By Mylika Scatliffe,

AFRO Women’s Health Writer

September is National Sickle Cell Awareness Month. Sickle cell disease (SCD) is the most common inherited blood disorder in the United States, and it affects approximately 100,000 Americans– mainly African Americans.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “the disease occurs among one out of every 500 Black or African-American births and among about one out of every 36,000 Hispanic-American births.”

“It is most common among people whose ancestors come from Sub-Saharan Africa; the Western Hemisphere (South America, the Caribbean, and Central America); Saudi Arabia; India; and Mediterranean countries such as Turkey, Greece and Italy,” reports the CDC.

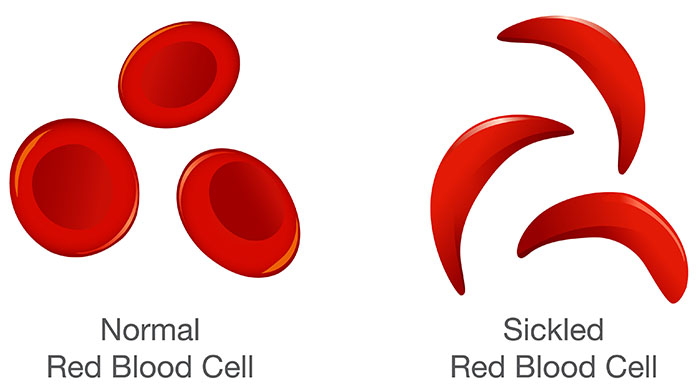

Those with SCD have red blood cells that are crescent shaped rather than round and pliable like normal red blood cells. The “sickle” shape of the cells causes them to die early, causing a chronic shortage of red blood cells. Sickle shaped cells cannot easily pass through blood vessels, so they get stuck and clog the flow of blood. This causes severe pain and other complications in sickle cell patients.

SCD is one of the vast number of health disparities endured by Black people in the United States and globally. This is one of the chief reasons Dr. Emily Rao, a pediatric hematologist-oncologist at Johns Hopkins Children’s Center in Baltimore, specializes in the treatment of children with SCD.

“This might be the best time in history to be born with sickle cell disease with the advances in medications and curative therapies. Fifty years ago, we had to wait for a patient to experience complications before treating them, and the manifestations of sickle cell crises are broad,” said Rao. “One patient may experience severe pain, another may have a stroke. Today with all the treatment advances we can be proactive to try and prevent or reduce the severity of crises and complications.”

“Even so, there is still a lack of education among many doctors and other providers about sickle disease and how it affects those who suffer from it, and we are working constantly to combat the effects of the disease and to make sure the public and providers are well informed,” Rao continued.

Raising awareness decreases the lack of education, combined with other barriers for obtaining care such as healthcare access, health insurance or transportation to specialized sickle cell treatment for sickle cell patients. Sickle cell patients are at significantly increased risk for serious and deadly complications including stroke, acute chest syndrome and bacterial infections.

Dr. Jennie Law, a hematologist-oncologist at the University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore, echoes these concerns. Baltimore city is well positioned when it comes to specialists providing care for sickle cell patients. Clinics can be found at the University of Maryland Hospital, Johns Hopkins, and Sinai Hospital, but the situation is starkly different in Maryland’s rural areas and the country where patients don’t have hematologists who specialize in sickle cell treatment.

“There is a misconception among a lot of doctors that sickle cell patients are always in pain or seeking pain medication. That’s made some adult providers less willing to engage with that patient population,” said Law.

Sickle cell disease is a genetic condition present at birth, inherited when a child receives two sickle cell genes from each parent. Sickle cell trait (SCT) is not the same as having sickle cell disease, but having the trait means a person has inherited one normal gene and one sickle cell gene from each parent. Someone with the sickle cell trait won’t have the disease and likely won’t have symptoms. But they will be a trait carrier and can pass it on to his or her children, so knowing one’s sickle cell status is paramount. In America, blood screenings are performed on every newborn to check for sickle cell disease or the trait, and parents of children who carry the trait or disease are notified within four weeks or so after birth.

Nancy Adams, 37, of Owings Mills, Md., found out she possessed the sickle cell trait once her newborn daughter, Mariah Lightner revealed sickle cell disease.

Now 18-years-old, Lightner has endured many pain crises over her short life as the hallmark of SCD is acute and chronic pain. Babies with SCD usually begin to experience symptoms until they are around one-year-old.

“When babies are born they still have some of the fetal hemoglobin that was produced while they were in the womb, so they usually don’t have symptoms right away,” said Adams. “Even as a baby, Mariah was having pain in various places – sometimes her legs, sometimes her stomach and she would get a lot of fevers. It was challenging because babies can’t talk and articulate what they are feeling. I’d have to take her to the emergency room or the sickle cell clinic at Sinai.”

Rao described that “the pain from sickle cell can be anywhere from head to toe, but blood often gets clogged up in large muscles like the thighs, back, butt or arms.”

Because SCD is a blood disorder, patients are more susceptible to infections. They frequently have blood drawn to be proactive in managing infections. Even with typical childhood infections, children with sickle cell will get sicker than others and often endure frequent hospitalizations.

“My daughter had a lot of absences in elementary school because of hospitalizations from pain crises. Fortunately, there was a program at the time where someone would come to our house with her schoolwork and go over it with her to make sure she didn’t fall behind,” Adams recalled.

What does awareness look like?

Adult sickle cell patients, particularly those in an area of the country with low Black populations, may encounter bias when seeking care. Providers who are not educated about or exposed to sickle cell may not understand the severity of a patient’s pain or may even suspect they are drug seeking.

“Someone in the midst of a sickle cell crisis may look good and have normal vital signs. Sickle cell disease is lifelong, which means patients have adapted to pain,” said Rao. “A patient can do everything we tell them, do everything right and still have a crisis. That’s the nature of the disease. It’s important to be followed by and keep regular appointments with a hematologist.”

“If one of my patients is having a crisis and needs to go to the emergency room, I will call ahead and advocate for them,” Rao continued. “I’ll let the staff know a sickle patient is on the way and their medications and normal treatment protocol.”

This type of advocacy is crucial when encountering medical staff who have acute knowledge and experience with sickle cell patients. “It’s best for SCD patients to be proactive in preventing complications and followed by a hematologist,” stated Rao.

“There’s been advances in the management of sickle cell disease as well as movement toward curative therapies. In 2023 there is a cure for sickle cell – a bone marrow transplant, which was pioneered by the National Institutes for Health about 15 years ago,” said Law.

Law encourages Black people to get on national donation registry programs. “Minorities are very underrepresented in the marrow donor registry program,” Law said.

Besides knowing about the symptoms and treatments for SCD, Lightner thinks it’s important to know what it’s like to love someone living with sickle cell. “It’s important to acknowledge small things and be mindful. Small things like the temperature of the air conditioning and the physical activities you plan can trigger a pain crisis,” said Lightner as her mother concurred.

“Sickle cell is a disease that causes pain which means people that have it have been dealing with it their entire lives. They’ve learned to live with and won’t always look really bad, but you should know and expect that there will be times they are in pain,” said Adams.

“First, you should make sure to know your sickle cell status. Next, paying attention to how your loved one looks and feels when you do things together and making sure they are not overworked with strenuous activities is really important,” said Lightner. “We might feel left out because we’re not able to do a lot of the things other people can. Making sure your loved one feels included and appreciated is really important.”

The post National Sickle Cell Awareness Month- do you know your status? appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers .