By Rebecca Griesbach

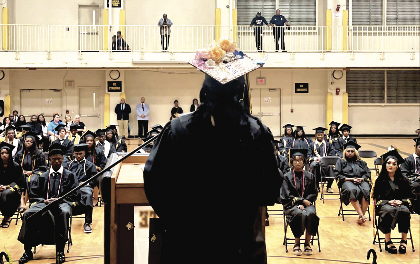

Keziyah Morgan didn’t mince words when she took the stage Tuesday evening.

In her salutatory address, the LaFayette High School senior reminisced over the joyous, comedic and sometimes difficult moments she shared with the small class of 45 students – including learning this year that the school may be closing.

“But thankfully, we’re still here graduating with our LaFayette High classmates,” she said. The gym, packed from top to bottom with families and community members, shook with applause.

Morgan’s tight-knit senior class could be the last to graduate from LaFayette High, a small, rural high school in Chambers County, pending a decision from a federal judge.

The school district is one of dozens in Alabama that are still bound by decades-old court orders, originally issued after Brown vs. Board of Education in an effort to desegregate local school systems. To this day, officials say majority-Black Lafayette High and majority-white Valley High, the district’s two high schools, lack the same opportunities.

In an effort to cut costs and relinquish court oversight, system leaders are pushing to merge the two schools as early as next fall – a move that has left many LaFayette residents concerned.

Across Alabama, several small, rural majority Black schools shut their doors in the past decade – usually due to enrollment declines or financial issues – though it’s rare for a court to intervene in those decisions. But in 2021, a federal judge ordered R.A. Hubbard High, the only majority-Black school in Lawrence County, to close in a similar court case. And last year, a judge permitted Chambers County to close three middle and elementary schools, as part of the beginning stages of its desegregation plan.

Many now worry what a closure would mean for the town’s economic well-being, and are growing more and more concerned about the burden it would place on Black students and families.

“I believe that the community, the students, even myself – there’s this overarching belief that LaFayette isn’t getting a fair shake in this consolidation,” Kelsey Barnes, a local pastor, told AL.com this winter.

A ‘tug of war’

Court proceedings began last summer and continued through the fall, as district leaders deliberated over a site for the new consolidated school in Chambers County, a farming region north of Auburn that has been losing population for decades.

Despite earlier agreements to build the high school in a neutral location, the Chambers County school board announced this year that it planned to accept an offer for land in Valley, a majority-white but diversifying city on the eastern edge of the county.

In January, a weeklong federal trial drew protests and a packed crowd of Chambers County parents, students and community leaders to the state capitol.

“Equity over equality! Displacement is racism!!” a group of LaFayette teachers chanted down Church Street that week, across from a courthouse named for Frank M. Johnson, the judge who first ordered Alabama schools to desegregate in 1963.

“The new school should not put those communities at more of a burden,” a LaFayette tenth-grader said at another protest, noting that moving to a new school would be more “distracting” than productive.

Barnes, the pastor, often works with students at LaFayette. He said the developments have taken a toll on local families.

“Kids are really being traumatized by this announcement, and they really got to a point that they gave up hope,” he said. “Prom Queen, Prom King, Mr. and Miss LHS, these things have mattered for generations at the city of LaFayette and LaFayette High, and now it seems to be all for nothing.”

In court this winter, Superintendent Casey Chambley called the decision to merge a “numbers game” that, he felt, was unavoidable.

LaFayette High has 19 teachers, compared to 47 at Valley, according to state data, and not all are funded with state money. Chambley said that means there is little room to provide extracurriculars at LaFayette, as well as other academic and athletic opportunities.

Due in part to the small size, the district, which has one of the lowest property tax bases in the state, is also paying about 50% more per pupil at LaFayette than Valley, he said.

“Any time you close a community school, it’s tough on the community,” Chambley said on the stand, adding a moment later: “However, we can’t let things stay how they are.”

The NAACP, on the other hand, argued that the district had failed to keep its word that it would build a school in a neutral location.

A GIS expert, Matthew Cropper, said the site selection process was “incomplete and not comprehensive and inequitable,” and that analysts did not use accurate measures when determining travel times between potential sites. After the trial, Travis Smith, a consultant who was tapped to help the district with its desegregation efforts, publicly criticized the board’s analysis.

“How do you sleep at night knowing you made a decision based on incorrect and inaccurate data?” he asked them at a school board meeting.

District leaders acknowledged that the plan was imperfect and that, in a rush to get construction underway, they did not fully investigate all possible options.

In a brief filed last month, school board attorney Robert Meadows stressed the difficulty of balancing financial challenges with the ongoing litigation.

“[The district] is faced with complying with Court Orders and with being able to finance and pay for the new school while sustaining the Board’s financing for operations,” he wrote. “It is in a ‘tug of war’ with two different communities, and it must endeavor to provide their students with everything that they need as best they can.”

‘Impatiently’ waiting

In many ways, the district has already started planning for changes next year. It polled parents this month on potential names for the new, merged school. Leaders hope to be able to temporarily move all high schoolers to Valley High School in the fall.

“We are still waiting on a ruling,” Superintendent Chambley said in a board meeting last week. “We wait patiently, or rather impatiently, on that. And we hope any day now we will have a decision, so that we can move forward in our district.”

Chambley and other board members filed into a row of chairs next to the stage Tuesday evening as the district celebrated its second of the two high school graduations.

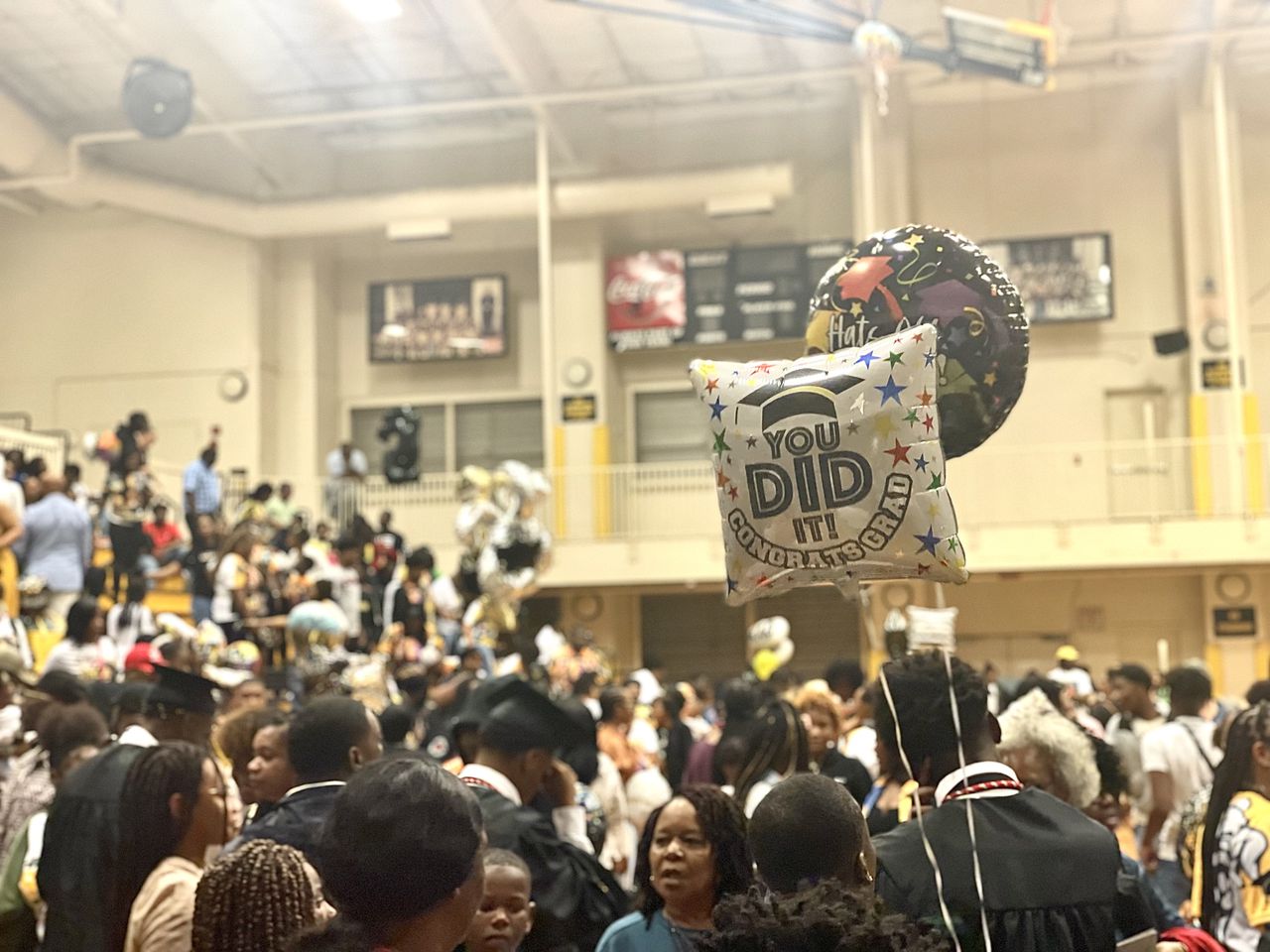

The LaFayette High School gym was so packed that some guests overflowed into the second-floor rafters. Hundreds of family and community members, many sporting black and gold and Class of 2023 T-shirts, had come out to celebrate the graduates.

After Morgan’s speech, valedictorian Emrald Wilkins took time to honor each of her 44 classmates.

She knew what their aspirations were, where they were going to college, and what she imagined they’d be doing years from now.

“I can see Kayla Calloway now, being such an amazing psychologist,” she said, before joking with one of the boys. “I can see DeMarrion now… giving us discounts on our car parts.”

One by one, each received their diploma.

Christy Brock-Johnson, hired this year to be the school’s principal, beamed at the graduates. The class had a 100% graduation rate, she said, and several had racked up hundreds of thousands of dollars in college scholarships.

Before moving their tassels, Morgan, Wilkins and another student led the seniors in song. Speakers blared Nicki Minaj as the group of girls swayed together, laughing and belting into the microphone.