By Deborah Jeon

“The past refuses to lie down quietly,” Archbishop Desmond Tutu famously said of the process of racial reconciliation in South Africa following the dismantling of apartheid.

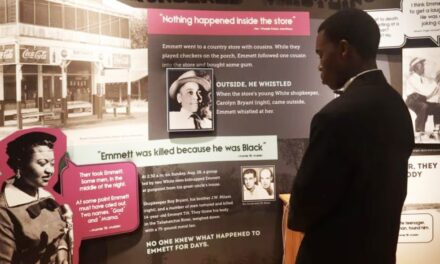

Photo: Courtesy photo

Renowned civil rights lawyer Sherrilyn Ifill echoes this sentiment in describing the shadow of past racial violence haunting Maryland’s Eastern Shore:

“The terror visited upon African American communities … lives in the deep wells of distrust between Blacks and Whites in the sense that Blacks still must keep their place and that both Blacks and Whites must remain silent about this history of lynching.” In Wicomico County, site of one horrific lynching chronicled by Professor Ifill, the system of racial subjugation endures through an election plan that makes the votes of Black residents count less than those of their White neighbors.

Challenges to all-White political rule on the Eastern Shore began in the 1980s, when ACLU lawyer Chris Brown and civil rights leader Carl Snowden first engaged with Black voters to pursue a series of Voting Rights Act lawsuits. As a young sidekick to Brown and Snowden, my ACLU career was indelibly inspired by the extraordinary courage I witnessed in Black trailblazers who took on systematic disenfranchisement of Black voters across the Shore. These heroes of yesteryear – Honiss Cane, Fannie Birckhead, James Purnell and Billy Gene Jackson, among others – sparked transformative change that opened doors to Black representation in many Shore communities for the first time ever.

Now, more than three decades after those historic advances, the struggle to overcome racial oppression continues anew amid the Shore’s increasing racial diversification. In the Town of Federalsburg and in Wicomico County, Black voters aligning with the NAACP and Caucus of African American Leaders are rising up to tackle unfinished work of that earlier era.

Discriminatory election structures enable the White majority to dilute votes and silence the voices of Black residents despite – or perhaps because of – their growing numbers. Voting patterns throughout the Shore are strongly polarized by race, meaning election preferences of Black and White voters consistently differ. And in general, White voters favor White candidates and oppose candidates of color, preventing Black candidates from attaining political office.

In Wicomico County, BIPOC residents make up 42 percent of the population, and a clear majority – 62 percent – of children in public schools. But because the election structure combines at-large and district components in a seven-member system, Black candidates are limited to just one majority-Black district in both County Council and School Board elections. Limiting such a large BIPOC population to a single representative is not only unacceptable, but blatantly illegal.

Veteran activist Mary Ashanti, who came of age amid stark segregation and racism in Wicomico County, sees this as a calculated means of suppressing Black voices. She says it operates “just as it was designed to – keeping Black people in their place, confined to their one lonely opportunity” notwithstanding Black population growth.

Consequences of this lack of fair representation are “profound,” says Wicomico NAACP President Monica Brooks. The effects include Black schoolchildren taunted by White classmates with racial slurs; Black Lives Matter protesters openly condemned by the local sheriff; NAACP officials refused entry to the County Office Building by the White county executive and the teenaged son of a White school board member posting video of himself with a scoped rifle threatening to shoot Black residents “for sport.”

As a first step toward remedying these frightening injustices, Black Wicomico voters are asking a federal judge to invalidate the County’s discriminatory election system and order reform. A new system is needed that eliminates the at-large structure and expands Black election opportunities among the seven seats.

Last year, a similar lawsuit in Federalsburg achieved remarkable success after Black voters challenged the all-White municipal government that stayed in place for two centuries even as the community grew to half Black. Through court-ordered reforms, Federalsburg voters made history last September by electing two Black women as the first-ever Black officials in their town’s 200-year existence. What’s more, the Federalsburg plaintiffs went on to secure unprecedented restorative measures – including an official written apology for past racism – as part of their lawsuit’s settlement.

While the Federalsburg and Wicomico activists follow in the footsteps of the bold Eastern Shore voting rights crusaders who came before them, they are also charting a path of their own, highlighting and seizing opportunities for an overdue racial reckoning. Perhaps this can, at long last, bring the reconciliation needed to vanquish the racial injustices of our past.

The post Racial reckoning comes to Maryland’s Eastern Shore appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers.