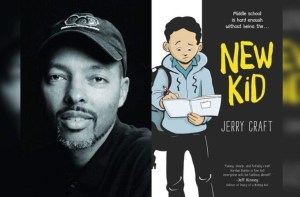

Kendall Thornton III will always have a piece of his older brother because they share the same name. Kendall Jarrod Thornton Jr. was found shot to death in his crashed vehicle on Sunday, Nov. 6, 2022. (Amarr Croskey, For The Birmingham Times)

” data-medium-file=”https://www.birminghamtimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/lead01-300×194.jpg” data-large-file=”https://www.birminghamtimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/lead01-1024×662.jpg” />

By Alaina Bookman

AL.com

This is another installment in The Birmingham Times/AL.com/CBS42 joint series “Beyond the Violence: What can be done to address Birmingham’s rising homicide rate.”

This is the first year that Kendall Thornton Jr.’s family has celebrated Thanksgiving since his death on Nov. 6, 2022. He was 21.

“Everybody was just confused still,” said his brother, Kendall Thornton III. “Christmas came [last year], and we tried to get together, but it just…holidays ain’t going to feel the same. It really hit us hard.”

Birmingham’s homicide crisis has left families broken. Around the holidays, in particular, loved ones say empty chairs and untold jokes can be hard. Those who have lost siblings, like Kendall Thornton III and others, interviewed for this article, say their lives will never be the same.

According to a survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation, an estimated one in five adults across the U.S. said they have had a family member killed by a gun, including suicide. One in six adults polled said they have witnessed a shooting. The survey of 1,273 adults also found that the vast majority of respondents said they worry at least sometimes that they or someone in their family will become a victim of gun violence.

That’s one of the reasons Cordarrell Peak moved to Huntsville, Alabama, after his 21-year-old brother, Calvin Foster, was killed in Birmingham seven years ago.

“I ended up getting shot literally a year after my brother got killed,” Peak said. “My mom feared losing another son.”

As Birmingham residents continue to grieve their lost loved ones, experts suggest continuing the conversation about the impact of violence on individuals and communities.

Daniel Marullo, Ph.D., a pediatric psychologist and neuropsychologist with Children’s of Alabama, said some people experience secondary victimization, such as a sibling experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, irritability, appetite changes or sleep disturbances after suddenly losing a brother or sister.

“People are at higher risk if they’re closer to the event, for example, [if it involves] their brother or sister or somebody they were particularly close to,” he said. “If they live in areas that have a lot of violence, it puts them at even a higher risk for distress.”

Cassandra Crifasi, Ph.D., co-director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions, told AL.com that violence and crime are often concentrated in communities where high-quality education, jobs and housing are to find.

In addition to policies that would address gun violence specifically, Crifasi said communities should also consider public health solutions such as violence intervention programs and street outreach that bring in the whole community.

“It’s beyond the individual,” Crifasi added. “Communities that experience high rates of gun violence are just absolutely ravaged by this issue, and it has long, long-standing effects.”

Three siblings who have lost their brothers to gun violence in Birmingham were asked to share their stories as part of The Birmingham Times/AL.com/CBS42 joint series, “Beyond the Violence: What Can Be Done to Address Birmingham’s Rising Homicide Rate.”

Kendall Thornton

Kendall Thornton III will always have a piece of his older brother because they share the same name.

He said his brother, Kendall Thornton Jr., 21, was a “stand-up guy,” quiet and introverted but easy to talk to. Around his family, he was funny, goofy and laid back.

“He balanced everything out in the family,” Thornton III said.

The Thornton brothers loved to travel, visiting Atlanta, Georgia; Florida’s Destin Beach and Panama City Beach; New Orleans, Louisiana; and New York City together.

“My favorite memories were our trips to Atlanta,” Thornton III recalled. “We really just went on spending sprees. We would go through the mall, and I would see him having fun. He would get hype when he would get his clothes.”

During an interview in mid-November at his father’s house in Center Point, Alabama, Thornton III smiled and chuckled as he remembered running through Times Square, in New York City, with his brother at 4 a.m. to catch a flight home. He was 19, and his brother was 20.

“That was a real fun memory with that boy,” he said. “It just brightened your day up to watch him do stuff. You just gotta laugh at him. He was a fun dude.”

Kendall Jarrod Thornton Jr. was found shot to death in his crashed vehicle on Sunday, Nov. 6, 2022.

Thornton III has not sought counseling, but he has turned to meditation, and he often confides his feelings and memories to his mother, Angel.

“We just have to continue being strong, have each other’s backs, until our day comes,” he said.

Thornton III, 21, said his brother’s death changed him. He feels survivors’ guilt for not being there for him.

“I’m not open anymore. It’s really hard to trust people. I just look at life with a different perspective,” he said. “It used to be about getting a goal done, but as the months went by after [my brother] died, it went from getting goals done to just living day by day.”

“When you’re with somebody your whole life, by your side, and they just disappear, it messes you up mentally,” Thornton III added.

On the anniversary of Thornton Jr.’s death, Thornton III visited his brother’s gravesite at Zion Memorial Gardens Cemetery, talking to him and spending some time alone with him. Later in the day, he met with family for a balloon release.

“We’re definitely going to be having fun for his birthday,” Thornton III said. “It’s not going to be a sad moment, or we’ll try not to make it a sad moment because he wouldn’t want that for us.”

Thornton III has his brother’s birthday, Dec. 28, tattooed across his neck.

Thornton III, who has a daughter due to be born in December, said he looks forward to taking her to his brother’s grave and telling her about her uncle.

“He left a lot behind. I just know he had a lot ahead of him, too. He left a strong legacy behind. He was doing his purpose while he was here, just being that guy for you, being there for you,” Thornton III said. “As a sibling, he was always there for me. He showed me what a true sibling was, what a true friend was, too.”

Kendall Thornton Jr.’s death is still unsolved, and his brother asks those who know anything about the shooting to come forward.

“Nonsense killing is wrong, innocent lives taken away. I just feel like we need to know who’s behind it,” said Thornton III.

Cordarrell Peak

Cordarrell Peak is the spitting image of his brother, Calvin Foster. Sitting beside a candle burning in front of his brother’s photograph and obituary, he remembers what life was like before Foster was shot and killed on Aug. 9, 2016, at the age of 21.

“Life now is hard, especially on holidays,” Peak said. “Life now for me goes on, but I will never see him again.”

“The pain, the feeling, the memories, they never leave. It’s hard living without my sibling that I grew up with. Life now, it will never be the same without him, ever,” Peak added. “All the memories, that’s all I have left—pictures, obituary, a tombstone, that’s it.”

A year after his brother died, Peak was also shot. He recovered and moved to Huntsville where, he said, he feels safer and where this interview was conducted in mid-November.

“I chose to move from Birmingham to Huntsville for various reasons,” said Peak. “The number-one reason was that my brother’s death took a toll on me. I was just battling with a lot of things. I ended up getting shot literally a year after my brother got killed. My mom feared losing another son.”

Peak’s mother encouraged him to “find a fresh, new start.” He also remembered his pastor conducting a sermon at a church in Birmingham about “shifting,” which helped him make the decision to move.

Peak, 24, said his brother was happy, intelligent, caring, outgoing, friendly, respectful, sensitive and generous. He remembers spending a lot of time with his brother in an outbuilding in the backyard of their mother’s house in Birmingham, where Foster would often house and feed friends who had nowhere else to go.

“He would give people the shirt off his back, the shoes off his feet,” Peak said. “He loved everybody. He helped everybody. He was a protector. He protected what was his, and we were his.”

Foster liked playing basketball and football with his neighbors and hanging out with his friends, but “more than anything, he enjoyed getting his family together,” his brother remembered.

“He wanted us to be as close as possible. He wanted me to be great. He wanted me to stay in school. He wanted me to be better than who he said he was,” Peak said.

On the wall near the front door of his apartment in Huntsville, Peak has hung a vision board adorned with bold, glittered letters and a list of goals, including “Staying committed no matter the challenges thrown my way” and “Staying positive at all times.”

“The legacy that [my brother] left behind, which impacted me, impacted others, was to be strong, stand on 10 toes, and don’t let nothing knock you down, but if it knocks you down, get back up. That’s what I took from him,” Peak said.

Their mother, Wytangy Peak-Finney, often visits and upkeeps her son’s grave at Zion Memorial Gardens Cemetery. Their family takes vacations on the anniversary of Foster’s death and hosts get-togethers on his birthday, Feb. 25.

Wiping tears from his eyes as he described celebrating his brother’s birthday without him, Peak said these celebrations are special to him because he can feel his brother’s presence during the gatherings.

Peak is pursuing an online degree in mortuary science with Jefferson State Community College. He plans to become a funeral director and own a funeral home. He said his brother wanted him to do well in school.

Though Peak has moved to a different city, he thinks about his brother every day.

“Long live my brother forever. Until I see you again, I love you, I miss you, we miss you. Your name will never, never die. Love you, bro,” Peak said.

Velinda Carey

In a room dedicated to her brother in her mother’s East Birmingham house, Velinda Carey remembers life before her brother’s death.

Derrick Marks was shot and killed on Feb. 25, 2020, at the age of 25.

The walls are painted dark blue, Marks’ favorite color, and on them hang photos of Marks and a large quote about remembrance and grief: “Remembering you is easy, I do it every day. Missing you is a headache that never goes away.”

Marks was a music artist. When he told his family he wanted to be a rapper, they were surprised—they didn’t know he was musical—but supportive. “He had a lot of talents, hidden talents,” Carey said.

After Marks’ death, his family hosted an album release party in his honor, where they played his music and projected his videos on the walls.

Hanging behind Carey during the interview was a large poster of her brother’s album cover: “I hate that he couldn’t be there for [the album release party], but it was always something he wanted to do, have something big for his release. So, we just went ahead and did it for him and dedicated it to him,” she said.

Marks loved cars. His white-and-red Mustang sits in his mother’s garage. There is a ding on the front bumper. Before his death, Marks ordered new, shiny, red rims. When they arrived, their mother made sure to replace them.

“The energy my brother used to bring. He’d bring a lot of energy. He’s very smart, intelligent, all that. He’s basically the fun of the house, that’s just how he is,” Carey said. “He was always a fun person to be around.”

Carey, 33, recently underwent a kidney transplant. She said her brother wanted to donate his kidney to her but was not able to because he died before he was able.

Since the death of her brother, Carey has not sought counseling, though she thinks she needs it.

“I don’t think I’m ready for it. It’s hard to talk about it as it is,” she said. “I haven’t [coped]. I haven’t dealt with it. In my mind, it’s like I put him in another state, or he’s on vacation overseas, or he’s somewhere far away and hasn’t returned yet. I don’t want to say he’s gone and he’s not coming back. I know it’s real, but I don’t want to face that reality.”

“Sometimes I wanna scream, I wanna holler, but I can’t do that. It’s not going to bring him back,” Carey added. “It was just us. We grew up together, we did everything together. Even though it was a five-year difference, I still had all of those years with him. We fussed and fought. That was my brother.”

Since losing her son, Marks’ mother, Catrina Carey, has become a counselor and mentor to others who have lost a loved one to gun violence.

She often sends inspirational messages and Bible verses to a long list of contacts to let them know they are not alone. She advises others to help those who are struggling with grief by getting to know the resources available within their own communities, such as grief counseling and mental health programs.

“We have to stay unified to be able to come up with a solution to stop the violence,” she said. “That means being in unity with the police, the officials, organizations working together on one accord because we’re all working toward the same greater good.”

Velinda Carey said holidays have not been the same without her brother.

“We’re used to him being that person that brings the energy. When he walks in the room, he’s the loud one. He’s going to come in screaming and hollering about something. That’s what we looked forward to,” she said. “Him not being here, we don’t get that no more.”

The last holiday Velinda Carey celebrated with her brother was the Christmas before he was killed.

“With the health issue I have, I have some days when I can’t do certain things, or I can’t get my kids something. It all comes with the condition,” Velinda Carey said. “That year, he showed out, and not only for my kids—he showed out for me and my mom, too. He came with a lot of gifts for my kids.”

Velinda Carey has two sons, 16 and 7. The youngest often asks questions about Marks and what happened to him. Carey has a tattoo of her brother on her upper-right arm. She said her youngest son will often kiss the tattoo when they talk about him.

To keep Derrick Marks’ name alive, “We continue to post his videos, continue to post his music,” Velinda Carey said. “We want everything to be the same, even though he’s not here. It’s hard, but at the same time we just gotta keep going, we got to.”

The Amelia Center at Children’s of Alabama offers resources for those who are grieving; counselors for adults, teens, and children can be reached at 205-638-7481. Additional resources for families, including talking about death, methods of coping with loss, child trauma, and bereavement, can be found on the Children’s of Alabama website.