When Lauren Smith was a kid, her uncle gave her a gift that would impact her – and her future classroom – for years to come.

It was a copy of Alex Haley’s “Roots,” a 1976 novel tracing the fictional life of Kunta Kinte, an 18th century African captured into slavery, and his African American descendants.

“I think what I took from that, is that history really does follow linear lines, because Roots follows a family,” she said. “That linear story is something that I can use for every class to make them kind of know where we are in the picture.”

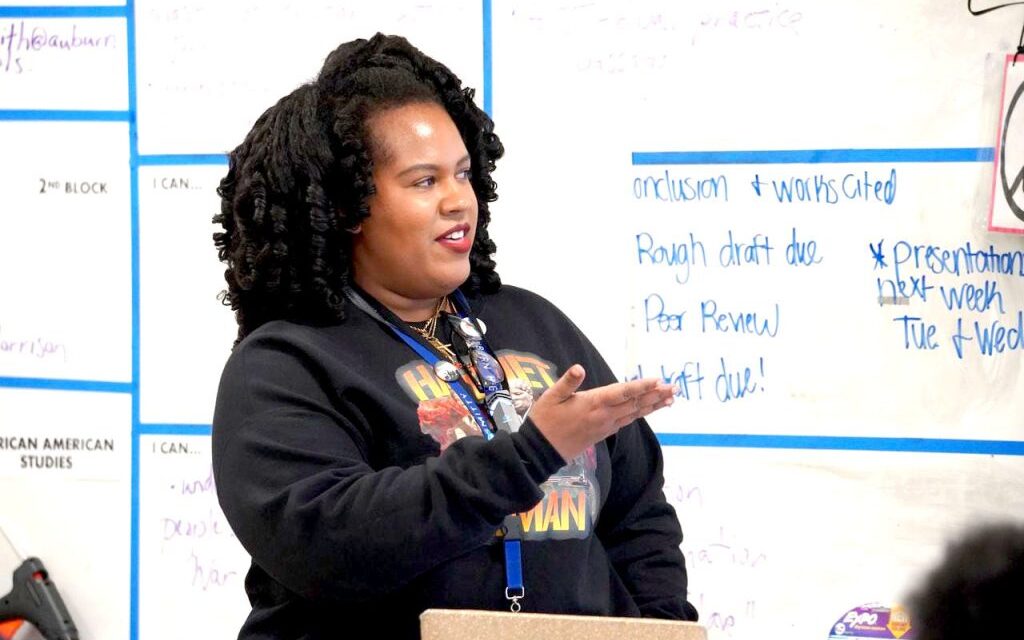

Smith, who has been teaching for almost a decade, recently took over Auburn High School’s popular African American studies course. The semester-long elective is one of just a handful of African American studies courses across the state, and students requested to bring it back this year after its original instructor switched jobs.

The survey course is designed to introduce students to a range of African American history, she said, and give them space to ask questions that may not be covered in general history or English classes. From the beginning, Smith makes sure her students are able to get a strong foundation in African history.

“It’s always been a part of my curriculum,” she said. “Some of that’s natural. I am Black, I am an African American, so in everything I teach, I’ve always really made sure to not just cover the experiences of my community and my culture but Black and Brown people as a whole.”

Following the format of “Roots,” the class traces a family’s lives in Africa, then the Middle Passage, and later in the Great Migration, drawing connections across time and space.

Every test she gives quizzes students about one of those families. In one lesson, the class creates their own coded message, following the format of Negro spirituals that were passed down family lines.

By the end of the course, the class has three or four generations worth of Black history to look back on.

“I just kind of modeled it after the way that I think,” she said. “Because so much of my life has been modeled after connections to my family members and to my ancestors, and because I was brought up knowing that, and a lot of students aren’t, I just thought, well, if they can’t relate back to theirs, they can relate back to this mythical family.”

Lessons learned

Sometimes, Smith takes time to share pieces of her own family’s history with the class, such as an 1892 slave narrative that had been passed down for generations. But largely, she wants her students to draw their own meanings and connections from the course.

Oftentimes, that means she has to meet them where they are, by mixing classroom discussions with hands-on activities and other engaging learning experiences.

She also learned that she can’t estimate how much students might know about African American history.

Smith was shocked to find out that several of her students hadn’t heard of the Montgomery Bus Boycotts. So the next day she changed her whole classroom around to look like a bus, and guided her students through a simulation to drive home the significance of the events.

And importantly, she said, students can make surprising connections if educators make an effort to bring in current events and trends. Her class often connects historical tropes to more modern examples, like “digital Blackface,” she said.

“History really is a relevant thing,” she said. “It’s still happening. It’s not something that’s in the past. It’s just past events that give more context to what’s happening now.”

Finding other voices

It can take a lot of work to develop a course like this, she said, but not because the information isn’t there. Sometimes it’s just not prominent.

Figures like Thomas Edison and Alexander Graham Bell are talked about more often than people like Lewis Latimer, a Black man who invented and patented a process for making the carbon filaments that make the light bulb possible.

“In the same way that history builds and moves along based on things in our past, the same is true for any major innovation or invention that we have,” she said. “There are other voices that are a part of it.”