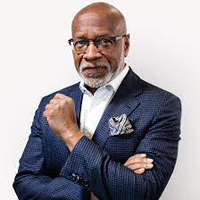

By Roy S. Johnson, member, National Association of Black Journalists Hall of Fame, Edward R. Murrow Award winner, and a Pulitzer Prize finalist for commentary.

This is an opinion column.

They’re almost gone now, but they were there.

Their voices are being heard, and their presence acknowledged. Finally. They were there.

Their pain, their fears, their nightmares were real because they were there.

Today, as we do each year on this somber day, we honor those men among the thousands who bravely stormed the beaches of Normandy, France on June 6, 1944, at the onset of Operation Overlord. The near-three-month World War II campaign under Gen. (and future President) Dwight D. Eisenhower culminated in the liberation of France and the defeat of Nazi Germany.

D-Day is what we call it now. Or what the military called it.

I long wondered what the D stood for. Maybe for Deadly or Death, in recognition of the staggering 2,501 Americans (almost 4,500 overall), young men gunned down in the hail/hell storm of German fire that day. Young men still buried on those shores.

Maybe Determination—for the men who soldiered on not knowing if they would see another sunrise.

Maybe Devastation—for the families left behind whose days were always darkened with grief for the loved one who never returned.

Or simply, maybe for Damn.

Damn that we left not just men behind but also the truth about all who were there. All who stormed on that day, and the days beyond. All who endured the pain, the fear, and the nightmares.

The military was still then segregated on that day—still infected with the myth of inferiority that Jim Crow injected into America.

The myth that Black Americans were not good enough. Not good enough to sit alongside whites on the bus. To eat at the same lunch counter. To learn in the same classroom.

Not even good enough to die. Not with a gun. Not on the front lines.

Black soldiers were drafted and volunteered by the thousands yet were not deemed good enough to fight on the front lines. Only good enough for service roles— vital service roles, to be sure.

On that day, though, the all-Black 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion was there. Never heard of them? I had not either. They charged the beach to protect the white soldiers on D-Day as life and death from German guns sprayed upon the shores, indiscriminate of skin color.

You won’t see those Black soldiers chronicled in movies that pay homage to the deadly day (see: Saving Private RyanNot even Tom Hanks knew they were there.) or in the pages of most history books.

Still, they were there.

Robert Coleman “R.C.” Adams was there. The Huntsville resident hit Normandy three days after D-Day as part of an all-Black unit assigned to gather and bury the body that lay strewn on the beach. Bury them in what was now Normandy American Cemetery. He lived to be 104 before passing in 2018.

Robert Brown was there. The son of sharecroppers who grew up as one of 10 siblings in Mantua, he was originally assigned to assigned to the 389th Combat Engineer Regiment, which mainly deactivated landmines. He once shared haunting remembrances of D-Day for the World War II Museum in New Orleans:

We went in on LSTs (Landing Ship, Tanks) – the tide was lower than expected and boats would get caught up on three pronged spikes, and there was wire…I can see that gate open on the boat…when it opened, some of them didn’t come out. The Germans had machine guns aimed into those boats. When we go out the water was up to here! – pointing to his neck! The Germans had been there so long they were dug in with hydraulic lifts from bunkers.” He further added, “When we got to the hedges—If we advanced 100 or 200 yards a day it was good. It was like a checkerboard where the French grew grapes. There were human bodies – bloated – everywhere – we couldn’t pick them up.”

After Normandy, Brown was part of the 761st “Black Panther” Tank Battalion—the first Black Panthers. He returned home and became the first Black school superintendent in Greene County, Alabama.

Others were there, too. Like James C. Knowles, a Mississippian who later lived in Jefferson County. Like James Stephenson, a Tuscaloosa native who was part of the 463rd Amphibious Truck Company, one of three all-Black companies who were there that day, who drove the soldiers to the beach.

All of them were good enough—as were the thousands of Black soldiers who risked their lives in Normandy.

This week, many among the last of the WWII vets ventured back. Back to Normandy to commemorate 80 years since that day. Including Enoch “Woody” Woodhouse, a Boston native who was a member of the famed Tuskegee Airman.

Last weekend, I watched a short (45 minutes) doc called A Distant Shore: African Americans on D-Day. The pain of that day, the pain of being deemed not good enough, the pain of what they saw, was in their faces. In their voices.

On this day, honor those men by giving it your time (It’s on Hulu.)

They were good enough to earn it.