By Amber D. Dodd

Special to the AFRO

adodd@afro.com

To celebrate Black History Month, The National Links Trust (NLT), a non-profit organization created to protect and promote municipal golf courses, showed the documentary “Uneven Fairways” on Feb. 20. The screening took place at the Rayburn House Office Building on Capitol Hill.

“The legends of Black golf have forged for inclusion at the highest levels of golf competition for all people,” said Damian Cosby, executive director of NLT.

Released in 2009, Uneven Fairways is narrated by actor Samuel L. Jackson, an avid golfer whose activism and work in Black communities stretches back to being a student at Morehouse College in the 1960s.

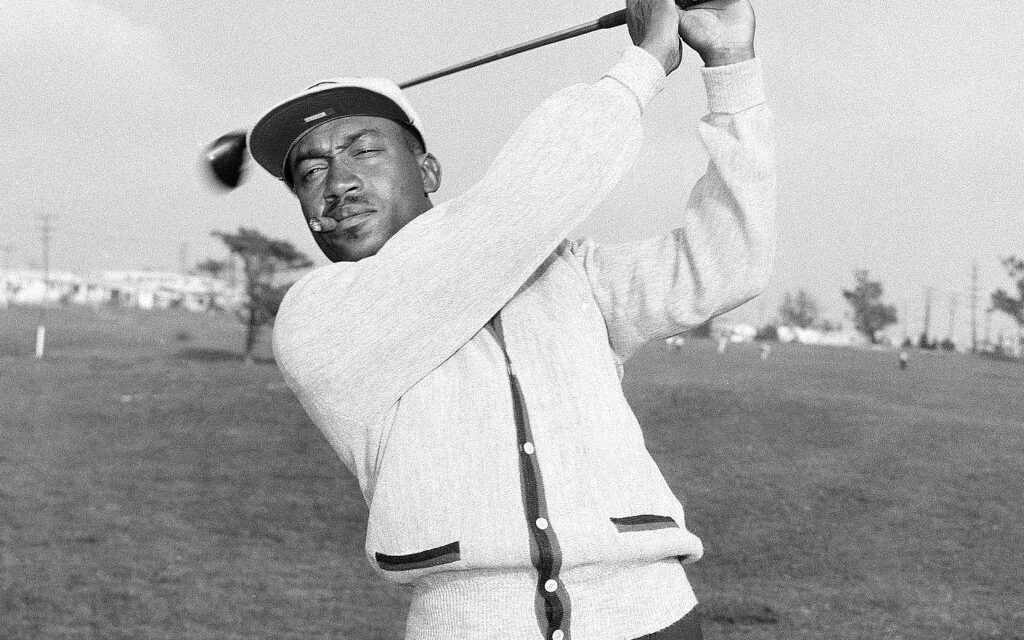

The film highlights the pantheon of Blacks–from Pete Brown, the first Black golfer to win a PGA Tour event at the 1965 Waco Open, to Jim Thorpe, a 75-year-old golfer and Morgan State University graduate with 21 professional wins–who reflect the vanguard of Black golfers who were barred from the professional ranks but persisted in the sport until the PGA’s racial barriers ceased in 1961.

Peggy White, the daughter of Ted Rhodes appeared in the documentary, too; Rhodes was widely considered to be the greatest Black golf player before Tiger Woods’ emergence.

Rhodes did not get a chance to compete on the PGA Tour.

“I don’t think my father was aware of the trailblazer he was,” White said. “He had a dream that he would be the finest golfer in the world, but I don’t think he realized he accomplished that goal.”

Throughout the film, golfers detail how the PGA’s color barrier was upheld by a longstanding clause in the PGA. From 1929 to 1961, Article III Section I of the PGA’s handbook stated that

“Male professional golfers of the Caucasian race, over the age of eighteen (18) years, residing in North or South America, who can qualify under the terms and condition hereinafter specified, shall be eligible for membership.”

While the documentary tells the story of the individual experience of being Black in golf, Uneven Fairways also highlights the founding of the United Golf Association, commonly known as the Chitlin Circuit, which provided Black golfers opportunities to compete.

“Black people, being very resourceful, wanted to play and so in 1925, a group of Black businessman met in a YMCA in Washington D.C. and basically said ‘Well, PGA won’t let us play on their tour, so we’ll start our own tour,’” said Pete McDaniel, author of Uneven Lines: The Heroic Story of African-Americans in Golf.

Later that year, the first National Negro Open was contested.

The Chitlin Circuit served as an incubator for many of golf’s first popular Black players and served as fertile ground for future golf giants.

Speaking to the documentary’s name, golfers talked about the conditions of golf courses that UGA players conducted golf tournaments on, citing shoddy landscapes and uneven grounds, usually played on municipal golf courses.

“One of the reasons why I love municipal golf is that it brings people together,” Cosby said. “It’s the easy way to get a young Black kid who’s probably never seen as much green grass on a golf course to keep them out there. That’s what I love about , it connects people to the game and brings people to the game.”

Inclusivity was no question for the UGA. Black women were automatically members of the association. Renee Powell, the second Black woman to participate in the LPGA tour, who spoke about her admission into UGA as a teenager golfer was mentioned in the documentary.

“All the young Black golfers, that’s where they played,” Albert Green, a UGA/PGA player explained. “Lee Alder, Charlie Sifford, Calvin Peete, Teddy Rhodes, that’s where those guys got their start.”

Ron Terry called the Chitlin Circuit a family-affair, “It was a tour where you got to know everybody,” he said. “It was more like a fraternity than anything.”

Many mentioned how players supported one another on efforts on and off the course.

“We all traveled together anyway, so we helped each other…if you were hungry, we’re going to feed you, we weren’t going to let go around hungry,” Leonard James explained.

Members often paid for and provided their own resources which they were happy to share with others.

“They were going to eat because I always carried electric pots with me, and a frying pan,” James Black joked back.

Although an alternative league was created, it was still very clear that the color line imposed barriers that didn’t impact White athletes.

“It was a joy to be around but it was separate, totally separate and not equal,” said John Merchant, a former USGA executive committee member.

Though golfers made their own efforts to break the color barrier of the golf world, the documentary shed light on how Joe Louis, the former heavyweight champion broke the color barrier in the PGA-sanctioned tournament in 1952 San Diego Open. Louis spoke against the PGA as they would become the final major American sports corporation to integrate Black athletes.

Louis’ son, Joe Louis Barrow Jr., spoke on behalf of his father’s racial contributions in both boxing and golf. “If you ask any of those older golfers, the reasons they’re playing golf today, or throughout their career is because of Joe Louis,” Barrow said.

Along with streaming Uneven Fairways, NLT specializes in restoration of municipal golf courses, including the Langston Golf Course in Northeast D.C. which highlights their mission of exposing more youth of color to the game of golf via public golf courses.

“For us at NLT, we personally have a special connection to this story, Langston was built for Black players in the age of segregation,” Cosby explained. “It opened in 1939 and is one of the oldest Black golf clubs in the country.”

In light of Black female golfers, members of the Wake-Robin Golf Club were in attendance. Founded in 1937 in Lanham, Md., it is America’s oldest African American women’s golf club. Debbie Tyner, president of the Wake-Robin Golf Club, said the legacy of Powell and those alike set examples of newer generations of Black female golfers.

“This club is 87 years old this coming year and we continue this work by bringing on members and amateurs,” Tyner said. “They pass on the legacy of Black women in golf…and I want to see the club change with the times. We’re partnering with Howard University who have a very strong women’s golf team, and we work with them to provide them with scholarship and mentorship, so in turn, it becomes an intergenerational thing.”

The post National Links Trust celebrates Black golfers with ‘Uneven Fairways’ documentary screening appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers.