By Emily Zobel Marshall

Leeds Beckett University

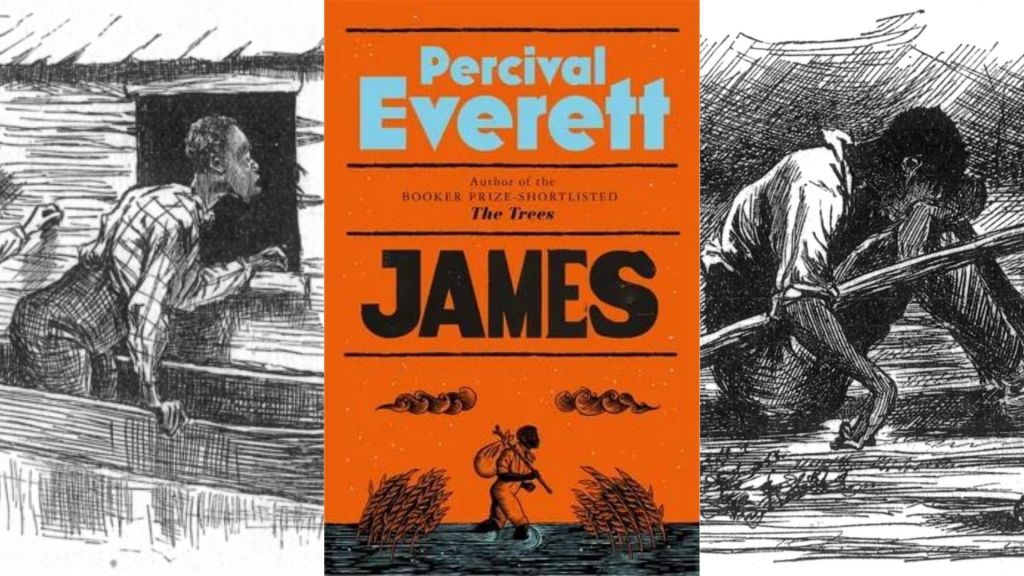

(The Conversation) – James, the new novel by Percival Everett, is a stunning book which I relished long after finishing. It is the sort of book you need to tell all your friends about – and you know once they have read it, it will fundamentally change them. They can never unlearn what they discover once they’ve walked in James’s footsteps.

James is an incredible re-writing of Mark Twain’s 1884 American classic The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn that tells the story from the perspective of the enslaved Jim. Just like the original book, it is set in the pre-Civil War plantation South. It’s 1861, war is brewing, and when the enslaved James hears that he may be sold to a new owner in New Orleans and separated from his family, he goes on the run as “Jim”, with the resourceful young white boy, Huck Finn.

The same characters appear in both texts, including Tom Sawyer (Huck’s best friend), the town judge and the duke and the king – con artists who take control of Huck and Jim’s raft. While the mischievous Huck is the main focus of Twain’s novel, James is centre stage in this story.

To escape his abusive father, Huck fakes his own death and goes on the run with James. James is a slave he thinks he knows well, a man subservient to him who he also considers his friend, but as Everett’s story unfolds, he realises he does not have the full measure of this remarkable person. Huck’s ingrained prejudices have led him to overlook James’s power and intellect, and James works very hard to conceal both.

Everett has reclaimed James from the peripheries and urges the reader to listen to his story. With James as our narrator, we hear about Huck and James’s adventures and near brushes with death and capture as they steer their makeshift raft down the great Mississippi River.

This is a literary, writerly and scholarly novel. Everett expertly weaves Black literary criticism and theory into his narrative, as well as making artful allusions to books that came before that have shaped American scholarly and literary traditions. This weaving, however, is done with a light touch.

Everett’s tale is gripping and deeply emotional. And his prose is as clear as a bell in this wonderful retelling of an American classic.

The shape-shifting trickster

Jim is, in many ways, a quintessential trickster figure. Tricksters like the spider Anansi and Brer Rabbit were the heroes of oral folktales brought from the African continent with enslaved populations.

Trickster tales focus on how the disempowered can turn the tables on the powerful using their brains rather than their muscle. The stories represent subversive strategies of survival and resistance enacted by the enslaved on plantations across the Americas.

The most remarkable aspect of the book is following the journey of James’s developing intellectual and political consciousness through his reading, writing and trickery. While on the run, he is able to source a pencil, with horrendous repercussions, and start to write his story.

James sneaks into libraries and steals books. He reads Voltaire, Rousseau and Locke. This education enables him to debate the ethics of enslavement and he has an impressive intellectual mastery of the English language, which he hides carefully from whites and even Huck himself.

James is a master code switcher, able to change the way he speaks to ingratiate himself to whoever he is speaking to. Before his escape he runs classes in his cabin for his enslaved children to teach them how to speak “slave speak” – to speak slowly, with a reduced vocabulary and to feign stupidity. This enables them to fool the slave masters while keeping their real language (and intelligence) hidden – to “play fool to catch wise”, as the Jamaican proverb goes.

These lessons are indispensable because, as James stresses: “safe movement through the world depended on mastery of language, fluency”. “Papa, why do we have to learn this?” the children ask. James explains that whites need to feel superior, or they will make the children suffer.

James displays the gifts of linguistic dexterity found in so many Black cultural forms, which were highlighted by the American literary critic Henry Louis Gates Jr. in his book The Signifyin’ Monkey (1988). Everett alludes to this Black literary and linguistic theory knowingly in the text – a sort of scholarly Easter egg for academic readers like me.

The book is being marketed as humorous, but I didn’t find it funny. There are slapstick moments, for example when their raft capsizes (which happens frequently), but these were mainly moments of fear and anxiety.

Instead, the tale elicits a deep empathy for Huck and James, through the complexity of their developing relationship and James’s self-emancipation. I was so completely invested in their story that nothing they faced on their gruelling journey seemed funny. I was simply immersed in rooting for them, and others will be too.

Read this book and listen carefully to James’s story. It will change you. You will start to question all the other classic novels you’ve read and wonder whose story is being suppressed and why. What if, you’ll ask yourself, they could be fleshed out and heard properly? It would, perhaps, be a much richer tale to tell.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent and nonprofit source of news, analysis and commentary from academic experts, under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article here: https://theconversation.com/james-by-percival-everett-an-enthralling-reimagining-of-huckleberry-finn-from-the-perspective-of-formerly-enslaved-jim-228940

The post James by Percival Everett: an enthralling reimagining of Huckleberry Finn from the perspective of formerly enslaved Jim appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers.