By Barnett Wright | The Birmingham Times

This story is republished with permission from The Birmingham Times

The Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing was not the only tragedy in Birmingham on Sept. 15, 1963. Four girls — Cynthia Wesley, 14, Denise McNair, 11; Carole Robertson, 14; and Addie Mae Collins, 14 – were killed in the blast.

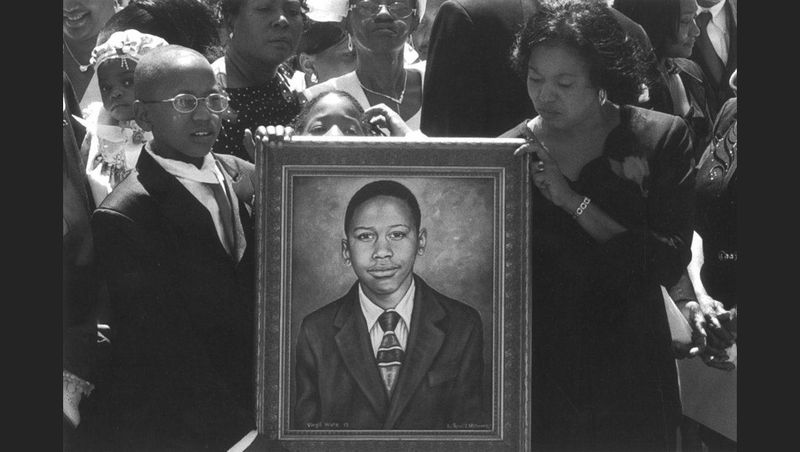

Many members of the Black community were further shaken when they heard that 14-year-old Virgil Ware had died that same day at the hands of two young white men, Michael Lee Farley and Larry Joe Sims.

Ware was killed on his way back from Docena, a community just outside Birmingham, where he and his brother James had gone to buy a bicycle for Virgil’s paper route. They didn’t find the bike at their uncle’s scrap yard, so they rode back toward their home along Docena-Sandusky Road. That’s when they encountered Farley and Sims.

Ware’s brothers, James and Melvin, recalled the events of that day, according to a book, “Foot Soldiers for Democracy: The Men, Women and Children of The Birmingham Civil Rights Movement” by Horace Huntley and John W. Kerley.

James: “When Virgil got shot, I really didn’t know that [Sixteenth Street Baptist Church] had been bombed. I don’t guess I knew anything until the next day. We left early that morning and went to (our) church, and I don’t think we told anybody we were going to pick up the bike. We left early, and we stayed out there all day riding around. It was something like a junkyard more or less, just riding around on a bike. I didn’t know anything about the church until the next day.

“That particular Sunday, we were on our way back. Virgil was on the handlebars, riding along. I was pulling him. I was bigger than all the rest of my siblings. They were little com pared to me. I looked like my daddy. We saw a bike coming from the other direction [with two white boys on it]. We just kept pedaling. They got so close that they just overcame us.

“When Virgil got shot, he said. ‘Wow, I’m shot.’ He just fell off the handles and fell to the ground. I stood over him, and I guess five or six minutes later a car came by, and I told them what happened, and I told them where we stayed …. They turned around and brought my mom and dad and people down there. He was dead by that time. He didn’t say anything after that, after he said, ‘I’m shot.’ He was 14, and I was 16.”

Melvin: “That day I was watching a football game. James and Virgil had gone to Docena to purchase a bicycle from my uncle. They flashed on the news about the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. I just shook.

“I was just about 12, and my mind dawned on my brothers. I thought about their safety during that time. When they weren’t back after about two p.m., I just walked and was tossing and turning. My mother had gone to the usher board, and when she had gotten back, a lady asked her if all of her children were home. She said, ‘No, two of them are not at home.’ The woman said, ‘You better come with me.’

“That’s when she went and found my two brothers. Virgil had been killed, and James was out there. The whole experience affected me deeply because it was like a piece of pie. You bake a pie, and then you take the pie out, you have a piece missing. That’s really how it affected me. I thought about what Virgil would be doing now if he were still living. I would’ve liked to see him grown like us and have a family.

“It was real sad when I had to go back to school. My teachers and classmates had taken up some money to buy flowers at the funeral, and everybody gave their condolences and told you how sorry they were. It was sad … I lost my brother over nothing.

“At the time, I thought it was all for nothing. But as time goes by, I believe it was for a reason. I believe there’s a reason for everything. No question about it: that day launched the Civil Rights Movement with the bombing of the four girls and Virgil’s death.”

James: “I remember the day my brother was shot ‘cause I stayed there with Virgil so much. I don’t even remember who stopped and went and got my mama and daddy. I believe those people were white. Anyway, they went and got my parents. When I went home, I didn’t come out the house no more. I told the police what happened. That’s all I did. I told them it was two guys (on a bike). The one on the back did the shooting. I had to testify at the trial.

“The first time I had seen [Farley and Sims] was at the trial. They had said at the time that they thought we had rocks. We didn’t have anything. Virgil had both his hands on the handlebars, and it took all I had to pedal, so we didn’t have anything. At the trial, that was never brought up. If it was, I don’t remember. They asked me to point him out, and I pointed to the two guys. I never knew how the police found them that quick, I tell you the truth. When they came to my house, I remember [a detective] saying, ‘I think we got a lead on who they were.’ Next thing I know, we were at the grand jury, and they went on with the trial.”

Farley and Sims were convicted of second degree manslaughter and sentenced to seven months in jail, but a judge later reduced the sentence to probation because, in his words, “They came from good families;’ according to a report in the Chicago Daily Defender.

“The verdict wasn’t right. I figured they would have gotten more than what they did for what they did. To tell you the truth, I didn’t expect them to catch them. Thank God that they did. I never thought they would. One (Farley) of them did call to apologize. He said, ‘I want to apologize for what happened,’ and he said, ‘I know how it feels, I lost a nine-year-old son.’ We didn’t go into any details about it, though. I went on and accepted the apology because you can’t go around hating the world. Let the Lord take care of that,” James said.