By Megan Sayles

AFRO Staff Writer

msayles@afro.com

Back in the 1960s, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) developed Freedom Schools to teach reading, writing, math, civics and history to African Americans whose self-determination was inhibited by the legacy of sharecropper education. The institutions’ curriculum was divided into two parts: the “Citizenship Curriculum” and “Guide to Negro History.”

The schools functioned not only as a means of delivering a quality education to disenfranchised Black communities but also as a way of preparing them to be politically-engaged citizens.

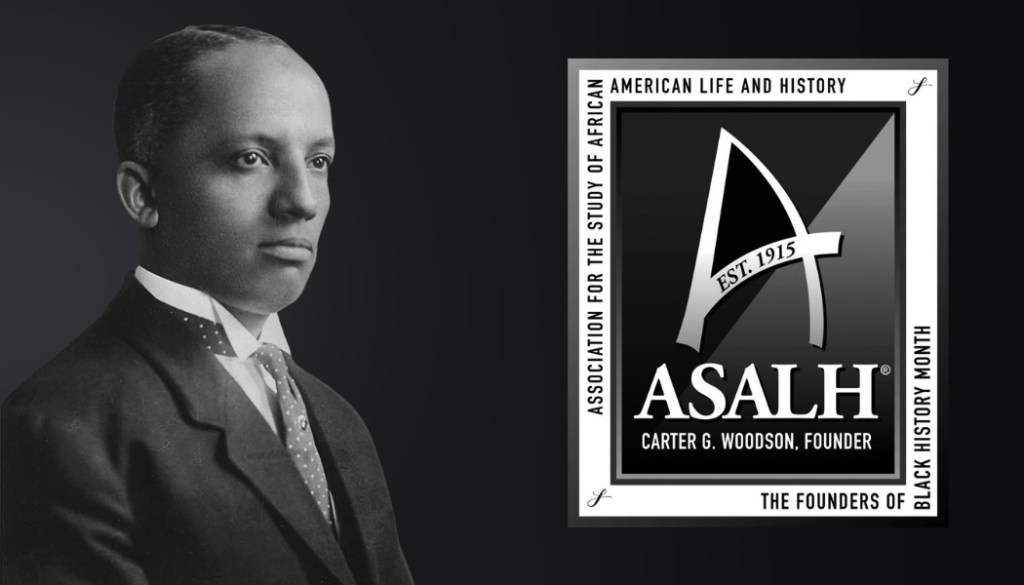

Now, in the face of attempts to restrict and censor the teaching of Black history in public schools, the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) has reinvigorated the concept.

“In the period that I started pushing for Freedom Schools, it was very apparent that Trump’s move would be to curtail our involvement and participation in public life. It was clear that they were coming after what they referred to as ‘critical race theory’ and what I simply interpret as Black historical knowledge in general,” said Sundiata Cha-Jua, an African-American studies professor and member of ASALH’s executive council. “I thought the best way for us to contest that was to return to some of the ideas of Dr. Carter G. Woodson.”

Woodson is the founder of ASALH and the creator of Negro History Week, which later became Black History Month. Cha-Jua explained the observation was an effort to promote the mass study of Black history in social institutions that Black people controlled, like churches, associations and clubs. This ensured that history could not be erased or ignored.

In recent years, states across the country have used legislation to limit how Black history is taught in public schools. They’ve primarily taken issue with the teaching of critical race theory (CRT), an academic framework that examines how racism is embedded in the country’s policies and systems rather than solely a result of individual prejudice.

Lawmakers who oppose CRT argue it can cause division between students of different races. Cha-Jua, however, sees it as an opportunity to transform students for the better. He recalled that his first encounter with Black history was reading “Before the Mayflower: A History of Black America,” by Lerone Bennett Jr. in the ninth grade.

“It was transformative. Suddenly, you’re not just the Black kid who is ridiculed by teachers and White students. You see that Africa had vast civilizations. You find out that Black people not only contributed but produced the U.S. through their labor, inventions, statesmanship and serving in the military,” said Cha-Jua. “You find out that we have been an integral part of this society and that we have most-often sought to make this society better for everyone.”

ASALH’s pilot of Freedom Schools launched in a few Florida communities during the summer of 2023. The program has since spread to the Champaign-Urbana area in Illinois and Dallas.

The organization has been intentional about placing the schools in areas where sweeping book bans have been implemented. But, it plans to expand them.

“With the Freedom Schools creating these spaces for the free-flow share of information about the Black community, we envision them being able to move across the country,” said Karsonya “Kaye” Wise Whitehead, president of ASALH. “This is not something that should just happen in states where there is an intentional banning of books. We know that if they’re banning books in Texas, it won’t take long before it hits other states.”

Freedom Schools’ curriculum covers African civilizations; the African-American experience in slavery and during the Civil War, Reconstruction era and Harlem Renaissance; the Civil Rights Movement; Black contributions to the arts; Black politics; and race relations in America.

Cha-Jua said the Freedom Schools were designed with an emphasis on middle and high school students. Through the pilot, ASALH learned that parents, guardians and grandparents wanted to participate too.

“We’re teaching the accomplishments and the strategies and tactics that we have used in previous eras to confront the challenges, oppression and distortions that we have encountered,” said Cha-Jua. “We’re teaching a history that not only looks back. We’re teaching a forward-looking history in which we have useful information that helps us understand the present and chart a path to the future.”

The future of democracy rests in understanding the country’s history, according to Whitehead. She explained that Black history can be taught anywhere, whether churches, barbershops or community centers. But, it must be taught.

“We know now more than ever that the teaching of history is important,” said Whitehead. “It is a prioritization for our organization to make sure that Black is history is being centered, uplifted and taught in as many places as possible.”

The post Reviving Freedom Schools: ASALH’s fight to counter book bans and censored history appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers.