By Javacia Harris Bowser

For The Birmingham Times

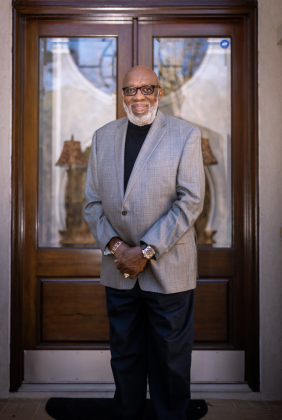

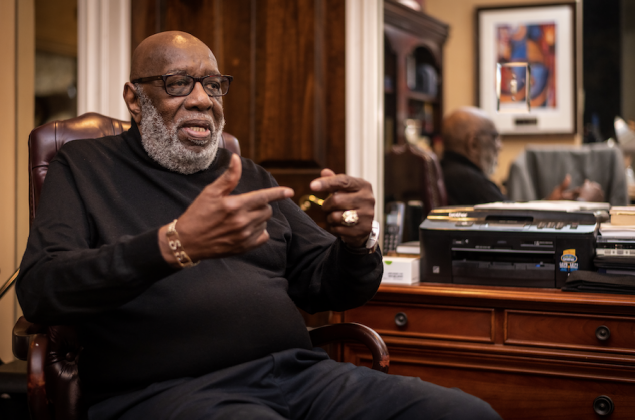

It’s an unseasonably warm January morning, and Dr. Shelley Stewart is sitting in his home office in Shelby County, Alabama. At first glance, the space looks like an ordinary room with books on shelves, papers on a desk, and a file cabinet against a wall. But this room holds a wealth of mementos that demonstrate why Stewart is an icon in Birmingham and beyond.

To many, Stewart is a Civil Rights Foot Soldier and radio great. But Stewart, who spent his childhood living in basements and barns, doesn’t see himself that way.

“I’m that same little homeless street kid even to this day—no more, no less,” said Stewart, 88.

When Stewart was 5 years old, he witnessed his father murder his mother with an ax. Homeless by age 6, he sought shelter in a horse barn and later in the basement of the home of a white family that lived off Highway 78 East between Irondale and Leeds.

“Although I’m a man of this age, I still feel that I’m that homeless kid crying for more—crying for more love, trying to give love, trying to get respect, trying to give respect,” Stewart said. “I still feel like I’m that kid who wants to do more, to make things better, to improve my life.”

The Road South

Despite the unimaginable trauma Stewart endured growing up, he found a way to thrive.

Mamie L. Foster, his first-grade teacher at the Rosedale School in Homewood, Alabama, told him that if he learned to read and got a good education, he’d be able to do and be anything. Through Foster’s encouragement and with the books he found in the home of the white family he lived with briefly, Stewart became a voracious reader. He particularly liked books about history, and he read the New Testament of the King James Version of the Bible three times.

Despite being bullied because of his dark skin, Stewart joined the drama club at school. During his time at A.H. Parker High School, Stewart worked multiple jobs—bagging groceries, selling newspapers, and operating the elevator at a local department store.

Still, he found time to write for the school newspaper, and when a local radio station wanted a student to give a weekly report of high school happenings, Stewart was tapped for the job. This laid the foundation for a broadcasting career that would span more than five decades and lead to world renown and a place in Black history.

On one of the bookshelves in Stewart’s home office stand two books about his life—“The Road South” and “Mattie C’s Boy: The Shelley Stewart Story”—through which he has shared his story and his wisdom.

Also in his office are the numerous awards Stewart has garnered across decades. He’s received the American Advertising Federation’s Silver Medal Award. He’s been inducted into the Birmingham Business Hall of Fame and the Alabama Broadcasting Hall of Fame. The Southern Poverty Law Center gave him a Lifetime Achievement Award. And in the early 1990s, he received the Drum Major of Justice Award from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) along with other activist artists like Maya Angelou.

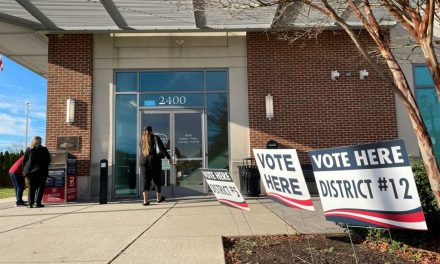

Of all these accolades, however, Stewart said the one that has meant the most was the recent Putting People First Award he received from the Birmingham Mayor’s Office in October 2022. The city of Birmingham honored Stewart during its annual AWAKEN event, which is held during the week of the Magic City Classic and celebrates the legacy of community leaders and activists who have shaped the city.

More Than a Record Spinner

While growing up in Birmingham’s Rosedale, Collegeville, and Irondale neighborhoods, Stewart’s dream wasn’t to go into radio.

“I really wanted to be an attorney [because] I had read so much about the fights and struggles for equality,” said Stewart, who believed being a lawyer would allow him to do something about the oppression he had read about and experienced firsthand.

Eventually, he would see that radio could also be used as an effective tool to fight for justice.

“He became more than a record spinner,” Stewart said of his “Shelley The Playboy” persona.

“The Shelley that was existing then and now was not about showing off,” he said—it was always about fighting for equality.

Stewart’s first professional radio gig was at WEDR-AM in 1949, where he earned $17.50 per week. That same year, he also worked at WBCO-AM, a station that started broadcasting from Bessemer, Alabama, in 1953 and changed its call letters to WYAM-AM in 1960.

Stewart briefly served in the U.S. Air Force, and he took classes at the Cambridge School of Broadcasting, which operated in New York City from 1949 to 1956.

In the 1950s, Stewart became a wildly popular radio personality across the South. Though based in Birmingham, Shelley The Playboy was on the air in other cities, including Jackson, Mississippi, and Shreveport, Louisiana.

