By Stacy M. Brown,

NNPA Newswire

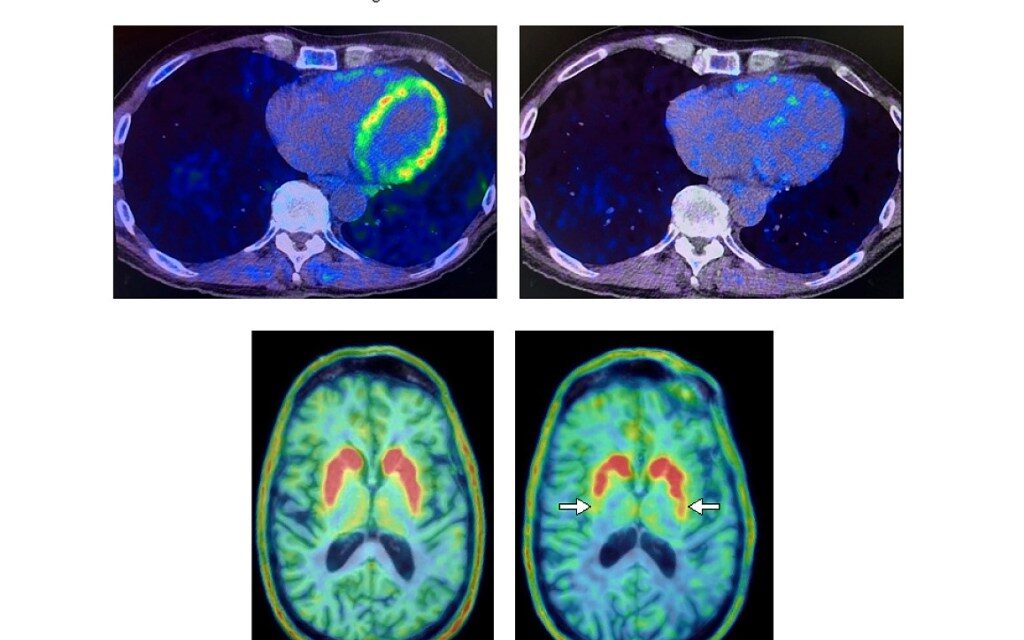

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has released a major study showing how positron emission tomography (PET) scans of the heart could be used to find people likely to get Parkinson’s disease or Lewy body dementia. Health officials said the research, the brainchild of specialists from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), marks a significant advancement in the early detection of these crippling neurodegenerative disorders.

This discovery, led by scientists from the NINDS and published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, could change how early these crippling neurodegenerative conditions are found.

In the pioneering investigation, scientists delved into neurotransmitter levels by employing PET scans on the hearts of 34 individuals with known Parkinson’s disease risk factors. The scans gave new information about the people who later were diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease or Lewy body dementia. Lewy bodies—abnormal alpha-synuclein protein deposits—are the root cause of both conditions.

The research took place at the NIH Clinical Center; currently the sole facility offering 18F-dopamine PET scanning. PET scans employ a radioactive tracer to visualize metabolic or biochemical processes within body organs.

Norepinephrine, derived from dopamine, is notably deficient in the brains of people living with Parkinson’s, health officials explained in the study. Dr. David S. Goldstein, the principal investigator for NINDS, has previously shown that people with Lewy body diseases have very little cardiac norepinephrine. He explained that nerves that supply the heart typically release this neurotransmitter.

The new study, led by Dr. Goldstein, found that people who were at risk and had low 18F-dopamine-derived radioactivity in the heart were much more likely to develop Parkinson’s or Lewy body dementia over time than people who had the same risk factors but normal radioactivity.

“Imagine the scans are frames of a movie. The frame at 8 minutes during the first evaluation is already enough to identify the people who are likely to go on to develop a central Lewy body disease years later,” Goldstein stated.

For the research, 34 individuals at risk for Parkinson’s were engaged, and subjected to cardiac 18F-dopamine PET scans every 18 months for up to approximately 7.5 years or until diagnosis. Those who took part had at least three things that put them at risk for Parkinson’s – a family history of the disease, anosmia (loss of smell), dream enactment behavior (a sleep disorder), and orthostatic intolerance symptoms, like feeling dizzy when standing up.

Eight of the nine participants who had lower cardiac 18F-dopamine-derived radioactivity on their first scan were later diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease or Lewy body dementia. Remarkably, only one of the eleven participants with normal initial radioactivity developed a central Lewy body disease. All nine participants who developed a Lewy body disease exhibited low radioactivity before or at the time of diagnosis.

Researchers noted that the study supported the idea that synuclein disorders, including Parkinson’s disease and Lewy body dementia, affect the nerves that control automatic body functions like blood pressure and heart rate. Officials said Goldstein’s extensive work, among others, showcases synuclein aggregation in nerves related to gastrointestinal organs, skin, and glands in both conditions.

“We think that in many cases of Parkinson’s and dementia with Lewy bodies, the disease processes don’t actually begin in the brain,” Goldstein remarked. “Through autonomic abnormalities, the processes eventually make their way to the brain. The loss of norepinephrine in the heart predicts and precedes the loss of dopamine in the brain in Lewy body diseases.”

Health officials declared that finding biomarkers for diseases before they show symptoms, in the “preclinical period,” is very important for testing that can help with early intervention. Parkinson’s motor symptoms do not show up until dopamine-producing neurons in parts of the brain that control movement are severely damaged or lost.

“Once symptoms begin, most of the damage has already been done,” Goldstein emphasized. “You want to be able to detect the disease early on. If you could salvage the dopamine terminals that are sick but not yet dead, then you might be able to prolong the time before the person shows symptoms.”

The study concluded, “Using PET scans to find people with preclinical Lewy body diseases could lead to testing preventative measures like changing your lifestyle, taking dietary supplements, or taking medicine.”

This article was originally published by NNPA Newswire.

The post Revolutionary study explores use of unique heart scans for early detection of dementia disorders appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers .