This is an opinion column.

No one owns the seat. It’s easy to forget that when it’s been yours for so long.

Yours, as in, entrusted to you by the people. Entrusted to you by the voters. Entrusted to you with the understanding that every time you settle into it, every time you take any action from it, every time you claim the title and wield the power it represents, you will do so knowing that you represent them.

The people. The voters.

John Rogers isn’t the first politician to have maybe gotten a bit too settled in. To have situated himself into the seat so long its contours were reshaped to his own. So long to have believed there was a deed to the seat with his name on it, affording all the rights, privileges, and entitlements of ownership.

Legal or otherwise.

He won’t be the last, either.

Because it’s easy, so easy to forget.

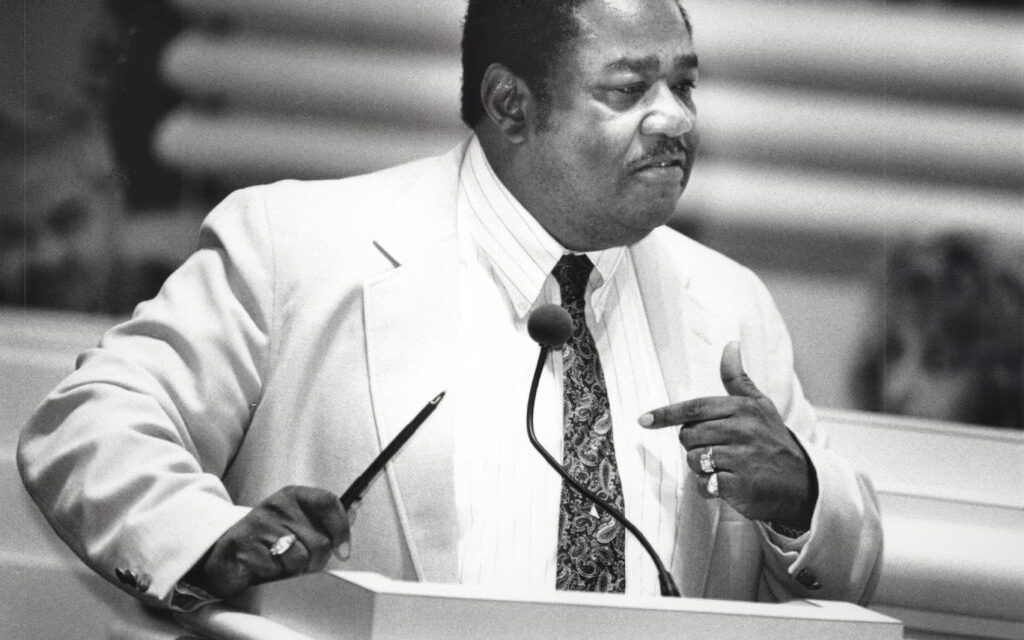

John Rogers, 83 years old, may go to prison because, according to a revelatory plea agreement he signed, the long, long, long, long time state House member, representing District 52—which stretches west bumping into Fairfield and Midfield through Birmingham, ballooning along Oxmoor Road and swallowing the Zoo and Botanical Gardens tickling Mountain Brook—forgot.

Forgot he represented the people living within those twisting boundaries. Forgot he didn’t own the seat.

Rogers agreed to plead guilty to a count of conspiracy to commit mail and wire fraud and a count of conspiracy to obstruct justice. He agreed to return $200,000, restitution for directing twice that amount to a pet non-profit (Piper Davis Youth Baseball League) run by another public official who forgot he didn’t own the seat entrusted to him by the people, by the voters: Fred Plump. Now former Rep. Fred Plump.

Rogers then, the agreement reads, finagled such that the $200,000 flowed back to him, through his girlfriend/ex-girlfriend/personal assistant Varrie Johnson Kindall.

Oh, as really an aside because it’ll make you wonder how such a minuscule amount of money can make you forget, Rogers and Kindall also conspired, which was confessed in the agreement, to receive $1,800 —one thousand eight hundred dollars—as an “administrative fee” from the founder of an anonymous (but not) organization to which he directed $10,000 of our money. Rogers previously outed the founder as George Stewart, leader of the American Gospel Quartet Convention.

Oh, and oh, Rogers asked Kindall to impale herself on a sword for him. He asked her to accept “full responsibility” for any crimes he might later be accused of committing. It’s all in the agreement. In exchange, he’d “pay Kindall’s mortgage and take care of her children if Kindall went to jail.”

Oh, the depths of what you can do—or believe you can do when you forget. Forget you don’t own the seat.

I was just into my second job out of college when Rogers became a freshman member of the Alabama House in 1982. I’ve held seven full-time and numerous side-hustle gigs since then. Three times, I was laid off.

I didn’t own those seats, either.

Last September when a flotilla of federal grand jury indictments was announced against Rogers he characteristically, boldly, and emphatically denied all.

“I wouldn’t do anything that crazy,” he said what now seems way back then. “I wouldn’t do anything that stupid. This is going to be a royal affair. I’ll enjoy kicking their ass.”

A lot of folks are sad today, feeling kicked in the stomach today because Rogers undeniably did some good while in the seat.

In an age long ago when Democrats actually held sway in the Alabama legislature, he ably served as chair of several House committees and ruled the Jefferson County legislative delegation.

He was a bombastic defender of those he represented, of those who entrusted him to do so—even as he also ducked, dodged, and deflected varied charges aimed towards him.

A lot of folks are sad today because they must finally accept what they long denied—that for who knows how long now, Rogers thought the seat was his, not theirs.

In exchange for signing the agreement, the feds will drop 18 other charges against Rogers once a federal judge accepts and signs it.

Immediately upon, Rogers will stand up and stand down. He will abandon, after more than four decades, the seat—the one he forgot he never owned.