By Rebecca Griesbach

Rebecca Griesbach

In Mary Gaston’s classroom, Tuscaloosa high schoolers spent a Wednesday afternoon preparing a list of questions for the sister of a late local activist.

“Did you ever not want to be Black?” one Northridge High School student scrawled onto the whiteboard.

The question joined other inquiries about Black women’s role in the Civil Rights movement. Students wanted to know whether Bettye Rogers Maye had ever feared for her own safety after her brother was targeted by Klansmen in the 1960s.

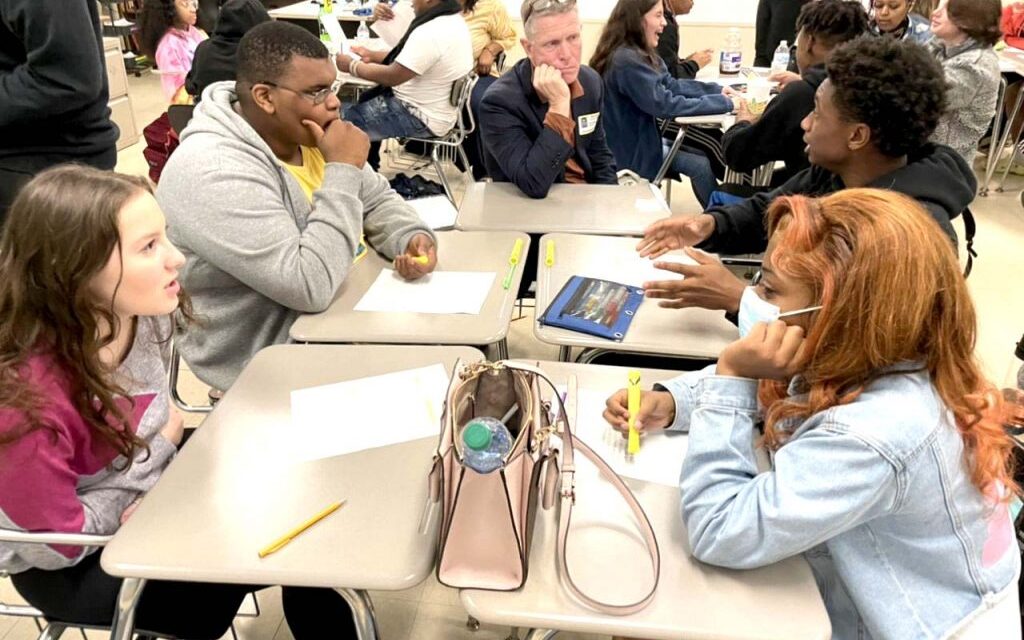

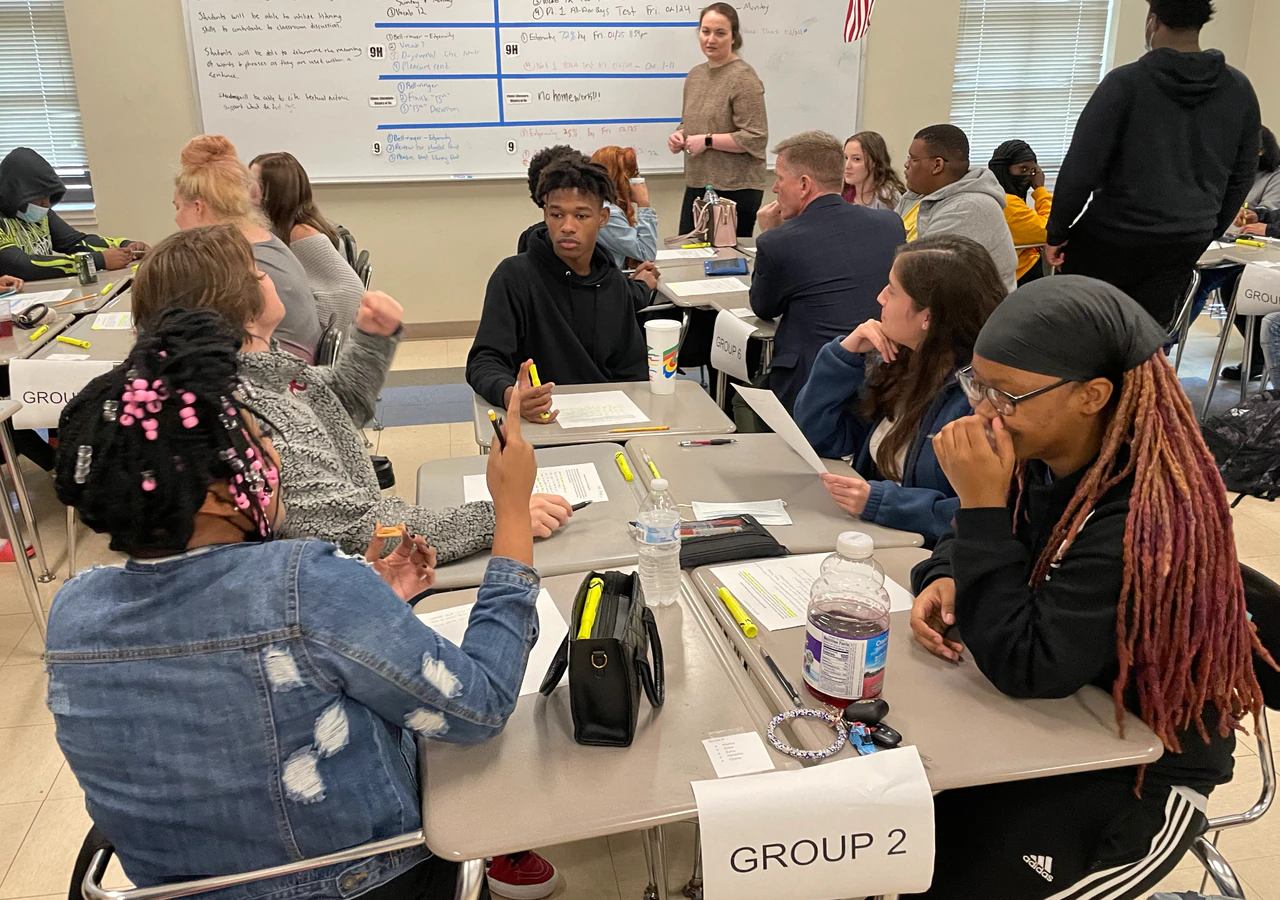

They gathered in groups to prep for an interview with Maye, the sister of the late Rev. T.Y. Rogers, who helped organize a march to protest segregated drinking fountains and restrooms at the Tuscaloosa County Courthouse in 1964.

“And that march turned into what?” Gaston asked the class.

“Bloody Tuesday,” the students chimed in, referring to the mass arrests and police and mob violence against Rogers and other Tuscaloosa protestors. In the same class, Gaston’s students wrote about how they would feel if they had to drink from separate water fountains in Tuscaloosa – an instructional format that experts say helps students connect feelings to historical terms.

Gaston’s class is one of few in-depth Black history courses offered in Alabama public schools, according to educators. A Huntsville school offers a year-round Advanced Placement research course, and some districts offer summer Freedom Schools for younger students. Other schools offer units or lessons about Black history in the state and in the country, but experts say year-round courses can provide children more space to explore history from varying perspectives.

The class, “History of Us,” began in 2019 at Central High School, where University of Alabama Associate Professor John Giggie and graduate student Margaret Lawson taught students key research skills and explored topics connected to local African American history. District leaders expanded the course this year.

Now, about a hundred students across the district’s three high schools are enrolled in the elective, and creators say it could prove to be a model for the rest of the state.

“A great history class does more than simply teach students,” Giggie said. “A good history class will help people think about the world differently. But a great one will help them live in it differently.”

In Gaston’s class, a mix of students said they felt the course had unified them in a way that wouldn’t normally happen in the hallways, the lunchroom or in core classes.

“It brings everybody together,” said senior JonTavious Peoples, who said his natural curiosity led him to enroll in the course. When approaching difficult topics, he said, he trusts his classmates to “talk it out with each other.”

Sophomore Anna Ryn McNiel recalled a lesson where the class made a T-chart on the board and listed words that came to mind for “American History” and “Black History.” She said some of the words her classmates had listed under “American History” were more negative than her own, which made her rethink her perspective.

But the lesson didn’t divide the students, she said. Instead, she felt a call to action.

“I was like, ‘We need to do better,’” she said.

A local approach

Across the country, at least 17 states have introduced legislation requiring more courses on racism, bias and the history of specific racial or ethnic groups. Alabama isn’t one of them.

In fact, legislators are considering a bill that would restrict teaching on race, gender and religion and might, some educators fear, hinder efforts to teach an honest account of the past.

Giggie said the course he developed for Tuscaloosa schools hasn’t received pushback from parents. Creators took care to examine both the “triumphs and the shortcomings” of U.S. history, “not in a way to create blame or to avoid responsibility, but to offer an honest assessment,” he said.

“I think this is exactly the kind of class they want,” he said, referring to state legislators. “It’s a mix of that which represents the very best of American democracy, and then that which asks us, ‘How can we do things differently and better?’”

In Tuscaloosa, creators of “History of Us” say support from the district is key to success. As the course expanded, each school designated its own teachers to lead the classes. Some teachers, such as Bryant’s Katorrie Babatunde, teach up to three sections of the elective, while others continue to teach core subjects.

Throughout the year, students interview their relatives about key moments in history. They learn how the churches they attend and the streets they cross to get to school were integral to the Civil Rights movement.

Students also learn contemporary history. Giggie and Lawson have compiled a drive of curricular materials that teachers can pull from. One of those texts is “Segregation Now,” a ProPublica investigation of the resegregation of the Tuscaloosa City school system in the early 2000s.

Northridge is located on the north side of the Black Warrior River, among some of the city’s whitest and wealthiest neighborhoods. The school, in contrast to majority-Black Central and Bryant high schools, is about 55% white.

In Gaston’s class, instructional coach Lakesha Tillman assisted students with group work, while Giggie dropped in to observe.

But no matter the resources and personnel a school has, local history lessons can easily be incorporated into classroom lessons, experts say.

“Teachers are already doing a version of this,” said Giggie, who is working with college students to design lesson plans and curriculum guides that they hope to share with other districts. “They’re using their local landscape. They’re using student’s lives, to intrigue them of questions of historical change and continuity.”

“What I hear again and again is, ‘Tell me more about me. Oh, how was my story important? How does it connect to history?’” he added. “And that’s not something wedged in Tuscaloosa. It’s a universal request that I hear from students across the state.”

Place-based lessons, experts say, can help improve student engagement and bolster skills like communication and critical thinking.

For Northridge tenth grader Mia Walker-Samuel, the course allowed her to “connect the dots” with her own family. When she learned about the legacy of Rev. Rogers, she said, she thought about her own grandfather, who was a local preacher, and wondered whether they knew each other.

“Honestly, I thought I knew enough [of Black history], but I was wrong,” she said. “Seeing that people in Tuscaloosa actually did care and had involvement in the Civil Rights movement – I honestly thought we didn’t do anything good here.”

Tenth grader Natasha Sandoval moved to Tuscaloosa three years ago. She often shares what she learns about the community’s history with her younger siblings.

“It gives them an insight to see how people of color have been treated here… which everyone should have the right to know,” she said.

Local leaders

An emphasis on local history can also produce local leaders, Giggie said – students who are invested in their communities and want to be a part in how they tell their ongoing stories.

One of those students is Alex Barnes, a Central High graduate and current freshman at the University of Alabama who enrolled in the pilot course in 2019. He’s now studying the impact of Black businesses in the state, and he’s continuing a project on lynching that he started in Central’s course.

Nearly every student enrolled in the course at Central attended college, Giggie said. For Barnes, having access to college professors was a factor that swayed him toward higher education.

The course at Central, he said, taught him specific research skills that he uses in class every day. And engaging with primary sources and local events, he said, renewed his interest in history.

“Although it could be depressing at times, I don’t regret learning about it,” he said. “I don’t want to be kept in the dark.”

Barnes said he hopes the course can expand and include younger grades and potentially include college credit. Walker-Samuel said she looks forward to learning more about mass incarceration.

Sandoval said she hopes the course will pave a way for her to learn more about her culture, too.

“There’s not much that I know about other than the Chicano movement,” she said. “But I wonder if there was anything like that to happen in Tuscaloosa at the same time.”