The redrawing of the state’s districts follows a June decision by the Supreme Court in which the state’s congressional map that was drawn to reflect 2020 census results was found to dilute the voting power of the state’s Black residents. (FILE)

” data-medium-file=”https://www.birminghamtimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/VotingMap-1-1-1-300×199.png” data-large-file=”https://www.birminghamtimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/VotingMap-1-1-1.png” />

BY MARK SHERMAN

Associated Press

A three-judge panel has scheduled a hearing next week on three proposed plans would alter the boundaries of Congressional District 2 so that Black voters comprise between 48.5 percent and 50.1 percent of the voting-age population, a shift that could put the seat in Democratic hands.

The three-judge panel has tentatively scheduled an Oct. 3 hearing on the proposed plans.

By contrast, the district drafted by GOP lawmakers and unanimously rejected by the three judges had a Black voting-age population of 39.9 percent, meaning it would continue to elect mostly white Republicans, according to data simulations run by those challenging the Republican plan.

The Supreme Court on Tuesday allowed the drawing of a new Alabama congressional map with greater representation for Black voters to proceed. The justices, without any noted dissent, rejected the state’s plea to retain Republican-drawn lines that were turned down by a lower court.

In refusing to intervene, the high court allowed a court-appointed special master’s work to continue. On Monday, he submitted three proposals that would create a second congressional district where Black voters comprise a majority of the voting age population or close to it.

The redrawing of the state’s districts follows a June decision by the Supreme Court in which the state’s congressional map that was drawn to reflect 2020 census results was found to dilute the voting power of the state’s Black residents. The map, which was used in the 2022 midterm elections, had just one majority Black district out of seven seats in a state where Black residents make up more than a quarter of the population.

“This is a victory for all Americans, particularly voters of color, who have fought tirelessly for equal representation as citizens of this nation,” former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder, chairman of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, said of the decision.

Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall struck a defiant pose even as he acknowledged a court-drawn map will be “imposed” on the state for use in next year’s elections.

“There should be nothing more offensive to the people of our great state than to be sidelined in 2023 by a view of Alabama that is stuck in 1963,” Marshall, a Republican, said in a lengthy statement. “This racial agenda is pressed by left-wing activists, not just in Alabama, but in any Republican state where it might advantage Democrats.”

A second district with a Democratic-leaning Black majority could send another Democrat to Congress at a time when Republicans hold a razor-thin majority in the House of Representatives. Federal lawsuits over state and congressional districts also are pending in Georgia, Louisiana and Texas.

Stark racial divisions characterize voting in Alabama. Black voters overwhelmingly favor Democratic candidates, and white voters prefer Republicans.

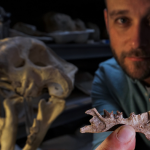

The lead plaintiff in the redistricting case, Evan Milligan, called Tuesday’s ruling a “victory for all Alabamians” and said it puts the state closer to a map that provides fair representation. “It’s definitely a really positive step,” Milligan said in a telephone interview.

The judges said Alabama lawmakers deliberately defied their directive to create a second district where Black voters could influence or determine the outcome.

Milligan and other Black voters had argued Alabama’s rearranged congressional map still meant that candidates preferred by Black voters had no chance of winning outside a single congressional district, now represented by Rep. Terri Sewell, the only Democrat and the only Black member of Alabama’s congressional delegation.

“It basically said if you were Black in Alabama, your vote would count for less,” Milligan said. “It was our duty and honor to challenge that.”

The state had wanted to use the newly drawn districts while it appeals the lower-court ruling to the Supreme Court.

Though Alabama lost its case in June by a 5-4 vote, the state leaned heavily on its hope of persuading one member of that slim majority, Justice Brett Kavanaugh, to essentially switch his vote.

The state’s court filing repeatedly cited a separate opinion Kavanaugh wrote in June that suggested he could be open to the state’s arguments in the right case. Kavanaugh, borrowing from Justice Clarence Thomas’ dissenting opinion, wrote that even if race-based redistricting was allowed under the Voting Rights Act for a period of time, “the authority to conduct race-based redistricting cannot extend indefinitely into the future.”

___

Associated Press writer Kim Chandler contributed to this report from Montgomery, Alabama.