By Reginald Williams

Special to the AFRO

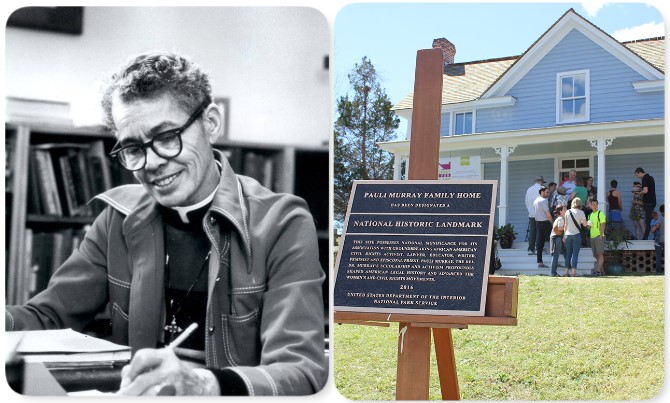

On Sept. 7, the Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice opened to the public in Durham, North Carolina’s West End. The center has been under renovation for some time, according to local news reports. Billed as “A Celebration of Homecoming,” the event drew diverse visitors, all looking to honor and remember the civil rights leader’s work.

“It has been a decade-long journey,” said Angela Thorpe Mason, the center’s executive director, to The Living Church, a religious publication. “The house was slated for demolition in the early 2000s, and was in extremely bad shape. A group of local advocates rallied to save it. The Pauli Murray Center was established in 2012, but the rehabilitation wasn’t complete until this April.

Anna Pauline “Pauli” Murray was a pioneer and a person of many firsts. Born in 1910, the trailblazing civil rights attorney, a 1944 graduate of Howard University Law School, was the only woman in her law class, where she ranked first. She was also the first African American to earn a Doctor of Jurisprudential Science from Yale Law School in 1965.

Murray was also a changemaker in the religious realm. The Episcopal Church at the Washington National Cathedral ordained Murray into the priesthood on January 8, 1977. The Episcopal Diocese of North Carolina specifies that she was “the first Black person perceived as a woman ordained.” Murray is noted as an Episcopal saint.

Her activism was bold.

Four years before Irene Morgan refused to unseat herself in 1944 while riding on a segregated bus in Virginia, and 11 years before a 15-year-old Claudette Colvin set the stage for Rosa Parks’ civil disobedience by refusing to move from her seat on a Montgomery, Ala. bus— “Pauli,” as she preferred to be called, was arrested for disorderly conduct.

The year was 1940 when Murray, while traveling from New York to North Carolina, refused to move from the designated White-only section. Law officials arrested her for violating Virginia’s state segregation laws.

The mission of the Pauli Murray Center is to continue addressing the injustices and inequalities for all people that Murray fought for. Their vision is “To realize a world in which wholeness is a human right for all and not the privilege of a few.”

The preservation of the center, which is the activist’s childhood home, is “supported in part by an African American Civil Rights Grant from the Historic Preservation Fund administered by the National Park Service (NPS), Department of the Interior.” The NPS designated Murray’s home as a National Historic Landmark in 2016.

Born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1910, Murray was said to be ahead of her time.

“She championed the cause of human rights through her work as an author, educator, lawyer, feminist, poet and priest,” states information released by the Pauli Murray Center.

Murray’s work with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Philip Randolph was rooted in her discontentment with inequalities related to Black women and their lack of decision-making power when in grassroot struggles of Black people. Murray is credited with partnering with Bayard Rustin and James Farmer to establish CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) while attending law school. She also co-founded the organization, NOW (National Origination of Women), fighting for the presence of Black women.

“Her legal work laid the foundation for major civil rights advances. Her 1950 book, “States’ Laws on Race and Color,” was hailed by Thurgood Marshall as the “bible” of the civil rights movement,” says Carl Kenney, assistant professor at the Hussman School of Journalism and Media at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “Her legal arguments, particularly on the unconstitutionality of segregation, were influential in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision that ended legal racial segregation in U.S. schools.”

According to information available at the Pauli Murray Center, the ardent activist “fought to lift up women in the civil rights movement, and women of color in the women’s rights movement. She believed that leaving anyone behind on the road to full equality would neglect a part of herself.”

A few years after being appointed by Eleanor Roosevelt to serve as the President’s Commission on the Status of Women, Murray wrote “Jane Crow and the Law: Sex Discrimination and Title VII,” an article that exposed the gender discriminatory practices and laws that outright oppressed women. The impact of that article inspired Atty. Ruth Bader Ginsberg to include Murray’s name on the brief cover written for Reed v. Reed 404 US 71. The 1971 landmark Supreme Court case struck down laws that discriminated against women by using the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, which says no state can deny equal protection of the laws to anyone within its jurisdiction.

“Murray was a key figure in the second wave of feminism…advocating for gender equality and helping to shape the feminist movement’s focus on equal rights and dismantling systemic sexism,” says Kenney.

During an era when the use of nonbinary, non-gender pronouns was non-existent, Murray pushed the boundaries of gender and sexual identity. At 18, Murray shortened Pauline to Paulie to embrace a more androgynous identity. Many published reports maintain that Murray believed she was born a man in a woman’s body.

Rosalind Rosenberg, author of “Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray,” notes that Murray identified “as a female who believed she was a male, before the term transgender existed.

Kenney, a passionate promoter of women’s rights and the LBGTQ movement, says Murray was private about more sensitive topics. Still, many today recognize Renee Barlow as a long-time romantic partner of Murray.

“Although she never publicly acknowledged her sexual orientation, in private writings, Murray expressed feeling like a man trapped in a woman’s body, making her an early figure in the conversation around gender identity,” says Kenney.

She died on July 1, 1985, at the age of 74.

Murray’s impact can still be felt in Durham, where she was raised by her aunt Pauline Fitzgerald Dame, after her parent’s death. The Durham Public School Board of Education recently voted unanimously to name their newest elementary school, Murray-Massenburg Elementary School, after Murray and Betty Doretha Massenburg, the first Black women principal in Durham.

Today, five Murray murals exist throughout Bull City: 1101 West Chapel Hill Street, 2520 Vesson Avenue, 313 Foster Street, 117 S. Buchanan Boulevard, and 2009 Chapel Hill Road, keeping the activist’s memory alive.

The Pauli Murray Center is just one more jewel added to the area, in honor of Murray’s work. According to information released by the center, Murray’s childhood home “was built by her grandparents in 1898 at 906 Carroll Street in Durham, North Carolina.” Today and every day moving forward, the center will keep the name of Pauli Murray alive “by connecting history to contemporary human rights issues” and encouraging people “of all ages to stand up for peace, equity and justice.”

The post Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice opens to public after years of renovation appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers.