Some loners learn just as easily as more sociable creatures, according to the findings of a new study on related species of birds.

An international team of researchers has found that California scrub-jays, which live in mated pairs, learn just as well as Mexican jay birds, which are social and flock when feeding. The discovery, published in the journal Scientific Reports, means that animal behaviorists may have to rethink the accepted theory that animals living in groups tend to be smarter than their mated peers.

“Further studies with wild animals are clearly necessary to develop a better understanding of when, where and why intelligence evolved,” said researcher and study co-author Jonathon Valente of Oregon State University.

The authors believe that their discovery underscores the complex link between the evolution of intelligence and social behavior and may have ramifications for understanding human intelligence.

Having devised a novel food puzzle to study animal cognition, the scientists had expected the sociable Mexican jays (Aphelocoma wollberi) to outperform the closely related California jays (Aphelocoma californica).

Both species are opportunistic, generalist foragers that feed on tree nuts such as acorns and prefer dry, open habitats of pine and scrub oak. They also similarly cache food. However, Mexican jays flock in groups of five to 30, while the non-social scrub-jays live with a single mate.

Both species are related to the blue jay, which is well-known in the eastern part of the United States. The three species belong to the Corvidae, or crow, family of birds.

Animal behaviorists sought to discover why some species developed with greater intelligence than others, coming up with the theory that those living in groups were smarter because they would require more complex levels of thinking than species that are not so social.

“The group-oriented animals rely on intelligence to cooperate with and learn from — and also deceive — their group mates,” said lead author Kelsey McCune.

McCune noted that until now, the theory had not been tested on wild animals because of “the difficulty of testing cognition outside the laboratory.”

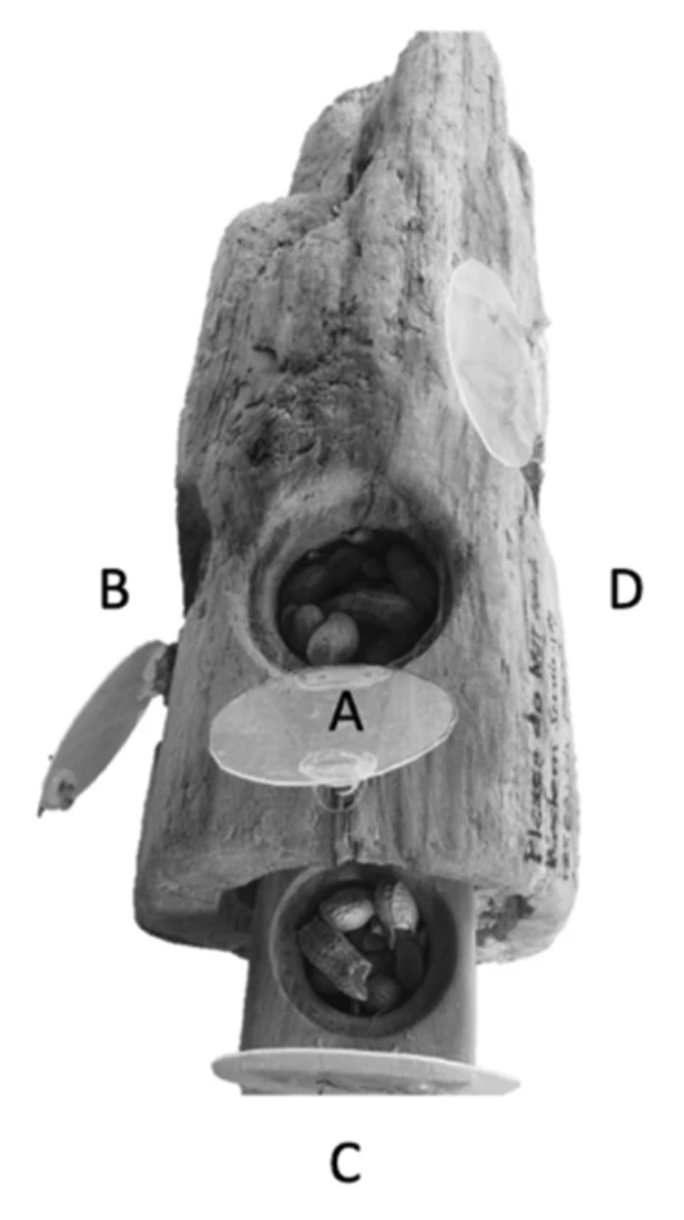

To test the theory, McCune and Valente joined colleagues in South Korea and developed two identical puzzle apparatuses fashioned from logs. Three out of four doors on the log had a simple lock, while another was unlocked and featured a less preferable food: sunflower seeds. The birds showed a stronger preference for the peanuts locked behind doors.

Researchers trained a demonstrator bird from each of the two species to open locked doors before setting them free among wild birds along with the puzzles. They observed some 49 Mexican jays in Arizona and 25 California scrub-jays in Oregon attempting to extract food from the puzzles.

“Having an unlocked door helped prevent ‘naïve’ jays from abandoning the foraging area due to a failure to get food, thus increasing their probability of observing group mates interacting with the puzzle,” Valente said.

“We compared intelligence between these species by testing their abilities to either innovate a solution to the puzzle or to learn to solve the puzzle by observing other birds solving it,” McCune said. “Contrary to what we thought we’d find out, the two species showed similar abilities to learn.”

The researchers found that Mexican jays learn by watching other birds trying to solve the puzzle. But scrub-jays appeared to be more self-reliant when obtaining food.

“Surprisingly, members of both species tended to avoid interacting with parts of the puzzle where they observed other birds obtain food,” said Valente.

He believes this means the birds rely on social learning to avoid competition rather than to learn how to open the puzzle for the food. “Regardless, the findings suggest the relationship between social behavior and the evolution of intelligence is a highly complex one,” he said.

The study concluded that “both species used social information to avoid, rather than copy, [members of the same species]. Our findings demonstrate that while complex social group structures may be unnecessary for the evolution of social learning, it does affect the use of social versus personal information.”

Edited by Siân Speakman and Kristen Butler

Recommended from our partners

The post Loner Jays Learn Just As Well As Social Jays, Scientists Say appeared first on Zenger News.