When Jerome Featherstone Jr. made his professional mixed martial arts debut against Matt Semelsberger in October 2018, he entered the ring feeling as if he had the strength of two men.

The Frederick, Maryland-based Semelsberger felt the full force of that power as Featherstone scored a third-round knockout in his inaugural berth in Shogun Fights XX at Royal Farms Arena in Baltimore.

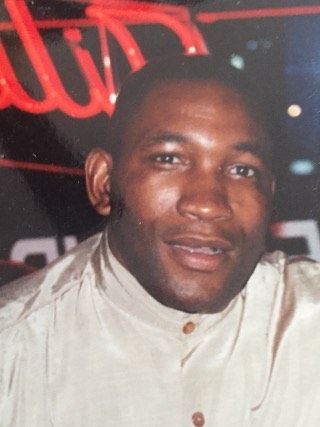

Featherstone’s 170-pound triumph over a fighter whose 3–1 record included three appearances at Shogun and two stoppage victories came 14 years after the death of Jerome Featherstone Sr. in January 2004 at the age of 43.

Slippery conditions caused Featherstone Sr.’s car to crash as he drove up Interstate 95 to his Harford County home from his job as a Homeland Security immigration agent in Arlington, Virginia. Featherstone Sr. died in transit as an ambulance drove him to Fairfax Hospital in Fairfax, Va.

“I’m still hurting over my father’s death. It was during such an important and pivotal time in my life,” said Featherstone Jr., 37, twice an All-Metro First-Team selection by The Baltimore Sun before graduating from Boys Latin High in 2003.

“I was at a crossroads and had multiple paths to choose from. My dad was a great role model to many and he loved his family. It’s my job to honor him and to remain on a path toward greatness.”

Featherstone’s path continues with Saturday’s Shogun Fights XXIV in a 155-pound (super lightweight) bout against Philadelphia’s Steve Moleski at the Maryland Live Casino in Hanover, Maryland, as the Baltimore native ends a 28-month ring absence since a third-round submission loss to Robert Watley in November 2019.

“Since my last fight, I’ve gotten married on July 24, 2020, and we had Jameson Jerome Featherstone on March 17, 2021,” Featherstone said. “I try not to think about my dad when I look at my son. Anytime I do, I begin to cry. I can only imagine the two of them together.”

Featherstone is 2–1 with two knockouts, working and training at Title Boxing in Owings Mills, Maryland, where he is a full-time salesman, teaches group fitness and serves as a personal trainer.

“Stephen Moleski has been in the cage 11 times with a record of 3–8. Most of his fights have gone the distance,” Featherstone said.

“I know he’s a game opponent. I’ll be looking to stop his takedowns. I’d like to beat him up and knock him out in spectacular fashion, like the Semelsberger fight.”

Owned and promoted by John Rallo, Shogun Fights is televised nationwide on a variety of platforms.

“Saturday’s show has been sold out for more than a month,” giving its competitors plenty of exposure, Rallo said.

“Jerome will be using his wrestling to stay on his feet and look for the knockout,” Rallo said. “Steve will try to close the distance and work it to the floor where he can use his Jiu Jitsu skills.”

Featherstone is considering a contract with Wild Bunch Management, which has guided Semelsberger to an overall record of 10–3 with six knockouts and a submission, and 4–1 (2 KOs) in the UFC.

“I just haven’t pulled the trigger on that,” said Featherstone, adding that a solid performance could be lucrative. “With a decisive win in my next fight, the ball is still in my court.”

Featherstone has lived with his wife, Amy, and their 1-year-old son in a three-bedroom home in Westminster, Maryland, since October, and will likely place Jameson in sports at an early age.

“Jameson was holding his head up at three months old, and he took his first steps at eight months. No doubt we’ll see how Jameson takes to wrestling with both his parents being athletes,” Featherstone said.

His wife, Featherstone said, played NCAA Division I lacrosse at James Madison University, leading her team to the Colonial Athletic Conference championship game in 2014, which, they lost in overtime to Towson University.

“So, with Jameson, we know we have some type of athlete on our hand,” Featherstone said.

As for himself, Featherstone had a brief boxing career comprised a pair of four-round decisions in November and December 2015 for a 2–0 record.

“I started boxing because I couldn’t afford my MMA gym dues and I needed boxing in my toolbox. My coaches were Calvin Ford and Kenny Ellis,” Featherstone said. “Calvin trains [three-division boxing champion] Gervonta Davis. I stopped boxing because I didn’t make any money in my first two fights.”

Featherstone followed Semelsberger with a first-round stoppage of Imani Smith in April 2019, a no-contest against Micah Terrill in July 2019 and the loss to Watley.

Overcoming obstacles is nothing new to Featherstone. As a high school freshman and sophomore at Boys Latin School of Baltimore he overcame strength-sapping Graves’ disease while enduring the murder of his grandmother by a cousin who molested him as a child.

“She was my main squeeze,” Featherstone said of his grandmother. “We shared the same birthdate — July 5.”

“Then came my 10th-grade year and the strength-sapping Graves’ disease. It’s a thyroid disorder which weakened me, caused shortness of breath and led me to lose 25 to 30 pounds during my sophomore year.”

Featherstone bounced back as a junior and senior to earn Maryland Interscholastic Athletic Association and Maryland Private Schools State titles, but he was “a struggling freshman” wrestler at The University of Oklahoma at the time of his father’s death.

“My dad was my wrestling coach and motivator throughout my life, and now he’s gone. There would be no more having him in my ear and giving me words of encouragement. At the time, I was the only freshman to start at OU. I wrestled two national champions in Troy Letters from Lehigh and Trent Paulson from Iowa State,” Featherstone said.

“I gave Paulson a run for his money, putting him on his back and losing by one point. I was offered a full ride to Virginia Tech and decided to transfer. But I tore my ACL riding a dirt bike three days before going to their campus in Blacksburg, Va., and never finished school. I joined the Marines for about three years before being granted an Other-Than-Honorable discharge for admitting that I smoked weed, even though I never had a positive drug test for it.”

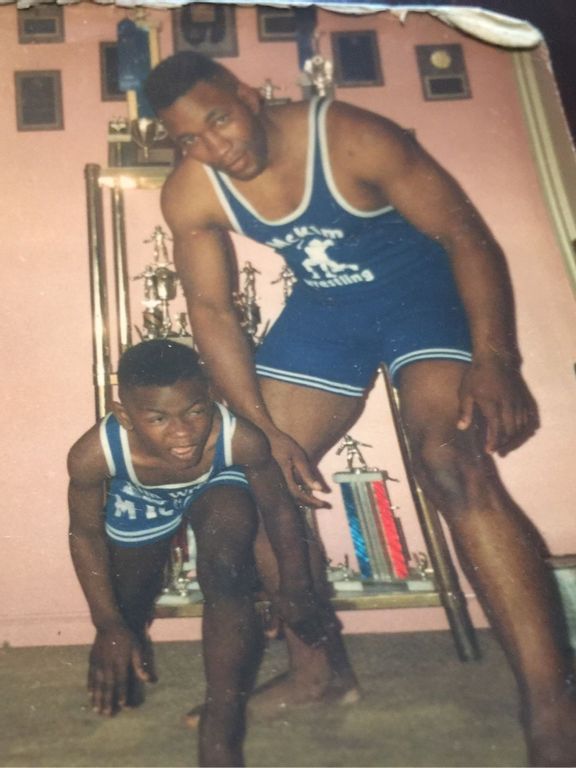

A local hero in Baltimore and a former Howard County deputy sheriff once named Deputy Sheriff of The Year, the elder Featherstone Sr. had spent three years in the Marines, 19 years married to his wife, Pamela, and several years steering black youth away from the streets as coach of the Mckim Center junior league wrestling program in Baltimore.

A 1979 graduate of Mervo High of Baltimore who twice placed third in the Maryland Scholastic Association tournament, Featherstone Sr. was awarded a posthumous Governor’s Citation in March 2004.

Featherstone decided to become like his father by giving back. He became a special education teacher at Baltimore’s Kennedy Krieger Institute and spent 2009 to 2016 working with autistic children.

Featherstone has also returned to Baltimore to assist Lydell Henry, who co-founded Beat The Streets Baltimore in 2011. That nonprofit runs primarily out of the Upton Boxing Club and uses wrestling, tutoring and mentoring to academically engage young student-athletes.

“I’ve been giving back with Lydell Henry and Beat The Streets. Like my Dad, I always try to help and encourage younger, less experienced individuals in wrestling, boxing, sports or life in general,” Featherstone said.

“When I lost my dad, I was devastated because he was my leader and my guide. I thought my world was over. But my dad always told me, ‘Son, don’t sell yourself short.’ So I’m honoring my dad by not settling for less. I have so much to live for with Amy and Jameson in my life. Through my dad, I truly see the importance of a male figure in a black man’s life.”

Edited by Matthew B. Hall and Kristen Butler

Recommended from our partners

The post Jerome Featherstone Jr. Fights On For Family Glory appeared first on Zenger News.