By Joseph D. Bryant and Hannah Denham

The scheme was complicated, with piles of tax money flowing from Jefferson County to a youth baseball league, then to a dance team, which prosecutors say never performed, and finally into personal bank accounts, credit cards and mortgage payments.

That’s according to the case made by federal prosecutors, who reference three key people behind the recent scandal. But so far the prosecutors have charged only one with a crime. Fred Plump last month resigned his seat in the state legislature and pleaded guilty to federal charges of conspiracy and obstruction of justice. He’s scheduled to appear in federal court in Birmingham later this month for sentencing.

Now, the details in Plump’s plea agreement, as well as AL.com interviews with some of those involved, make clear how it all allegedly worked.

The plea agreement, which Plump signed on May 18, references two other figures involved in the kickback scheme — “Legislator #1″ and “Individual #1″ — but doesn’t identify them by name.

The other legislator mentioned in the plea agreement is Rep. John Rogers, who identified himself to AL.com as “Legislator #1″ when federal prosecutors announced the charges against Plump. Prosecutors assert, and Plump said in his plea agreement, that the legislator directed tax money to Plump’s baseball league as “part of the conspiracy.”

Rogers has repeatedly told AL.com that he did nothing wrong and got no money.

The third figure, listed in the plea agreement as “Individual #1,” is a legislative aide to Rogers. Rogers identified her as his longtime privately employed assistant, Varrie Johnson.

“I trust her, and whatever Fred and her did, that’s their business. I don’t know anything about it,” Rogers, D-Birmingham, told AL.com. “He’s supposed to do what he’s supposed to do with it. If he doesn’t, then he’s in trouble. I guarantee you I haven’t done a damn thing.”

Johnson has not been charged with wrongdoing. She did not return calls or respond to messages from AL.com for this article.

Richard Jaffe, the Birmingham attorney representing Plump in the federal case, said he does not dispute that Johnson is “Individual #1″ as listed in the plea agreement. AL.com also confirmed that Johnson is “Individual #1″ in interviews with three other sources.

While she is not listed as a legislative employee in state records, Rogers told AL.com he employs Johnson and pays her privately to assist him with both public and private matters.

“She handles all my affairs, my care and everything,” Rogers said. “I pay her. The state does not pay her.”

Rogers said that sometimes when he is busy or unavailable, he has Johnson handle his legislative business, such as signing his name on paperwork. The 82-year-old legislator said he suffers from hip problems and that Johnson is also his “caretaker,” driving him around and helping with daily tasks.

“She is working for me,” Rogers said. “I let her sign my name. I give her permission.”

Rogers said he has never misused public money.

Plump, a Democrat from Birmingham and longtime youth sports coach, won office in 2022 to serve in the Alabama House of Representatives.

Federal court records now say Plump, starting about three years before he took office, conspired to defraud and obtain money by moving public dollars through his nonprofit and kicking back a portion. The financial dealings began in March 2019 and continued through April 2023, according to Plump’s plea agreement.

The money came from something called the Jefferson County Community Service Fund, a pool of tax money to support local causes. The fund was created by the state legislature in 2015 to allow the Jefferson County Commission to collect a 1 percent sales tax and use tax, so local legislators could dole out about $3.6 million annually to schools, libraries, police departments and youth sports. The fund began giving out grants in 2018. Once a legislator recommends that a group receive funding, a committee reviews and approves the grant.

Here’s how the kickback scheme worked, per Plump’s plea agreement: Legislator #1, whom Rogers identified as himself, recommended that the fund send money to Plump’s baseball league. Plump then submitted falsified budgets to the fund’s committee, and, once approved by the committee, Legislator #1′s assistant delivered the checks from the fund to Plump.

Then, according to the plea agreement, Plump wrote a new check for half of the money from his baseball league to the assistant, whom Rogers identified as Johnson. Typically the checks noted that they were for a “dance team” or “cheerleading,” according to the plea agreement. But the assistant did not provide dancers or cheerleaders for league events, and Plump knew she didn’t need money for a dance team, his agreement states.

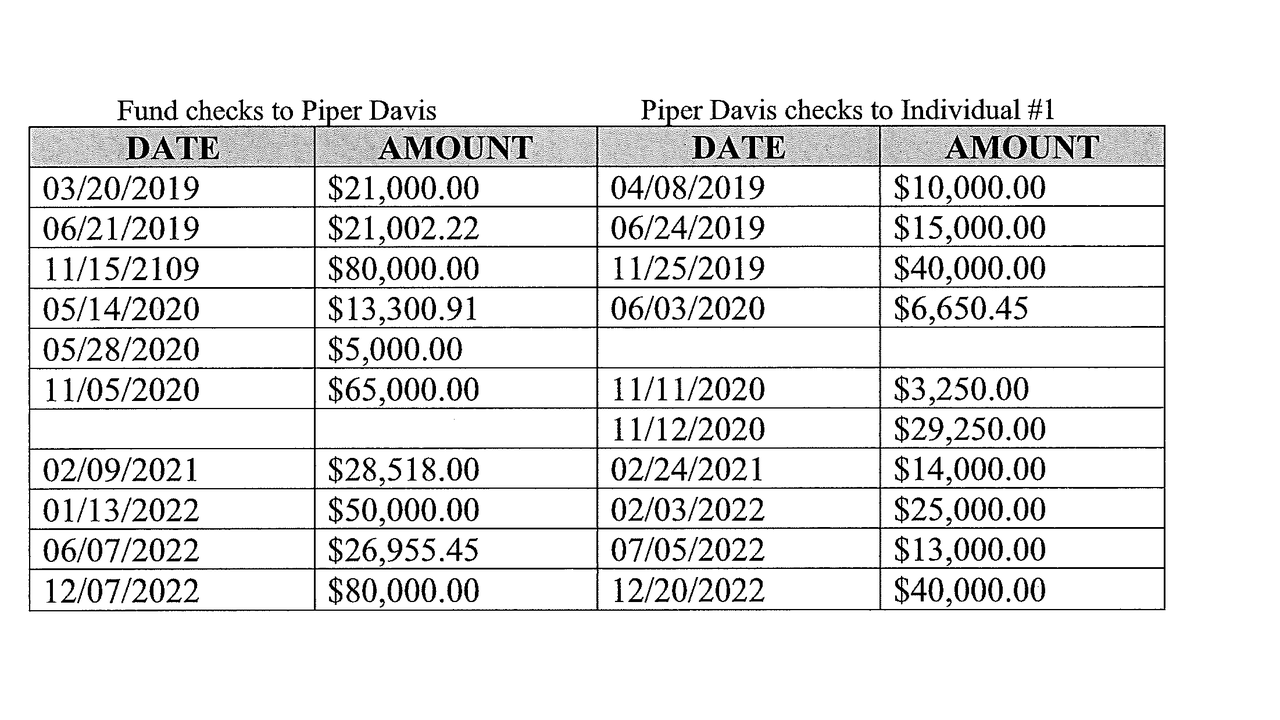

In total, Plump wrote 10 checks to the assistant, totaling more than $196,000, according to the plea agreement. The assistant deposited the checks from Plump’s baseball league, called Piper Davis, into personal accounts and used the money for cash spending as well as mortgage and credit card payments, the plea agreement states.

The plea agreement also says Legislator #1, whom Rogers identified as himself, was to receive a cut of the money.

“When the Committee issued the check to Piper Davis, Individual #1 delivered the check to Plump and Plump wrote a check to Individual #1,” the plea agreement reads. “Individual #1 told Plump that they needed half, meaning Plump was to give half of the Fund money to Legislator #1 and Individual #1.”

“Plump agreed to pay kickbacks from fund money directed to Piper Davis by Legislator #1,” the plea agreement continues. “Plump understood that if he did not give half of the money to them, Legislator #1 would not direct fund money to Piper Davis.”

Rogers recommended roughly 80 percent of his allocations from the community service fund go to Plump’s baseball league, according to the community service fund’s records. He did so on forms that required him to certify he hadn’t asked for “anything of value” in exchange for the recommendation and that the funds’ use would qualify under its legislated purposes.

Rogers allocated $497,000 since 2018 and of that, nearly $386,000 went to Plump’s baseball league, per the fund’s records. After the first year of the fund’s disbursements, he only allocated to a few other recipients, Hoover High School, the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame and the Birmingham Urban League.

“It was part of the conspiracy that Legislator #1 would and did recommend during each fiscal year that most of his allotment of fund money be paid to Piper Davis,” the plea agreement states.

Jaffe said his client, Plump, did not personally benefit from the misuse of the grant money.

“I’ve read several accounts that Coach Plump personally benefited from some of these proceeds by putting them into his personal accounts and that’s completely untrue and false,” Jaffe told AL.com. “All of the money that he received other than what he unlawfully paid for a dance program he should have known did not exist went into the Piper Davis 501c3 charity for the benefit of minority youth through baseball programs. He did not personally profit a dime and all accounts that say otherwise are wrong.”

With his guilty plea to federal charges of conspiracy and obstruction of justice, Plump faces up to 20 years in federal prison, plus a fine of as much as $250,000 for each of the two charges. Plump agreed to pay back at least $200,000 to the Jefferson County Community Services Fund as part of the plea agreement.

As far as broader questions about the scheme, a spokesperson for the U.S. Attorney in Birmingham did not respond to a request for comment.

As for the employment arrangement between Rogers and Johnson, legal and ethics experts told AL.com that mixing personal and professional ties presents ethical concerns.

Jim Sumner, the retired longtime director of the Alabama Ethics Commission, said that private employees should not conduct public business because they cannot be held accountable in the way government workers are.

“That would concern me greatly, because you would think the public official would want someone who was accountable to the public to be the person who was acting at their behest,” Sumner told AL.com.

He said it is not unheard of for public officials to have their assistants act on their behalf or even sign on behalf of the official. But it raises ethical concerns, he said, when those assistants are not public employees covered by ethics laws.

At the Statehouse, most legislators usually share assistants among a pool of clerks that are publicly employed by the state. But Rogers said he has employed Johnson privately for many years, paying her with his own money to handle both legislative and personal business.

Susan Pace Hamill, a professor of law at the University of Alabama, said there is nothing wrong with a legislator hiring a personal valet, under the proper conditions. Problems arise when state money is misused to fund personal needs, she said.

“If Rep. Rogers is really using his own money, the money he earned from his salary as a state legislator or legitimate business on the side, and some of that money is being used to pay for this help, I don’t have a problem with that,” said Hamill, a former legislative candidate whose legal focus includes ethics. “Politicians have access to funds that aren’t technically part of the state payroll but have restrictions on how to use it.”