This is an opinion column.

Brown Chapel A.M.E. cannot fall. It simply can’t.

Back in May, I chronicled the heroic—and expensive—effort to restore the historic 114-year church in Selma, Alabama, where citizens battling for voting rights gathered before their marches across the Edmund Pettus Bridge on the way to Montgomery.

Original estimations put the cost of renovations at less than $2 million–$1.3 of which would be funded by a federal grant obtained in 2021. A storm soon after work began revealed unforeseen damage to critical beams weakened by termites, water, and time. Juanda Maxwell, who chairs the Historic Brown Chapel AME Church Preservation Society, charged with caring for the aging structure told me then at least $5 million more would be needed to complete repairs.

That won’t be enough. At least another million is likely needed.

“It’s a scary-sounding number,” said Jerry Lathan, co-owner of the restoration firm overseeing the project. “It’s become substantially more extensive and expensive. The good news is we’ve identified funding sources for most of that and have helped the foundation and the church present the costs and explain the need.”

Lathan said my story inspired at least one donor.

“I’m told that within two weeks, an Arizona-based well-to-do individual called and pledged a million dollars in matching dollars,” he said recently, “basically saying I’ll match every dollar you can raise up to a million.”

The project previously received $500,000 from the National Park Service and another $150,000 from the National Trust. There’s hope for another $1.5 million allocation from Congress “as a special or extraordinary need to preserve a national monument,” Lathan said.

“Probably three million of what’s necessary to finish it is pledged,” he added. “It hasn’t all gotten here, but it’s believed to be en route over the next several months. So, from a practical point of view, that means we’ve been able to continue to work almost without interruption.”

Barring no more storms—literally or figuratively.

Lathan says the goal remains to create a museum-quality restoration, a notation designated for only historically significant structures. “There was an iconic figure or event that happened there,” Lathan said. “The objective is to have it look like it did when that history happened.”

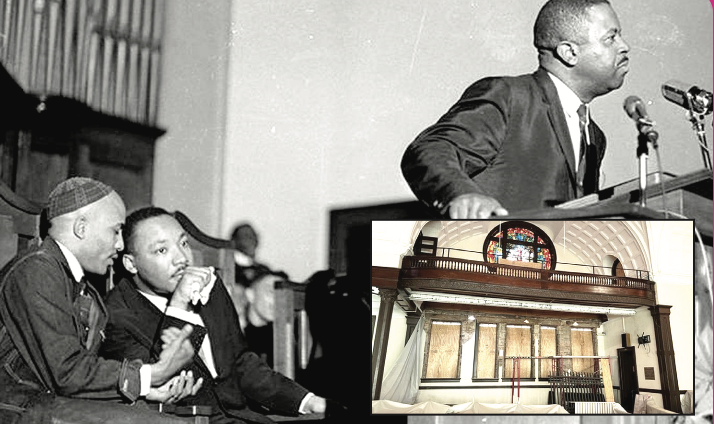

For instance, the wood accents on the now all-white ceiling were originally painted gold. The restoration will replicate that look. “We want the interior of the church to look like it did so if John Lewis or Dr. [Martin Luther] King walked in the door they would recognize everything as it looked when they left or the marches. That’s our goal, to put it back precisely in the colors, fabrics, and textures that were there at that point in time.”

Last summer, it was named the most endangered historic site in the nation by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the Washington DC-based nonprofit that tracks and seeks to preserve sites that are threatened with extinction.

“We had generously accounted for unforeseen things because we’ve just done this long enough,” Lathan said. “If you see five bad windows there’s a pretty good chance the other 18 are going to be bad. We went ahead and added for things we haven’t confirmed or seen yet. So, a couple of things have come in a little easier than we thought and some others have been dramatically worse but it’s all coming out in the wash.”