By Aria Brent,

AFRO Staff Writer

Known for his work as a cardiologist, Dr. Levi Watkins Jr. was much more than the first person to successfully implant an automatic heart defibrillator– he was a pillar of the Johns Hopkins Hospital community. In 1980, he performed the world’s first implantation of an automatic heart defibrillator in a human–introducing a surgical procedure that would save the lives of untold patients experiencing a sudden interruption in the natural rhythm of their heartbeat.

In addition to being a pioneer in the medical field, he was a civil rights activist. An alumni of both Tennessee State University and Vanderbilt University, Watkins was the first student to integrate and graduate from Vanderbilt’s school of medicine.

His trail blazed at Vanderbilt would go on to be one of many. During his tenure at Johns Hopkins Hospital Watkins was the first Black chief resident and later became the first Black full professor.

Having grown up during the civil rights movement, Watkins was extremely passionate about presenting more Black students with the opportunity to further their education and pursue medical careers.

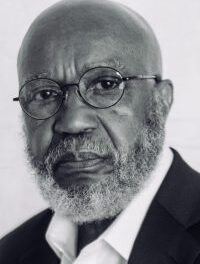

(Photo Courtesy of Vanderbilt University)

“His impact at Johns Hopkins and beyond was significant in the area of civil rights. When he was awarded a residency at Johns Hopkins, he saw the Baltimore area [had] a lot of the same discrimination and discrepancies that he was seeing in Alabama and Tennessee,” said older sister, Annie Marie Garraway. “That motivated him– especially not seeing a lot of [Black] people above the service staff level at the hospital. [It] motivated him to go on a lifelong journey of civil rights– trying to increase the number of African-American medical students admitted to Hopkins. [He wanted] to help them navigate that environment so that they could graduate and go on to be successful.”

Watkins implemented a variety of programs that helped recruit more minority students to Johns Hopkins Hospital and reshape the culture at the institute. The contributions made by the legendary surgeon can still be seen and felt today. Scholarships and programs have been created in honor of Watkins, but Johns Hopkins Hospital is assuring that his legacy is forever recognized by renaming their main outpatient center after him.

“We had some buildings across the university that didn’t have names and what the university has really been wanting to do is rename these key visible areas on each of our campuses. We want to actually add the legacy of those who really were trailblazers for the underrepresented community, so that they are acknowledged and remembered,” stated Dr. Sherita Golden, when asked how the decision to rename the outpatient center after Watkins came about.

Golden is a professor in the School of Medicine at Johns Hopkins Hospital and also serves as vice president and chief diversity officer for Johns Hopkins Medicine. She first met Watkins in 1989, when she applied to Johns Hopkins University for medical school after having graduated from the University of Maryland-College Park.

Noting that Watkins was a humble man, she recalled him talking to her about being kind to everyone at the hospital and the importance of creating personal relationships with them,

“He told me when I was an intern ‘don’t get so high on your horse that you stop speaking to all the people that are really supporting the hospital,’” Golden recalls. “He was friends with the environmental service workers, the patients, the transport staff– everybody! When you were talking to him, you felt like nobody else was around, like you were the only person that was important.”

Fondly remembered by many for how personable he was, Watkins was known not only for his work as a medical professional and activist, but as a mentor as well.

Dr. Damani Piggott is associate vice provost for graduate diversity and partnerships, an associate professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins Hospital and a former mentee of Watkins. Piggott told the AFRO about how much he benefited from the guidance of Watkins.

“I am just one of the very many who benefited from Dr. Watkins tremendous contributions here at JHU,” said Piggott. “I was a beneficiary of all the impactful modalities through which Dr. Watkins created an exceptional community in our space.”

Piggot further described Watkins as “an exceptional physician, outstanding societal leader, and devoted mentor.”

While working as an associate dean and mentor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, he developed the nation’s first postdoctoral association, continued his advocacy for fairness and diversity, and spearheaded a drive to recruit minority applicants.

Although Watkins passed away in April 2015, many of the initiatives created by him are ongoing and his mission of bringing more diversity to Johns Hopkins Hospital is still being fulfilled.

In 1982, he launched the annual Martin Luther King Jr. Commemoration, which is known for bringing renowned speakers and honoring Johns Hopkins employees for their community service.

“I think one of the most impactful things he did was to initiate the MLK commemoration program. We just had the 40th year of it this past year and what he did was bring all those civil rights luminaries to Johns Hopkins, in the flesh to our auditorium. People like Harry Belafonte, Cicely Tyson, Rosa Parks, Coretta Scott King– just all of these inspirational figures. What that did was it allowed those voices from the civil rights movement to be heard at Johns Hopkins,” exclaimed Golden.

The renaming ceremony for the Johns Hopkins main outpatient center will be held on June 8, 2023.

The post Johns Hopkins Hospital to rename outpatient center in honor of first Black chief resident, Dr. Levi Watkins appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers .