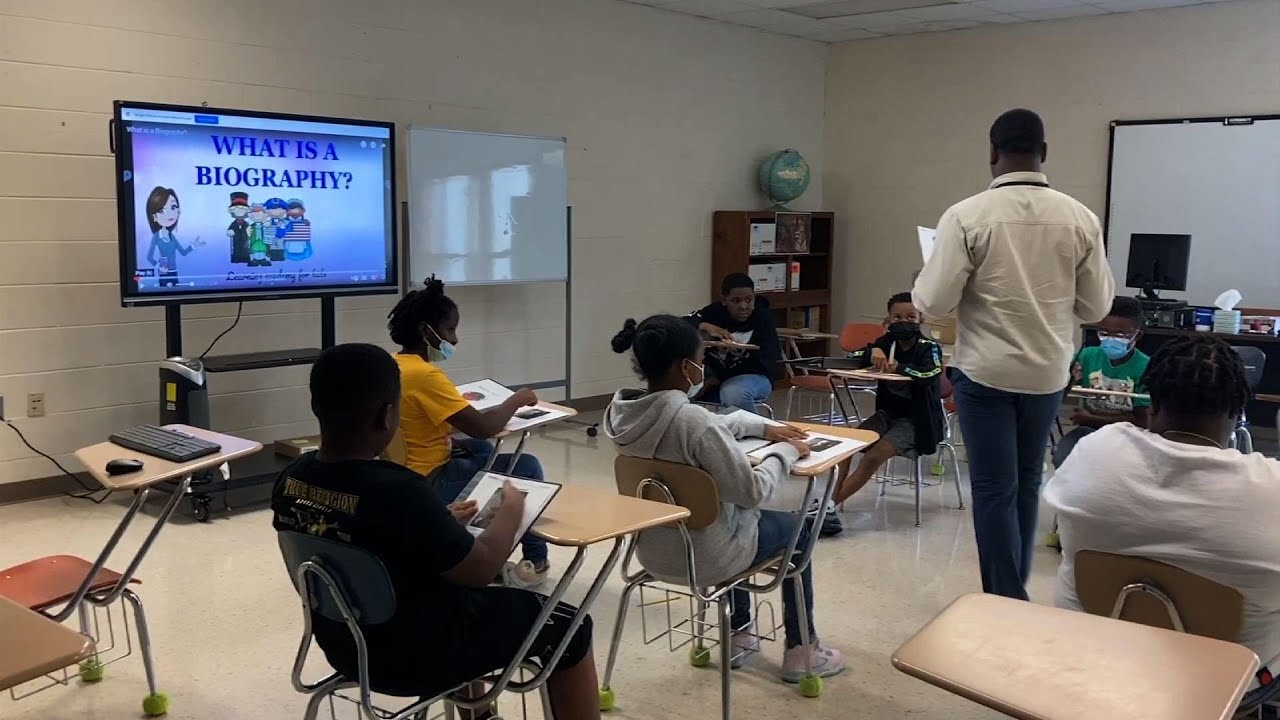

In Birmingham, the school district is struggling to fill around 50 teaching spots, including 15 in special education, despite $10,000 signing bonuses for special ed teachers. Jenikka Oglesby, a human resources officer for the district, says the problem owes in part to low salaries in the South that don’t always offset a lower cost of living.

The school system in Moss Point, a small town near the Gulf Coast of Mississippi, has increased wages to entice more applicants. But other districts nearby have done the same. Some teachers realized they could make $30,000 more by working 30 minutes away in Mobile, Alabama.

“I personally lost some really good teachers to Mobile County Schools,” said Tenesha Batiste, human resources director for the Moss Point district. And she also lost some not-so-great teachers, she added — people who broke their contracts and quit three days before the school year started.

“It’s the job that makes all others possible, yet they get paid once a month, and they can go to Chick-fil-A in some places and make more money,” Batiste said.

A bright spot for Moss Point this year is four student teachers from the University of Southern Mississippi. They will spend the school year working with children as part of a residency program for aspiring educators. The state has invested almost $10 million of federal relief money into residency programs, with the hope the residents will stay and become teachers in their assigned districts.

Michelle Dallas, a teacher resident in a Moss Point first-grade classroom, recently switched from a career in mental health and is confident she is meant to be a teacher.

“That’s why I’m here,” she said, “to fulfill my calling.”