Years after brothers serve 20 years for rape they said they did not commit, judge tosses wrongful conviction

This is an opinion column.

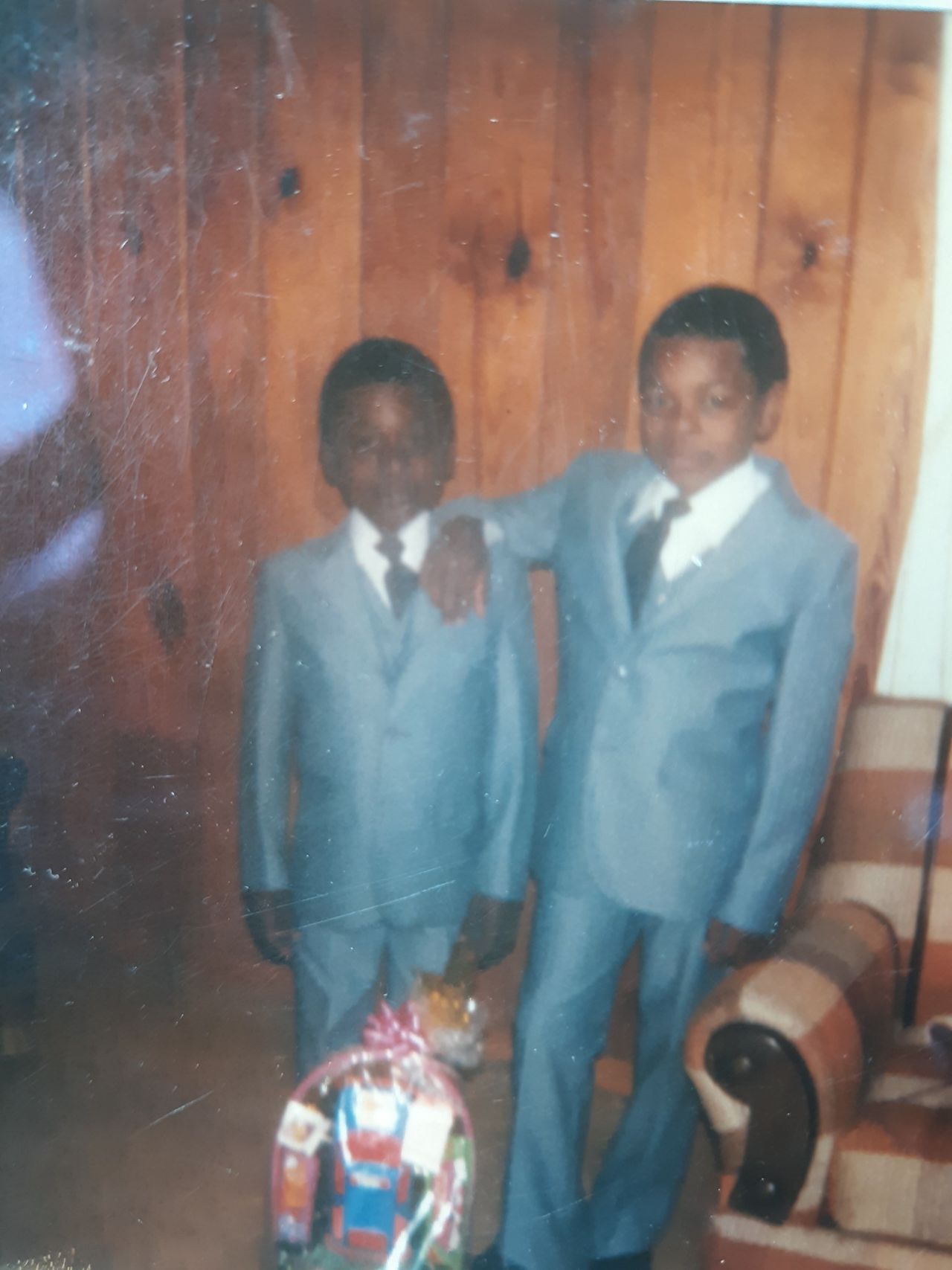

Frank Meadows, Jr. may never wear sneakers again. He and his older brother Quinton Cook can laugh about it now. They can laugh about something as inconsequential as footwear and what they’ll wear to church.

They can laugh about it now because of the consequential weight recently lifted from their lives when Jefferson County Circuit Judge Shanta’ Owens ruled last month that the two men were wrongfully convicted of rape in 1993, a crime the two men always declared they did not commit. A crime for which each served two decades in prison.

In her orders, rendered on Oct. 25 in response to a Rule 32 petition for postconviction relief, Owens noted her decision was based on the discovery of an “original” Leeds Police Department report containing “exculpatory information that establishes [their] actual innocence”, including the “original statement given by [the victim] to the police in which she said two men from Pell City attacked her and that one of the men was named ‘Ray’.”

In addition, Owens noted: “The report revealed additional blood evidence that was present at the scene and never tested.”

“The evidence was suppressed by the State and not provided to the defense counsel,” her order states. “Nor was it presented or utilized at trial. This exculpatory information was shielded from [Meadows and Cook] and [their] counsel, thus prejudicing [their] right to a fair trial.”

“This court orders that [their] Rule 32 Petition for Postconviction Relief be GRANTED and that [their] conviction and sentence be vacated and set aside due to wrongful conviction.”

Our judicial system often gets it right, eventually—too often, though, long after the system got it egregiously wrong. In between, people pay dearly. With portions of their lives that cannot be relived.

Cook was 21 years old when he began serving 20 years that cannot be relived—20 years that ended in July 2014. “EOS (end of sentence): Seven, fourteen, twenty-fourteen,” he says with an emphatic tone, recounting a date all previously incarcerated individuals likely know by heart.

Cook is 50 now and recalls hearing Judge Owens’ ruling as “a surreal moment for me.”

“I just burst out into tears in the courtroom,” the older brother told me. “When I left in court, my mind was all over the place. I was happy. I was excited. I was overjoyed. I was trying to find ways to just spread the word because I’ve been living with this for so long, and somebody finally saw the truth. All these people that didn’t know whether we did it or not or believed we did do it, I just wanted to say, ‘Hey, man, I told y’all I didn’t do this.’”

Meadows, now 48, was just 19 when he was incarcerated. He reached EOS the May after his brother. “Five, five, twenty-fifteen,” he tells me.

He talks of living with the specter of being a convicted rapist, and upon release, a registered sex offender for more than half of his life—years that cannot be relived.

For both men, the ruling meant a new kind of freedom.

“When you’ve lived with it for so long, and you’ve been set free, I began to just thank God and praise God,” Meadows says. “I began to realize I was actually free. There’s stuff I can do now that I used to couldn’t do, places I can go that I couldn’t go. I’d been in a box for so long, it’s sort of like turning the lights on—been in the dark so long, it hurts your eyes. When you live in that type of shame, you now want the world to know, ‘Hey, I didn’t do it.’ I can actually talk about it now. I’m still excited. I’m walking in it every day.”

‘I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Cook and Meadows grew up in Trussville, the “poor part of Trussville,” they recall, “the Black part.” Their parents—Frank Meadows, Sr., and Augusta—filled their home with faith, attending a Baptist church before joining Soul’s Harbor Deliverance Center in Norwood. “We got the Baptist and the holiness experience,” Cook shared with a laugh.

On the day he was arrested, Meadows was on his way to pick up his girlfriend at work. He pulled over at a gas station, filled up, then walked into the convenience store. “For a pack of cigarettes,” he recalls. “I came out and [police] had my car surrounded and guns drawn. They made me get on the ground with a knee all in my back. I’m saying. ‘Man, what’s going on? What’s the problem? What’s going on?’”

He was Mirandized and handcuffed, then heard the charge was first-degree rape. “I’m telling [the officer], ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about,’ Meadows says. “He said, ‘If you don’t know what we’re talking about, you can help yourself out.’ I’m like, ‘How can I help myself when I don’t know what you’re talking about?’.”

Their parents could not afford bail, but both men say they then “believed” in the judicial system—naively so, they now know.

Cook and Meadows remained in county jail for nearly a year until their trial. Because of their innocence, they were not worried, especially after hair and saliva samples were taken. “I was happy when that happened,” Meadows recalls. “I felt like, ‘I’m gonna get to go home once these results come back.’”

What the two young men and their counsel did not know was that there was an initial police report taken by a first responder at the scene in which the victim is recorded saying one of the two men who attacked her was named “Ray”. They did not know the report was squashed in favor of a second one where she named Meadows and Cook. [The victim is now deceased, as noted in Judge Owens’ order.]

“I still was believing in the system and that when we made our first court appearance, the truth was going to come out,” Meadows said. “Whoever this girl is, I’ve never seen her before in my life. So, when she sees me, she’s gonna tell you I didn’t do it and you’re gonna let me go home.”

That did not happen, sadly. The victim named Cook and Meadows as her attackers. “She described me as tall and slim,” Meadows says. “I’m 5-8 and at the time I was over 300 pounds. I’ve never been tall, nor slim.”

Both men say they sat shocked in the courtroom as the victim spoke on the stand. “I didn’t know what to do,” Meadows says. “I’m telling my lawyer she’s lying and he’s telling me, ‘Be quiet, be quiet.’ The judge says, ‘Y’all need to get them under control.’

“When you ain’t did it and you don’t know nothing about the system, you believe them when they tell you you’ve got nothing to worry about. I believed them, and it cost us. Young Black men, we didn’t know nothing about the law, about the court system. We believed the system worked.”

It did work—against them.

When the guilty verdicts were read, back in December 1993, Augusta fainted, Meadows recalls. As the guards took him and his brother back to jail, he became emotional. “I began to holler and scream, ‘Hey that’s my mom,’” he remembers. “They kept telling me to calm down, but I didn’t know if she died or what happened. All I knew is she just hit the floor and my dad is trying to pick her up while they’re rushing me back. That was one of the hardest moments in my life. It crushed me.

“When I used to call home [while incarcerated],” Meadows continued, “and my mom would say, ‘How you doing?’ The first thing I said was, ‘Hey, you alright? Because of you alright, I’m gonna be alright. If you’re okay, I’m gonna make it through.”

That mother’s bond with her sons, anchored by their faith, indeed got them through—through decades that can’t be relived.

Both men served their time at various institutions around the state, institutions declared incorrigible—declared unconstitutional, by the U.S. Department of Justice. Sometimes they were together, sometimes apart. They recall especially the horrific introduction to the penal system at Kilby Correctional, just outside of Montgomery, a “receiving center” that intakes all the newly incarcerated, except those sentenced to death or youth offenders.

“You got to grow up real fast when you walk through those gates, man,” Meadows recalls. “Their job is to impart fear. Before they send you to a different prison, they want to know what type of person you are. Their job is to provoke you. We was raised to be humble and respectful, so I’m thinking, ‘As long as I’m respectful, I’m okay.’ But in that place, respect didn’t matter. They’re trying to see if you’ll flare up. Do we need to send you to a higher level of security?

“Then you have to learn how to live inside the prison, especially with [our conviction]. The only thing worse in prison than a rapist is a child molester. When [our conviction] surfaced and gets around to other inmates and officers and guards—and I’m just being honest here—you get classified as a sicko. I’m like, ‘Hey, man, I didn’t even do it,’ but nobody hears you.”

While incarcerated, Cook earned his GED and gained an associate degree in business “and a couple of Bible study degrees,” he says. He also learned barbering, upholstery, and brick masonry and now runs a wrecker service.

Meadows learned plumbing and masonry “and spent ninety percent of y time studying the Bible,” he says. “I read it relentlessly every day, fasting and trusting God.”

In 2012, three years before reaching EOS, Meadows married his long-time girlfriend. “I thank God for her,” he says, “for helping me navigate through financially. Having a wife that’s with you makes a whole lot of difference.”

He has three stepsons—from high-school age to 22 years old. He talks fondly of “raising them boys who they don’t get caught up—just talking them through life.”

It was all the harder because they were not able to live as a family due to Meadows’ sex-offender status, which didn’t allow him to live under the same roof as children. Instead, he lived with a family friend in Trussville. Meadows visited his wife’s home, could stay for hours, but he would leave before sundown. “It’s hard trying to raise three teenage boys when you can’t be there all the time,” he says.

‘They never let up the fight’

Rule 32 petitions for postconviction relief are rarely successful. They’re most often filed, when they’re filed, by one of the large non-profits, like the Equal Justice Initiative or Alabama Appleseed Center for Law and Justice. By groups seeking to right the wrongs of our justice system. Or by a private firm, after most likely having been turned down elsewhere. Fewer than one in 10 Rule 32 requests are granted, many estimate.

Birmingham attorney Leroy Maxwell, who represented Meadows and Cooks, says his firm’s batting average is closer to one in five.

One unique pearl in his clients’ quixotic quest to prove their innocence was that they were no longer incarcerated. “Once [the convicted] are out of prison, we don’t often hear from them again,” says Maxwell. “They don’t want anything to do with the court system or the state of Alabama.

“[Meadows and Cook],” he added, “never let up on the fight.” Soon after reaching EOS, indeed, Cook began donning shirts and caps emblazoned with “wrongfully convicted”.

That the exculpatory police evidence found its way to Meadows and Cook was happenstance—or a reward for their faith. Cook became involved in “another incident” unrelated to the rape conviction, Maxwell says. Seeking information about it, Cook’s wife Sharon, went to the Leeds police department and asked for everything related to him.

Among the files was the squashed report.

She gave it to Cook, who read it and shared it with Meadows. “When I read it for the first time, I was so emotional,” Meadows says. “It wasn’t so much anger because I wanted to be free. I’m seeing something with someone saying somebody else did it. I wanted somebody to see this.”

Meadows all but ran to the office of Jefferson County District Attorney Danny Carr but didn’t see him and was advised, for legal reasons, to take the report to the office of Jefferson County Sheriff Mark Pettway. Once there, Pettway asked then-deputy Wendell Major to look into it. Two days later, Meadows says, he was called back to Pettway’s office.

Meadows recalls: “[Pettway] said, ‘I wasn’t the sheriff then, but I’m the sheriff now and I just want to apologize for the injustice that was done.’’

Maxwell was subsequently hired; the brothers split $200 monthly until the fee was fully paid. The attorney says he was “heartbroken” upon seeing the report.

“It’s not often you have evidence in hand that could turn the tide,” he says. “Usually, you have to connect the dots and reconstruct evidence. I thought, ‘This can’t be true. How could it be something the defense was never made aware of?’”

The file also contained reports from the county’s Department of Forensic Science stating it did a DNA analysis of Meadows’ and Cook’s hair and saliva samples and “found no DNA match whatsoever,” Maxwell says. “I was shocked. There was a statement saying the attackers were 6-2 and thin, and neither of these guys are. The report clearly states blood was splattered at the scene, but never collected. So not only did it not get to the defense, but it never got to the Department of Forensic Science.

“And when we learned [after Major’s investigation] that law enforcement was actually involved, I thought we might have something here—actual innocence.”

During the hearings before Judge Owens, Meadows testified about their mother’s faith and how it girded her two boys through years that can never be relived.

“She implanted God in us at an early age,” he told me. “My prayer was for God let [our parents] live to see us get out of prison, let them live to see us clear our names. That day, I looked at her and broke down That was my drive.”

Frank Meadows, Sr. will soon be 73 years old; Augusta will soon be 72.

Attorney ‘can imagine a civil rights lawsuit”

At the time of the convictions, David Barber was Jefferson County DA. Carr says his office will file a motion this week to dismiss the case. “We don’t plan on retrying it,” he says.

The final hurdle should be cleared on November 14 when Meadows and Cook are once again scheduled to appear before Judge Owens, where she will rule that their convictions have been set aside with prejudice, meaning they cannot ever again be brought before the court.

Meadows says the brothers will file a claim under Alabama’s wrongful incarceration statute, which allows for $50,000 for each year wrongfully served. That’s $1 million for each man.

Though that may not seem like enough—for years that cannot be relived. Maxwell says he “can imagine a civil rights lawsuit coming down the pipeline” based on Brady v. Maryland, the 1963 precedent-establishing case that ruled the government must turn over any evidence that may exonerate a defendant.

May exonerate men like Meadows and Cook.

Intriguingly, the two men are finally free from a system that initially betrayed them and are eager to address today’s violence among youth and adults. “Adults need to be mentored, too,” Cook says. Last December, he conceived a proposal to launch an effort called THUGS. “I know how it sounds,” he says with a laugh. “It means Together Helping Us Grow Stronger. We’re flipping the word. It’s a catchy name that may attract some young people—the generation coming up now. If we can get through to them… We have to go back to our faith, to what brought us through.”

The two men were talking about going to church. Meadows talked about the two-piece suit and dress shoes he was looking forward to wearing. That the church they would attend allowed casual attire was of no matter.

“I may never wear sneakers again,” he said.

“We got educated in [prison], “Cook says, “but mainly more spiritual. God’s hand was in control during the whole situation. If not, who knows what our lives would be? He navigated us through and brought us back home.”

Back home and living new lives.