By John Harris

He was born when slavery was still a fixture in American society and played shortly thereafter

The legacy of Moses “Fleet” Fleetwood Walker as the first African-American to play professional baseball is changing the narrative of sports history.

Born in Mount Pleasant, Ohio, and raised in Steubenville near the Ohio-West Virginia border, Walker played catcher during the 1884 season for the Toledo Blue Stockings of the American Association, which competed with the National League. Although Jackie Robinson is widely recognized as the first African-American to play in the Major Leagues, Walker is acknowledged by historians at the National Baseball Hall of Fame to actually be the first, six decades before Robinson suited up for the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947.

Robinson’s story of enduring racism and overcoming prejudice to become one of baseball’s all-time greats was accomplished amid great personal sacrifice during a period of upheaval in the United States when African-Americans were seeking equality with whites in education, housing, voting, and basic human rights. He was voted to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962 and died 10 years later at age 53.

Walker, who was 67 when he died in 1924, was born during a turbulent time when slavery was still a fixture in American society. Growing up as a free man, he overcame insurmountable odds and broke into professional baseball 19 years after the end of the Civil War. He played in the minor leagues until 1889, when baseball enforced a color barrier that remained in place until Robinson’s arrival.

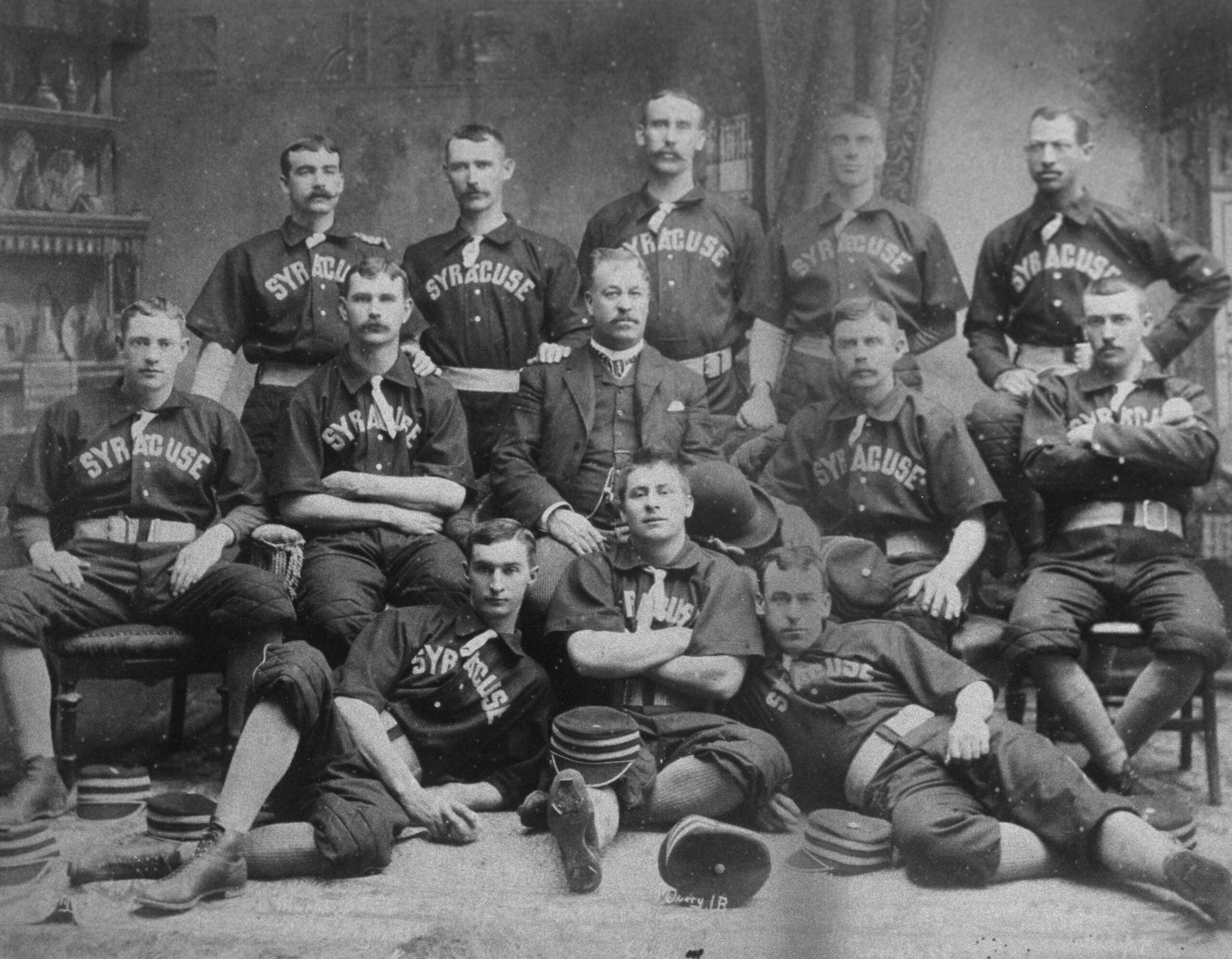

The son of a black father and a white mother, Walker was also the first African-American to play baseball at Oberlin College and the University of Michigan. He was acquitted on a second-degree murder charge in Syracuse, New York, when an all-white jury ruled that he stabbed a white man in self-defense. A 2015 play titled The Trial of Moses Fleetwood Walker depicted the 1891 racially-charged courtroom drama. Walker was later sentenced to one year for mail fraud.

Following a distinguished baseball career that once earned him the princely sum of $2,000 for six months of work, Walker purchased a hotel and a movie theater, and he also published a weekly newspaper.

“The Moses Fleetwood Walker story is an American story about a constant need to fight for justice, equality and freedom,” said state Rep. David Leland of Columbus, Ohio, who reintroduced legislation Feb. 13 with fellow state Rep. Thomas West of Canton to designate Oct. 7 (Walker’s birthday) as Moses Fleetwood Walker Day in Ohio. “Hopefully, my colleagues in the Senate and House will agree with me that this is an important part of American history that we need to remember.”

