This is an opinion column.

Birmingham-Southern is going to get its money—so, it seems. Its $30 million lifeline. Or care package.

Its persistent and insistent benefactors in Montgomery and Birmingham appear all but certain to ensure the debt-laden college on the hill gets its chance to dig out of the hole it dug and once again be the beacon of light its friends and neighbors boast it to be.

I’ve been pretty clear on my stance against utilizing public taxpayer funds to bail out the private educational institution. That said: After BSC deposits its bounty, I hope it succeeds.

I truly do.

I hope it takes the $30 million loan it’s now likely to receive from the state, along with the $5 million loan it will receive from Birmingham taxpayers (half of it will be forgiven if BSC opens for classes this fall), and does everything it says it will do.

I hope its thriving alumni will transform their financial commitments to cash, fulfilling the millions in pledges they’ve sat on since well before December 2022 when I reported the place was in dire distress.

That BSC will once again be a welcoming bastion of liberal arts education for young people throughout the nation and be (finally) more welcoming to young graduates of Birmingham City Schools—and be more culturally reflective of the city in which it resides.

I hope all that happens. I truly do.

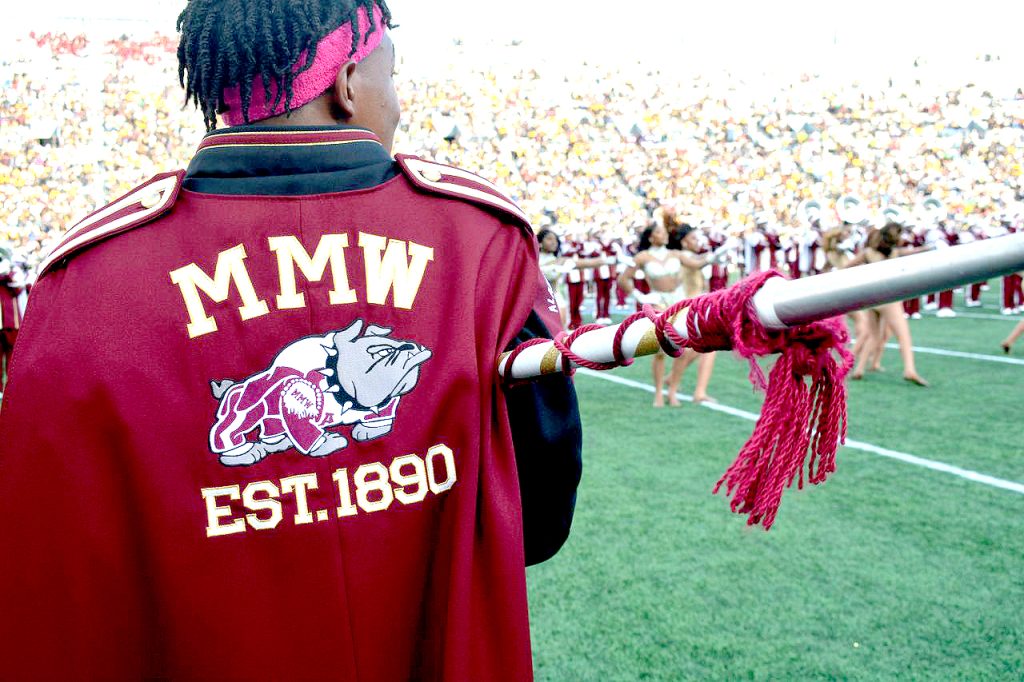

I truly hope this, too: That state lawmakers will be as assiduous about paying Alabama A&M in Huntsville some of the $527 million Alabama owes the historically Black public land-grant institution.

Last September, federal officials dropped a late payment notice on Gov. Kay Ivey. The letter, signed by the U.S. Education Secretary Miguel Cardoza and U.S. Agriculture Secretary Thomas Vilsack, explains the convolutedness of the historical commitment by states to equitably fund their Black land-grant institutions on the same level as white land grants. And why the funding is vital.

Land grants are colleges built between 1862 and 1890 with grants from the federal government, which aimed to help working-class Americans gain access to higher education. Alabama has three land grants: Auburn University, Tuskegee University, and A&M.

“While HBCUs, including 1890 land-grant institutions, represent 3 percent of postsecondary institutions, they enroll about 10 percent of all Black college students,” the secretaries wrote. “Furthermore, these institutions generate close to $15 billion in economic impact and over 134,000 jobs annually in the local and regional economies they serve.”

The letter mentions only A&M, whose underfunding was determined by an analysis of funding between 1987 and 2020 and tabulated to be $527,280,064. That’s more than half a billion dollars it was supposed to provide to the institution.

Not money it is begging for to overcome its ill-spending.

“Alabama A&M University, the 1890 land-grant institution in your state, while producing extraordinary graduates that contribute greatly to the state’s economy and the fabric of our nation, has not been able to advance in ways that are on par with Auburn University, the original Morrill Act of 1862 land-grant institution in your state, in large part due to unbalanced funding,” the letter notes. “These funds could have supported infrastructure and student services and would have better positioned the university to compete for research grants.

“Alabama A&M University has been able to make remarkable strides and would be much stronger and better positioned to serve its students, your state, and the nation if made whole with respect to this funding gap. … [It] is our hope that we can work together to start a dialogue and develop a plan of action to make this institution whole after decades of being underfunded.”

Alas, Ivey penciled in $57 million for the institution in her proposed budget to lawmakers, about a $4 million bump over 2022.

At that rate, the state’s overdue balance to A&M will be caught up in, oh, about 132 years.

Last fall, A&M enrolled its largest freshman class: over 2,600 students, a 10% overall jump in enrollment. Overall, it enrolls 6,657 students.

To keep BSC afloat, state lawmakers are essentially giving themselves a mulligan. Last year they tried to save it with the Distressed Institutions of Higher Education Revolving Loan Program, administered by Alabama State Treasurer Young Boozer. But Boozer balked, citing a lack of confidence in the institution’s collateral and restructuring plan.

Now comes SB31, authored by Sen. Jabo Waggoner (R-Vestavia Hills) and co-sponsored by 20 other state senators. If passed, will yank authority from Boozer and handed to the Executive Director of the Alabama Commission on Higher Education and a state-regulated bank, which must review and sign off on the institution’s collateral and restructuring plan.

Until the state satisfactorily addresses A&M egregious funding gap, BSC shouldn’t get a nickel, frankly.

That said, I do hope BSC gets its chance to rise from its still-smoldering ashes. I truly do.

The state budget has yet to be finalized and A&M’s allocation could shift. I hope it does. I truly do.