This is an opinion column.

The kid was still a kid. Yet already Reggie Jackson’s power was pure, his potential boundless—and both were evident to all.

It was 1967. Jackson was in his only season as the young power-hitting outfielder of a talent-laden Southern League team in Birmingham that was the Double-A affiliate of the Kansas City A’s.

These were horrid times in Birmingham. In Alabama. In the South. None of this is a secret. Blacks were terrorized by segregationist laws, the Ku Klux Klan, and everyday white people. No secret, either.

Sometimes, still, we must be reminded. We must see that the pain inflicted in those years still lingers in those who felt it. Even within those with power and potential.

Even in Reggie Jackson.

Now 78, Jackson, still looking fit, is grateful for each day. On Thursday afternoon, we shared a stage at Regions Field and chatted about life—then and now.

“I am grateful for my health,” he said early in our conversation. “I feel wonderful. I recognize that at my age, tomorrows not promised.”

There were smiles. Jackson talked movingly about his siblings—brother Joe, 85, was in the audience with his wife—and sister, who is 89. “It’s hard to get him out of the house,” Jackson said of his brother. “We have a long and wonderful history of his mentoring [me]. We haven’t had an argument since we were kids. When I got bigger than him, he was smart enough to talk me out of fighting.

“He helped shape me. As far as who I am today and who I was, that’s because of him.”

There were laughs, too.

There was passion, especially when Jackson spoke to the many Birmingham City School students in the room and touted his Mr. October Foundation, which supports STEM education programs and workforce development for our youth. “They are the future no matter who we’re going to be,” he said. “I want them to know they are so important to progress of the world, not just the nation or this community.”

And there was pain. You’ve likely seen the clip of Jackson, who grew up in Pennsylvania and attended Arizona State, sharing the pain of his time off the field in Birmingham with Fox Sports analysts that night prior to MLB’s Salute to the Negro League’s game between the St. Louis Cardinals and San Francisco Giants. It was not the first time that day he shared it that day.

Earlier at Regions he called some of his times with teammates “wonderful”, and credited Rollie Fingers, Joe Rudi, Dave Duncan, as well as a myriad of “white friends” in the city for helping make it so. Then he struggled, paused for several moments, to find to appropriate words to express the fullness of his time Birmingham away from Rickwood and his friends.

“The experiences I had … were difficult, awkward,” he finally said. “They were tough.”

Jackson didn’t want to come to Birmingham. Didn’t want to play in Birmingham. He grew up with white friends in a mixed neighborhood in Pennsylvania and attended Arizona State. The shock of southern evils began at spring training where the A’s had colored barracks, and Black players had to shower separately from white teammates.

“Those experiences where enlightening and frightening,” he said. “I stopped practicing and was not going to come here. My dad came down and drove me to Birmingham.”

Here, Jackson could not find a place to live, so he couch-jumped in an apartment complex where Rudy, Fingers and Duncan lived until word surfaced that he was staying there, and the south reared its ugly. “I stayed until they threatened to burn the complex down,” Jackson remembered. “We were all kids.”

He moved out and into the Bankhead Hotel downtown, where he remained mostly in his room. “I was always afraid.”

That fear still hurts. Clearly. As do the stings that were part of everyday life in the South at the time.

At the end of our conversation, we asked for questions from the audience. A man rose and recounted a few games at Rickwood when Jackson achieved magnificent feats with his bat, then asked Jackson who shared his most memorable moment.

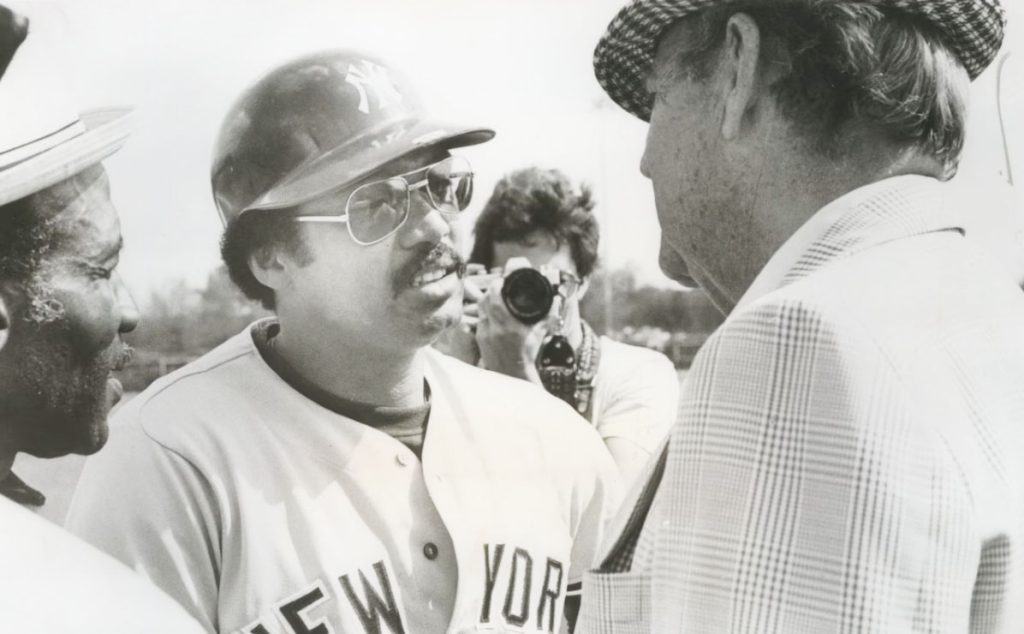

Again, Jackson paused. He began talking about a game where he hit a couple of triples and “could run like a deer.” Paul (Bear) Bryant, whose son Paul was the A’s general manager, was in the stands that day, he remembered. Jackson paused again. After the game, Jackson said the Alabama coach came into the locker room and spoke with him.

“It’s tough to hear if you’re from Alabama,” Jackson began and placed his hand on my left shoulder. “At the same time, it came from a friend. He never apologized for it but he was a friend.”

A few people were around his locker, including the Bryants, father and son.

“I was getting changed, finishing a shower and putting my shirt on,” Jackson said. “Bear Bryant walked up to me and paid me a compliment.

“He said to the group, ‘This is the just kind of n….. boy we need in order to compete with Bo [Schembelcher], Woody [Hayes], Ara [Parsegian] and Johnny [Robinson] … and Joe Paterno of Penn State.”

“He meant it as a compliment,” Jackson said. “He said, ‘If we don’t get one of them, we won’t be able to compete with them.”

Jackson said he did not respond to Bryant. “I didn’t know what to say.”

Jackson added: “I got called up to the major leagues and Bear Bryant came up to Chicago … and watched me play my first game. Twenty-one years later when I retired I played my last game in Chicago and Bear Bryant came to see me play my last game.

“That friendship lasted until he passed, but that was the most impactful thing that happened to me in Rickwood Field.”

Roy Wood, Jr. was in the room, serving as co-host for the luncheon. It had grown quiet. Later, the comedian and Birmingham native told me: “It says a lot about our country when you can ask a Black person when was a really good day in Alabama in the 60s and within their reply, they were still called the N-word.”

It wasn’t the first time Jackson told the Bryant story. Here’s this from a Sports Illustrated cover sory in May 1987 in which the Hall of Famer spoke of baseball’s racism as “a serious problem that isn’t going away”:

“It was while I was in Birmingham that I met Bear Bryant. His son was the general manager of the ball club. Bryant told me I was ‘the kind of n….. boy’ they needed to show the people in his state that we would be good athletes and be good for his school. He said it as a compliment. He said it with his arm around me. Whenever he came to New York, he always made it a point to come see me, and I enjoyed visiting with him. He meant no harm. That’s the way it was.”

More from Wood, Jr.: “Reggie Jackson’s ability to take the pain that he endured and harness it into something productive and inspiring is probably his greatest athletic feat. To overcome that emotion and trauma and still be able to focus on just playing the game of baseball—for that alone he deserves to be in the Hall of Fame. He played with anger and a ferocity in his heart. Imagine how much greater he might’ve been if he had been given the gift of love.”

Just over three years after Bryant put his hand on Jackson’s shoulder at Rickwood, on Sept. 12, 1970, USC running back Sam (Bam) Cunningham, a sophomore on his field collegiate road trip, helped crush Bryant’s all-white Tide. Cunningham rushed for 135 yards and two touchdowns in a 42-21 over Alabama at Legion Field. In Bear’s backyard. And Cunningham wasn’t even in the starting lineup that night.

There are numerous accounts of Bryant going into the USC locker room and touting Cunningham. Interestingly, this story, a feature on Cunningham (who died in 2021 at 71 years old), disputes that:

Despite what urban legend claims, Cunningham was not grandly introduced to the Alabama locker room after the game, but he did receive a polite and earnest congratulations from one of the winningest coaches in college football history. Bear Bryant met Cunningham, Jimmy Jones and Clarence Davis, USC’s all-black backfield, outside the locker room to compliment each on a game well-played, and the team set off back home to California.

Try to embrace this: Jackson did more than express anger and pain while in Birmingham this week. Indeed, he used the word “grateful” many times.

Grateful for the white friends and teammates who helped him endure Birmingham.

Grateful for other athlete/icons who inspired him—Jackie Robinson, Muhammad Ali, Jim Brown, and certainly Willie Mays (“Willie shared things with me he couldn’t say publicly,” Jackson said.)

Grateful for family.

Grateful to God. “Every day I wake up and just say, ‘thank you,’” he said at the luncheon. “‘I’m grateful for this day.’”

Near the end: “I sit here today between great sadness, tears and a good feeling about being heard,” Jackson said. “The journey—you just don’t understand [as a young person] why someone would have that kind of anger towards you for no reason. It was extremely difficult to go through as a human being. We’re all the same and you don’t know why you’re treated less than a person.

“I’m glad I got through it, but not glad I went through it,” he said. “No one in this room would want to. I don’t wish it on anyone.”