Stewart was also a stand-up comic and emcee. Unknown to his audiences, Stewart would often draw on dark life experiences for his comic routines.

“I’d say, ‘Let me tell you, rats taste like chicken,’” Stewart said. “But they didn’t know my father was killing rats and feeding them to my brothers and me.”

In the 1960s, Stewart worked for WENN-AM in Birmingham, and his popularity crossed color lines—even in the segregated South. On July 14, 1960, Stewart deejayed a dance party for about 800 white teenagers at Don’s Teen Town, which was located just outside of Bessemer. That night, a group of 80 members of the Ku Klux Klan surrounded the building and demanded that the manager, Ray Mahoney, send Stewart out. Instead, Mahoney announced the siege to the crowd, and the teens bum-rushed the Klansmen, allowing Stewart to escape.

Also in the 1960s, Stewart and other disc jockeys helped the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and other leaders organize the historic 1963 Children’s March in Birmingham, which led to negotiations that would eventually dismantle the state and local laws enforcing racial segregation that were in place across the Southern U.S., commonly called Jim Crow laws, in what was then the nation’s most segregated city.

Mass Communicator

Stewart used his radio show to disseminate key information about planned demonstrations, and he’d use his broadcast to speak to youth protesters in code as a means of misdirecting police. For instance, on May 2, 1963, Black kids all over Birmingham heard Stewart announce, “Kids, there’s going to be a party at the park. Bring your toothbrushes because lunch will be served.” According to Diane McWhorter’s Pulitzer Prize-winning “Carry Me Home: Birmingham Alabama and the Climatic Battle of the Civil Rights Movement,” “This was a coded call for a mass demonstration; you need your toothbrush when you go to jail.” More than 800 hundred kids, some as young as 6, skipped school on that day—one of the most pivotal during the Movement, when 1,000 were arrested.

“I’m one of the people who was called not as an ‘activist,’ as they call it, but as a person who could slip in and strategically talk about things, about how they can get things done,” Stewart said. “So, I was involved in most of the meetings, but I went in as a mass communicator, not a class communicator.”

In other words, Stewart was a deejay for the people. Throughout his career, Stewart has been community focused. He knew his listeners. He’d go to their houses for a weekend fish fry or just to sit on the front porch to chat. When he saw young people on the street up to no good, he’d pick them up and take them home.

As a radio personality, Stewart felt his duty was to use entertainment to deliver important messages to the masses and to be connected to the community he served. Even though today’s media landscape is vastly different from that of Stewart’s heyday, he’s certain this method still works—and viral social media posts aren’t enough.

“You’ve got to feel it,” he said. “It’s got to have some soul to it.”

Brian Ward, a Black radio scholar and the author of “Radio and the Struggle for Civil Rights in the South,” has said that Black radio of the 1960s “helped fashion the new Black consciousness, the sense of common identity, pride, and purpose upon which Civil Rights activism was predicated.”

Stewart laments the dwindling number of Black-owned radio stations and Black locally-based radio personalities. He’s confident they could have a real impact on their communities, just as he and his peers did decades ago.

The Parable Guru

Anyone who knows Stewart knows that one of his favorite ways to pass on his wisdom is through aphorisms.

Life is hard by the yard, but it’s a cinch by the inch.

Despite all the trials and tribulations, he’s faced in life, Stewart has found triumph one step at a time.

Be careful of the words that you say. Always keep them soft and sweet because you never know from day to day which one of those same words you may have to eat.

Stewart endured abuse and discrimination throughout most of his early life, but still chooses to be kind with his actions and words.

Anger is only one letter away from danger.

Stewart believes that division—among communities and even within families—is the root of so many societal issues.

His daughter, Sherri, calls her father a “parable guru,” recalling his memorable proverbs.

How can you beg for rain and curse the mud?

“That’s how he teaches,” she said.

Family

Shelley Stewart has five children, five grandchildren, and five great grandchildren. He and his wife, Doris, have been married for 50 years.

Honoring family is important to him, and in 2007 Shelley Stewart founded the Mattie C. Stewart Foundation.

“That’s his passion,” Sherri Stewart said of the foundation, which is named for Stewart’s mother.

The goal of the foundation is to reduce the dropout rate and increase the graduation rate of high school students. Sherri Stewart says her father believes that illiteracy and a lack of education are at the root of many of the ills that plague communities, such as poverty and crime.

As he sits in his home reflecting on the future, Stewart has a simple but profound wish: “I don’t want to become a buried treasure,” he said. “In other words, I don’t want to carry the knowledge on to the beyond. I’m willing to share.”

As he shares his stories, Stewart pulls out papers and photographs stashed in a file cabinet drawer. He has snapshots with famous entertainers like Gladys Knight, Lou Rawls, and Vanessa Williams; with history makers like Rosa Parks; and with leaders like former President Jimmy Carter the late U.S. Rep. John Lewis. He reveals mementos from the time he spent handling public relations for legendary singer-songwriter Otis Redding, and he shares stories of his friendship with Sam Cooke, one of the most influential soul artists of all time.

Despite his many accomplishments, Stewart doesn’t find his value or self-worth in awards.

“I haven’t asked for anything but respect, and I hope this will be a better place when I’m gone,” he said.

Atop one of the tables in Stewart’s home office rests a microphone that some might think is there as décor, as a reminder of Stewart’s incomparable broadcasting career. But the microphone will soon be put to use. To keep sharing his words of wisdom, Stewart plans to be a part of a podcast that he’s confident will have a worldwide audience.

“I’ve been running, but I ain’t tired yet,” he said. “I’m not giving up, and I haven’t given out.”