An invasive ant may have met its match in a naturally occurring fungus that can destroy it from the inside out.

The crazy ant (Nylanderia fulva), sometimes called the “raspberry ant” in Texas, is originally from Argentina. It is dubbed “crazy” because of its quick, unpredictable movements.

The tawny-colored ants are reportedly overwhelming populations of fire ants — known for having a venomous bite — because of their ability to detoxify the fire ants’ venom.

They measure about 1/8 of an inch. Related species are found across the world, except in cold climates and central and northern Europe.

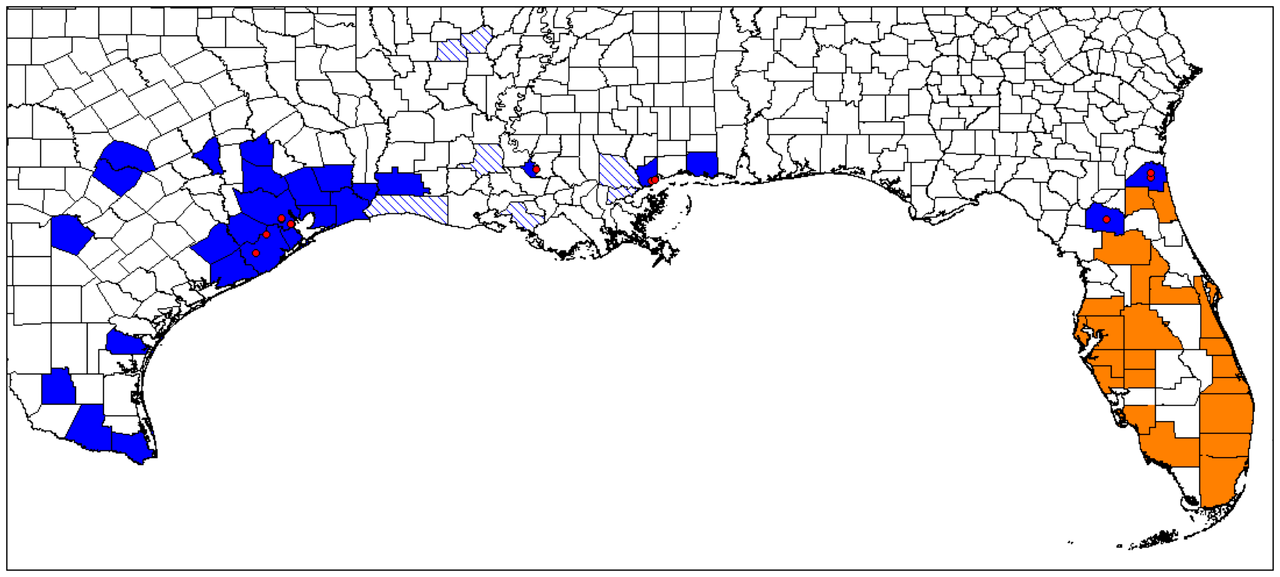

Spreading in the southeastern U.S. states, they are also driving out various native insects and small animals.

In Colombia, where they have displaced other ants, they kill poultry by asphyxiating them and attack cattle by infesting their eyes and nostrils. They forage for plants and tend tiny aphids in underground galleries to feed on the honeydew these creatures excrete, drying out grasslands as a result. Baby rabbits have also been blinded by these ants.

The ants are not attracted to ant baits currently in use and are immune to over-the-counter pesticides. Their colonies are hard to exterminate because of their multiple queens. In 2008, the Environmental Protection Agency approved the temporary use of fipronil, a moderately toxic pesticide that is very toxic to rabbits, in an exemption that expires on May 6, 2022.

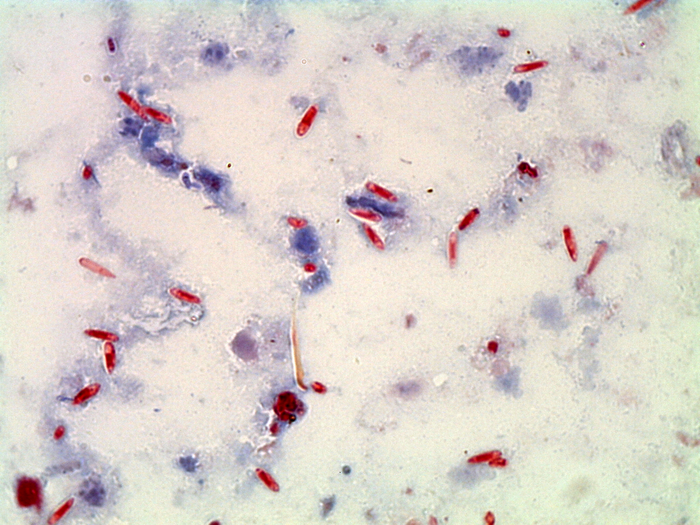

However, a study appearing in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences indicates that a group of fungal pathogens previously unknown to science may serve to control the spread of crazy ants. These microsporidian pathogens hijack the ants’ fat cells, turning them to the production of spores.

“I think it has a lot of potential for the protection of sensitive habitats with endangered species or areas of high conservation value,” said researcher and lead author Edward LeBrun of the Brackenridge Field Laboratory at the University of Texas.

Scientists had noticed that wild populations of crazy ants had become infected by the fungus and collapsed without human intervention.

The stakes are high not only for farmers and ranchers but also for homes and businesses. Crazy ants swarm into electrical circuits, breaker boxes, air conditioners and other electrical devices, causing short circuits.

Study co-author Rob Plowes collaborated with LeBrun on a study of the ants in Florida in 2005. They observed crazy ants with abdomens swollen with fat and found microsporidian spores in them. The pathogen may have come from the ants’ native habitat in South America. Since then, the researchers found that every infected colony declined, with 62 percent dying out completely.

“You don’t expect a pathogen to lead to the extinction of a population,” Le Brun said. “An infected population normally goes through boom-and-bust cycles as the frequency of infection waxes and wanes.”

LeBrun believes that the pathogen shortens the lifespan of worker ants, making it harder for a colony to survive during cooler months.

However, microsporidia do not appear to harm native ants and other arthropods, potentially making the pathogen ideal as a biological control.

In 2016, LeBrun and his colleagues used microsporidia on an experimental basis at Estero Llano Grande State Park in Texas, which was losing native reptiles, birds, insects and scorpions to the invasive ants. “They had a crazy ant infestation, and it was apocalyptic — rivers of ants going up and down every tree,” LeBrun said.

After placing infected ants in nest boxes in the park, the team baited the ants with hot dogs at the entrances of established colonies. Once the introduced ants and locals were merged, the disease spread throughout the colonies. In just two years, the number of crazy ants plummeted at the park.

Crazy ants have since been eradicated at the site, allowing native ants to re-establish a presence. The research team has also been able to eliminate a second population near Convict Hill in Austin, Texas.

Crazy ants bite but do not sting. They excrete formic acid from their abdomen as venom, in what is believed to be an adaptation to ward off fire ants. Meanwhile, fire ants have alkaloid-based venom that paralyzes competitor species, but this is neutralized by crazy ants’ formic acid antidote.

“This doesn’t mean crazy ants will disappear,” LeBrun said. “It’s impossible to predict how long it will take for the lightning bolt to strike and the pathogen to infect any one crazy ant population. But it’s a big relief because it means these populations appear to have a lifespan.”

LeBrun and his team will test this biocontrol approach elsewhere in Texas later this year.

Edited by Siân Speakman and Kristen Butler

Recommended from our partners

The post Invasive Crazy Ants May Be Defeated By Microscopic Spore appeared first on Zenger News.