By Brian Blum

Future blood infusions may not rely on donors.

Consider: A horrendous mass casualty event results in dozens of people injured. Many need blood transfusions. The local blood banks can’t cope with the sudden demand. Even worse, some victims have rare blood types that are not well stocked in the blood bank’s inventory.

Israeli startup RedC Biotech has a radical solution: generating an unlimited supply of universal red blood cells from a single donation of human stem cells.

RedC Biotech’s goal, says RedC Biotech CEO Ari Gargir, “is to allow the blood donation agencies to be independent of the need for donors.”

Though bringing the product to market isn’t likely to take place until the end of this decade, Gargir’s ambitious plans call for such blood to be produced and sold like any other pharmaceutical product.

The need is clear.

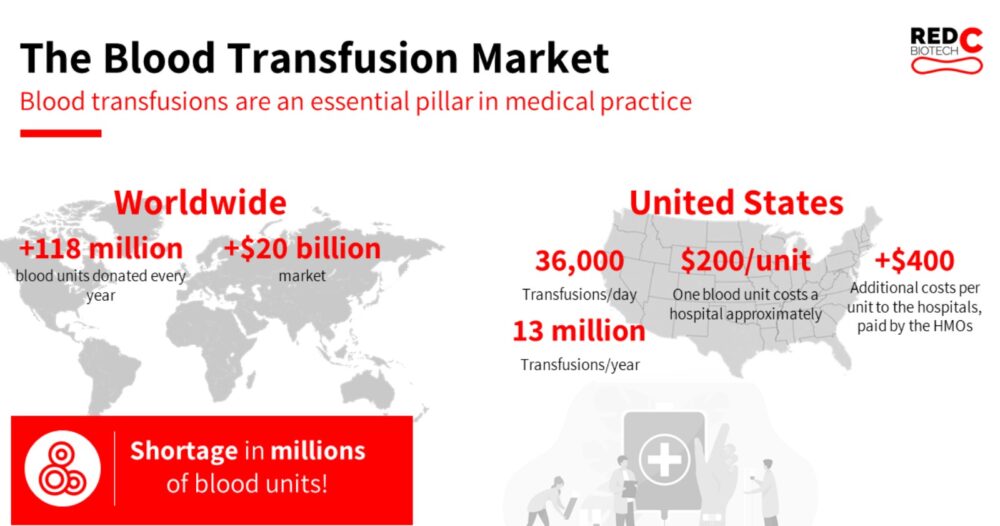

While around 120 million blood donations are given every year worldwide, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates there is a shortage of up to 100 million units, mostly in low-income countries and regions.

COVID-19 exacerbated that shortfall, as individuals have been fearful of giving blood during the pandemic. One reason hospitals have been canceling elective surgeries is because they must reserve their limited blood supply for childbirth, accidents and chronic illnesses.

Donated blood is also expensive. The average U.S. hospital pays about $200 per blood transfusion, and that does not include staffing and infrastructure expenses involved in transfusions.

“If you have a hip replacement, you may need two to five blood transfusions for up to $4,000 worth of blood [$1,000 for the blood units themselves and $3,000 for testing and equipment]. Cancer treatments require up to five blood units,” Gargir said.

Liver transplants require up to 100 blood transfusions. Some people require red blood cell transfusions on a regular basis, such as those with sickle cell disease or thalassemia.

In the United States, 36,000 blood transfusions are performed every day, adding up to some 13 million a year.

Moreover, WHO data reveals that up to 2 million people die every year as a result of blood loss from violence or injury. Some 200,000 women die in childbirth from blood loss, while 300,000 babies are born every year with blood disorders requiring transfusions, Gargir said.

Creating blood in a lab

The need for red blood cells is not theoretical for Gargir.

In 1990, he was paragliding in the Golan Heights when his vehicle crashed. “I woke up in the helicopter getting a blood transfusion,” he recalls. “This was when AIDS was still new, and I was quite scared the blood wasn’t tested.”

Gargir is a 20-year veteran of the biotech industry. With a Ph.D. in microbiology and immunology, he has held leadership positions at Israeli firms Neuroderm, Nucleix, Life Technologies and Glycominds.

RedC Biotech aims to produce “universal blood, very high quality and very clean, that can compete with the costs of the blood donation agencies,” Gargir says.

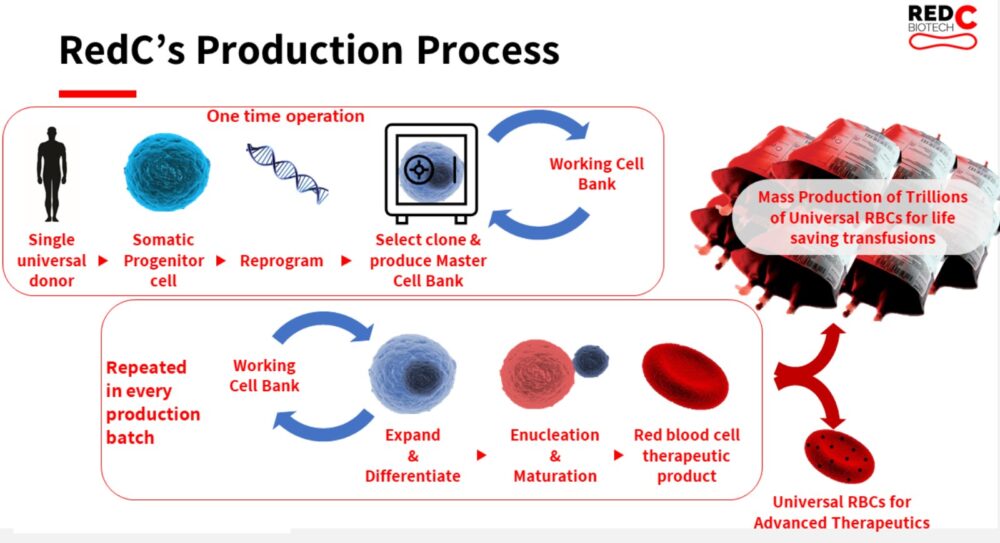

Similar to the technology used by cultured meat startups to turn single animal cells into steak and chicken, RedC’s process would start with a stem cell donation from a single “universal donor” with a special variant of the blood type O negative, which is suitable for most people.

Since stem cells can multiply continuously and differentiate into any kind of cell, they can be reprogrammed to create a master cell bank.

Samples from the master cell bank are used to grow batches of universal red blood cells in a bioreactor for about a month. The harvested and cleaned mature cells would be shipped to hospitals, the company’s target clients.

Creating blood cells in a lab means uniform quality without pathogens, viruses and other undesirable elements. And the blood can be produced according to demand and forecast.

“If you have the holidays coming up, a prediction of bad weather or even a pandemic, you can plan the amount of blood you’ll need without being dependent on donors,” Gargir says.

Several years down the road

Will blood banks go for such a big change? To find out, Gargir said he talked with more than 25 managers of blood agencies, from the American Red Cross to those in Africa and Israel.

“They have two main concerns,” he said. “First, the safety and quality of the blood and, second, the cost. If we meet the quality and the cost is competitive, they’ll be happy to do it, because it’s a pain in the neck to run after donors all day long. Most of their budget and logistics goes into finding donors, signing them up, testing each blood unit for pathogens, and then determining the blood type.”

However, RedC Biotech’s blood-as-a-pharmaceutical won’t be ready for mass marketing until the second half of the 2020s, Gargir said.

Clinical trials, starting only in the next three years or so, will last a year or two. Then the regulatory approval process can take time.

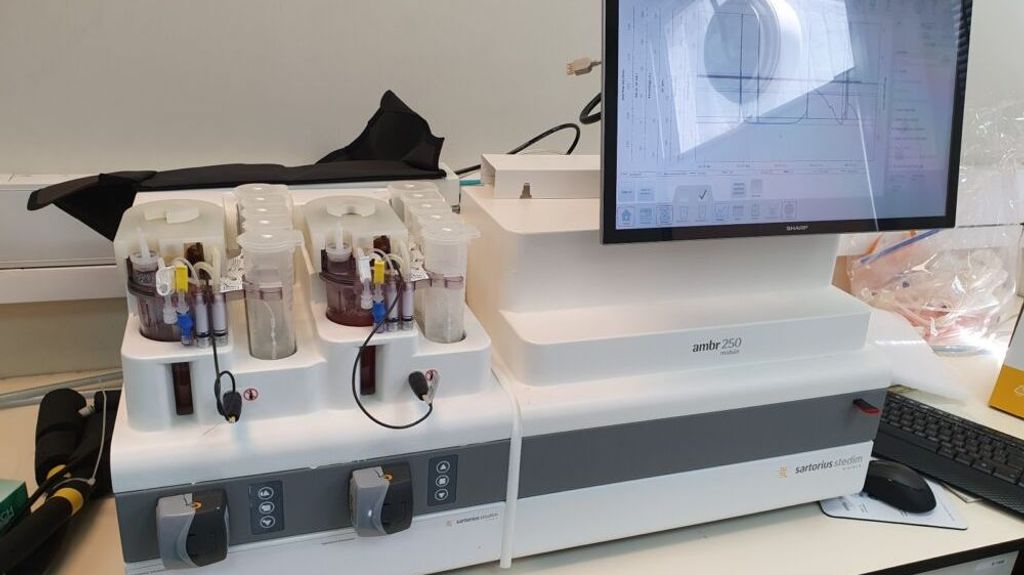

For now, the company has a proof-of-concept and is scaling up production to work with different sized bioreactors. The aim is to expand to 10 liter (2.6 gallon) reactors by the end of 2022.

Getting to commercialization will require a lot of money.

Gargir has raised about $1.4 million to date and has embarked on a new fundraising round. Much of that will go into building production facilities close to its markets. “We want to shorten the supply chain, so we’ll need to produce blood in several dozens of factories around the world.”

Logistics between the different manufacturing sites will ensure that, if there is a surplus in one area and a catastrophe in another, “we can easily move production from one place to another,” Gargir says. “Today, blood is not able to be transferred between countries, but that will change when it becomes a pharma product.”

Who will build and own the factories? It might be RedC Biotech or a partner. “It’s too early to determine the exact business model,” Gargir said. “At this point, there are no facilities capable of doing this.”

Scaling up

RedC Biotech has one main competitor, Paris-based EryPharm, which Gargir describes as “slightly more advanced than us.”

Many attempts to create synthetic blood failed in the past, probably because until recently, the technology to mass produce stem cells didn’t exist.

RedC Biotech licensed the technology to mass produce stem cells exclusively for red blood cells from Accellta, another Israeli startup. That company is also working as a subcontractor for RedC Biotech to scale up the process ahead of clinical trials.

Today, it costs RedC Biotech about $5,000 to produce a unit of blood. Gargir believes that will drop to $50 a unit in 10 years. If RedC Biotech can sell those units for even today’s market price of $200 a unit, that’s ample profit.

Gargir believes RedC’s blood cells will be suitable for 99 percent of humanity. “There will always be some unique people that need a special blood donation,” he says.

Future possibilities include using lab-made red blood cells as a platform to deliver drugs, Gargir says. “You can load therapeutic agents into the red blood cell or coat the red blood cell. They can float in the bloodstream for over 100 days without being rejected by the body.”

“This is a very large, moonshot project,” Gargir says. “But it can be done. The market potential is very high.”

Produced in association with ISRAEL21c.

Recommended from our partners

The post RedC Biotech Seeks To Make Blood Donations A Thing Of The Past appeared first on Zenger News.