Walker debuted in the Major League on May 1, 1884. Often catching barehanded and playing without a chest protector, he hit an impressive .263 in 42 games, surpassing the league batting average by 23 points. The Toledo Blade wrote: “Walker has played more games and has been of greater value behind the bat than any catcher in the league.” When younger brother Weldy (Wilberforce Walker) joined the team and played in six games, the Walkers gained the distinction of being the first two African-Americans to play in the Major Leagues.

Moses Fleetwood encountered few friendly faces among opponents, fans, or even his teammates. He was derided by spectators angered by his presence on the field with white players. An inviting target for opposing pitchers, he was plunked by pitches six times in 152 at-bats. His own pitcher, Tony Mullane, admitted years later that he ignored signals relayed by his African-American catcher and threw whatever he wanted. As a result of not knowing what to expect, Walker suffered numerous injuries, including a broken rib.

“When he played, there were Jim Crow laws. They spiked him. They spit on him. They did everything they could. There was open discrimination, and he still played,” said state Rep. Michael Ashford of Toledo, the minority whip of the Ohio House of Representatives.

In April 2002 as a member of the Toledo City Council, Ashford was part of a local contingent honoring Walker when the Triple-A Mud Hens opened at Fifth Third Field. Today, fans enter Fifth Third Field through the Moses Fleetwood Walker Plaza in front of the main gate.

“I spent money on Moses Fleetwood Walker T-shirts to send 100 kids to the very first game in the new stadium when the city of Toledo recognized him,” said Ashford.

An unofficial ban fueled by a rival player, Cap Anson, who was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1939, kept African-Americans out of the Major Leagues for the next six decades. When Anson refused to take the field against the Walker brothers, other white players followed suit. By the early 1890s, no African-Americans were playing professional baseball.

“When Moses Fleetwood Walker played, there were people in those crowds that owned slaves at one time. There were people in those crowds that were slaves at one time. If you think race relations are rough now, think of what they were like in 1884,” said Craig Brown, adjunct instructor at Kent State and Stark State College and a Society of Baseball Research (SABR) member who led fundraising efforts to purchase a headstone for Weldy Walker’s gravesite (next to his brother Moses’ gravesite). “In the culture of that time, people weren’t sure how biracial society would survive. The idea of social Darwinism was very evident.”

Brown continued: “When Moses Fleetwood Walker played, people had never seen African-Americans of his caliber before. You’re talking about an African-American baseball player who was at the top of his game, and intellectually sharp as a tack. In these trying times, with so much division right now, so much violence and so much misunderstanding between groups of people, we need this story. It’s a sad story, but so inspirational.”