Time travel in Alabama can be a dangerous thing, and we just got off on the wrong stop.

This is Dexter Avenue, all right. The Alabama capitol is here but no monuments yet. The trees are sparse and behind us is a new building still called by its original name, the Second Colored Baptist Church.

A little farther down Goat Hill, there are thousands of angry men and they’re heading our way.

Waiting for them at the capitol steps are the Montgomery city police and Alabama militia. The governor has ordered them to carry 40 rounds of ammunition each, or so the papers say, and word is light artillery is being brought in as we speak.

This probably isn’t the march on Montgomery you’ve seen in your textbooks.

This is Inauguration Day 1894.

And we’d better hide.

The protestors are angry and they’ve come with no promise of being peaceful. Pitchforks and torches are hardly a metaphor, and they’ve probably got some guns, too. They seem ready to turn the town over, and leading their charge is a white man who looks like a walrus that’s taken human form.

Reuben Kolb is here to take the oath of office as Alabama’s 29th governor, only the election officials say he didn’t win. Kolb has called his supporters to Montgomery to set them straight and take office anyway.

If this seems a little January 6-ish to you, there are important differences.

First, the election really was rigged and Kolb was cheated (and not for the first time, either).

And second, if you look into that crowd, you’ll see some Black folks, too.

Yes, this is a biracial political coalition in 19th-century Alabama.

Weird, huh?

What we’re witnessing is the closest Alabama ever came to a Blazing Saddles-type ending — where poor whites and freed Blacks realized they had more in common with each other than with the land barons who ran this state.

Tomorrow this will be front-page news across the country, though few will remember it a century hence.

Kolb is an unlikely leader for this insurgency. He was born in affluent, influential Barbour County — the so-called “Home of Governors” — where 20 years back a white militia ambushed and murdered Black voters on their way to the polls. Kolb’s mother was a member of the powerful Shorter family. During the Civil War, he fought as a captain in the Confederate army, and he returned to Alabama to be a planter, like many other white elites.

But he was also kind of a nerd.

Rather than growing cotton, he experimented with crop rotation and nearly went broke before he developed a new strain of watermelon called Kolb’s Gem. Like a Honeycrisp apple of the 19th century, the sweet, hardy fruit was a hit, and soon he was selling its seeds all over the country. At home in Alabama, he preached the gospel of agricultural science and helped found the Alabama Department of Agriculture. In his evangelism, he won the trust of poor white dirt farmers and Black sharecroppers. When he ran for governor, he had the radical idea of making them his political base — Kolbites, as they came to be known.

But if this seems a bit like a White Savior story, you’re absolutely right.

When Kolb and his citizen army get to the top of that hill, he’s going to chicken out. The governor will threaten him with arrest, and before the Kolbites start punching out windows or fighting with cops, he’ll relent and tell his folks to be peaceful. He’ll give a little speech from the back of a wagon, his dispirited supporters will meander home, and the folks who really run Alabama will hold the real inauguration.

But what happened this day terrified Alabama’s ruling class, and in a few years, they’re going to make sure nothing like this ever happens again. Mostly south Alabama planters and north Alabama industrialists, they’re a nasty bunch who stole what they didn’t inherit — money, land and power— and they’ll salt the earth before they share it. Soon, they’ll leverage every institution they control to divide this state, and they’ll pass a new state constitution to keep it that way, maybe forever.

But we’ll catch up with them later.

Let’s get out of here. I want to show you where this is going.

Alabama politics in black and white

It’s 2021 and at least we landed somewhere safe, as long as we don’t catch COVID. The Alabama Statehouse has the ventilation system of a Civil War submarine, and this is one of its smaller committee rooms — ideal for keeping spectators to a minimum.

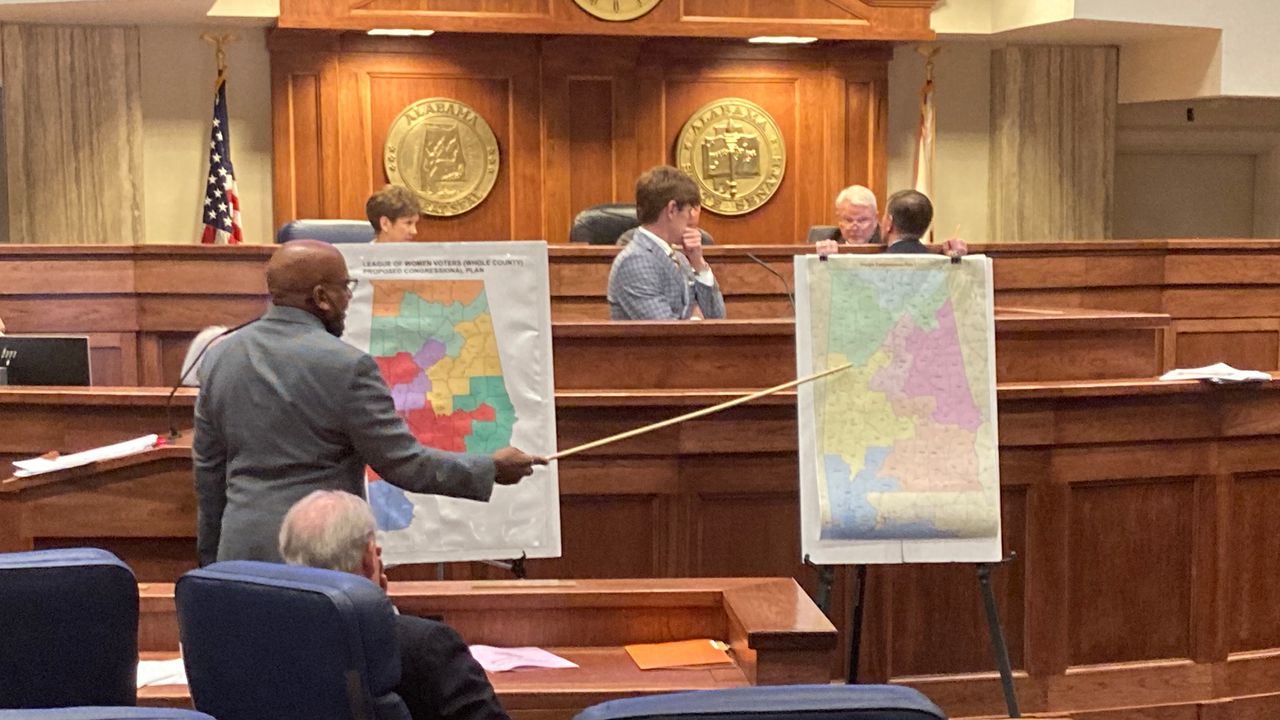

It takes four days, minimum, to pass a bill through the Alabama Legislature. Redistricting is on a legislative fast track and this little committee room is where it leaves the station.

The committee is a peculiar one — made up of Alabama House and Senate members. The lawmakers sit around tables arranged in a horseshoe — with white Republicans on one side and Black Democrats on the other.

At the head table are the two co-chairs, both Republicans.

One is state Rep. Chris Pringle from Mobile. If he looks at me funny, it’s because, a few months back, he filed a bill to ban Critical Race Theory from Alabama schools. I asked him to explain what CRT was, and he sputtered some weirdness about white executives being forced ito re-education camps.

The other co-chair is state Sen. Jim McClendon of Springville. He’s a retired optometrist and a member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Occasionally, he directs state funding to a little museum his SCV camp runs. That museum has a Confederate battle flag out front. When I ask him about it later, he’ll wonder aloud why anyone would ever be offended by that flag.

But today, these lawmakers are here for a different job — redrawing Alabama’s district lines, including those for Congress.

Typically, redistricting is a two-year process, but because the U.S. Census Bureau delivered results late this time, it’s being radically accelerated. The only people to have seen the new maps are a few House and Senate Republicans, and now they expect everyone to vote on it, no questions asked.

State Rep. Chris England, D-Tuscaloosa, isn’t having it.

“I did not see these maps until yesterday,” England says. “We’re undertaking a pretty massive task, with the amount of information presented to us, to come here and say, I need you to vote today.”

England rattles off a list of questions. He wants to know what criteria they used. He wants to know whether anyone did a racial polarization study. One question is so simple, that the fact it’s a question at all reveals a lot about how this process works — he wants to know who drew the maps.

When England is done talking, Pringle quickly recognizes another lawmaker, state Sen. Bobby Singleton, D-Greensboro.

“Are you going to answer his questions?” Singleton asks.

“We’re going to get back with him,” Pringle says.

This riles the Democrats in the room and it’s this moment right here I want you to see. In the Alabama Legislature, we’re not looking at a simple partisan split, but a racial one, too. All but one member of the Republican caucus is white. All but two members of the Democratic caucus are Black.

Partisanship layers over race so neatly, white lawmakers can run over Black lawmakers, disregard their concerns and occasionally treat them with naked contempt — and, when they’re done, say it’s because they’re Democrats.

Partisanship is the means by which white people in Alabama subordinate Black people and then tell themselves it has nothing to do with race.

But this time the pushback from Black lawmakers forces Pringle to answer some of England’s questions.

“You stated that it complies with the Voting Rights Act,” England tells Pringle. “You also say that it complies with the 14th Amendment equal protection. So I’m asking you, how?”

Again, Pringle gets testy.

“I see where you’re going, and let’s do this: You tell me where it doesn’t,” Pringle says. “How’s that?”

But England doesn’t relent, and a few questions later, Pringle reveals something interesting.

A racial polarization analysis was done for all the congressional districts but one, he says — the 7th Congressional District, the only majority Black district in Alabama. Also, when the committee’s demographer drew the map, he had turned off race as a criterion, he says.

The Black lawmakers are frustrated because they suspect their white colleagues of packing as many Black voters into one district as they can get away with. Called stacking and packing, this makes races in all the adjacent districts easier for them to win.

When it’s Singleton’s turn to speak again, he tells the committee he’ll be bringing another Congressional map, one which gives Black voters a say in state races proportionate to their part of Alabama’s population — just like they have in the state Legislature, and just like they have on the state school board.

It’s a plan the Legislature will ignore.

It’s been 127 years since Reuben Kolb’s populist charge up Goat Hill, and Alabama politics is still racially segregated.

We’ll catch up with the Power Express later, when it jumps the legal tracks and crashes into the United States Supreme Court.

Now, it’s time for us to return to the scene of the crime.

Brace yourself. We have to go back to 1901.

The Magnificent System

It’s 1901 at the Alabama capitol, one of those spring days in May when the weather can’t decide what to be. The capitol staff keep futzing with a new contraption here, electrical fans, which they turn off and on as the delegates complain that it’s too hot and then too cold.

The first order of business is who will sit where. The Democrats say they’re entitled to first pick, since they’re in the majority, but after some fussing from the Republicans and Populists, they agree to draw numbers out of a hat. Not everybody is satisfied.

“We might as well shoot craps or draw high spades,” a delegate from Walker county yells at the chair.

There’s also a spell where a few delegates question the expense for stenographers. Everything here will be written down. A few seem to think that’s not a great idea — a written record today could be evidence in court later.

And then they set to business.

These 155 delegates have come together under a common cause. They’re here for election security.

This is the 1901 Alabama Constitutional Convention, but the rhetoric might sound familiar to 21st century ears.

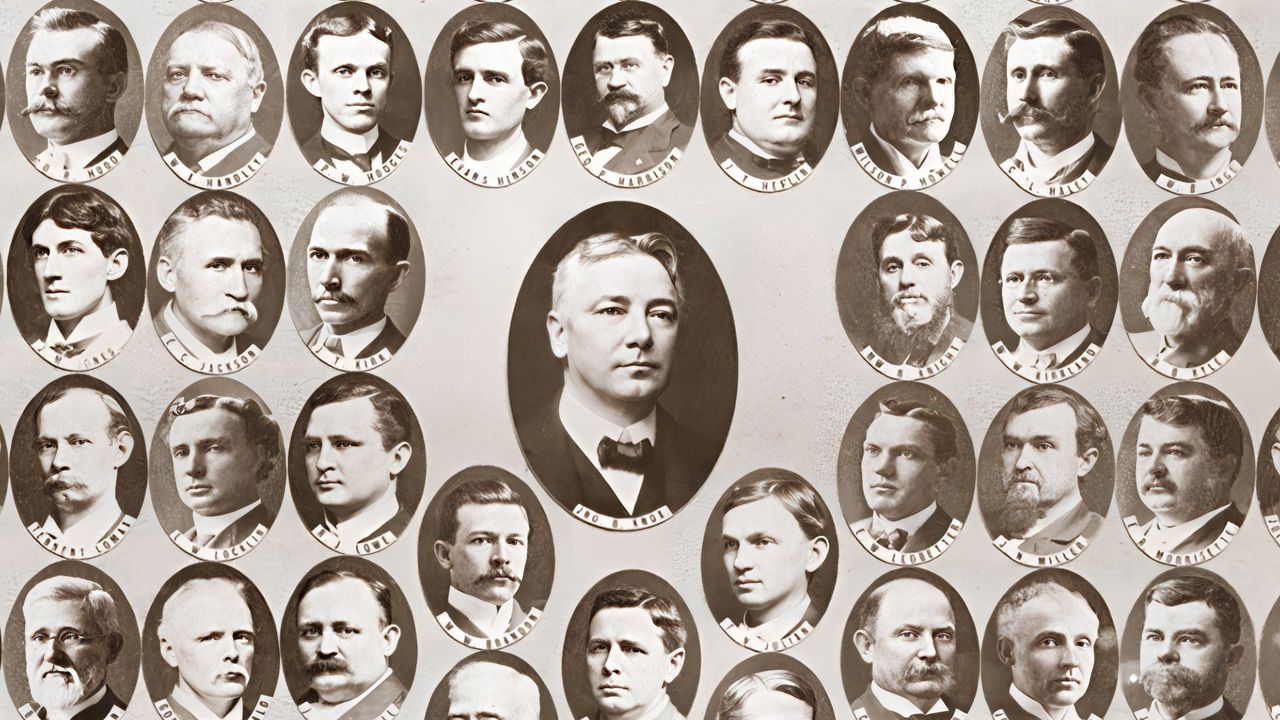

“There is no higher duty resting upon us, as citizens and as delegates, than that which requires us to embody in the fundamental law such provisions as will enable us to protect the sanctity of the ballot,” John Knox, a lawyer from Anniston, says after being chosen the body’s chairman.

For decades cheating at the ballot box had undermined the legitimacy of state government and tempted the familiar specter looming over Alabama politics — federal intervention.

Reuben Kolb wasn’t wrong when he said he’d won the governor’s race. His victory really was stolen.

And these are the men who took it from him.

The election fraud they claim they want to stop is their own.

In 1874, violent voter suppression and blatant election rigging unseated the Reconstruction Republicans and returned white Democrats to office in Alabama and throughout much of the South. With this reclaimed power, the South brokered an end to the federal oversight of Reconstruction in 1877.

At first, Black voting fell sharply, especially in the Black Belt, the fertile region where plantations had flourished and Black people outnumbered whites, in some places three-to-one.

In an 1874 city election, about 1,200 Black voters cast ballots in Eufaula, Ala.

In the 1876 presidential election, that number fell to 10.

But then something curious began to happen. Black people in the Black Belt started to vote again — at least on paper — but not for the party of Lincoln. This time they cast their ballots for the white Democrats favored by their former enslavers.

This wasn’t some early struggle for voting rights. Rather, Black Belt planters built an elaborate scheme that gave them control of Alabama.

They called it “the magnificent system.” This fraud is no secret. In fact, several delegates at the 1901 convention speak of it proudly — in the open and on the record. On the old House floor, a Perry County delegate, Charles Greer brags about it with the over-the-top flourish of a carnival barker.

“It is an art, gentlemen, learned only by experience, one fraught with danger—a ‘magnificent system’ that cannot be inherited or perpetuated,” Greer says. “It is an achievement of faith with the evidence not seen. It is Christianity, but not orthodox. It is prime but humane. It is wrong but right.”

In reality, the “magnificent system” is not so mystical. In the Black Belt, they stuff ballot boxes where they can, move voting precincts without warning, and bribe anyone otherwise reluctant to help cheat. Planters threaten the livelihoods of the Black sharecroppers and force them to vote how they want. And if that doesn’t work, they threaten their lives.

Mess with the magnificent system, and you’ll get lynched.

And they’ve used this system to beat the folks they don’t like — freed Black men and poor white folks elsewhere in the state, including “radical” Republicans and those Populist Kolbites.

When Reuben Kolb ran for office, it was the magnificent system that delivered the votes for his opponent.

But most folks at this convention understand this reign of terror can’t last. Urban elites and big city newspapers are fed up with the Black Belt’s corruption. And there are already Yankee congressmen threatening a second Reconstruction.

In the Black Belt, younger Black voters are ready to foment an uprising, warns Greer, the Perry County delegate. Just before the convention, a sheriff had told him they were organizing.

“It was purely out of fear they did not attempt to put their plans into execution,” Greer says. “Nightly meetings were held and this Convention discussed, and while none became sufficiently emboldened to tell their secrets, it was plainly seen that under a proper leadership they would have entered the contest even at the risk of certain bloodshed.”

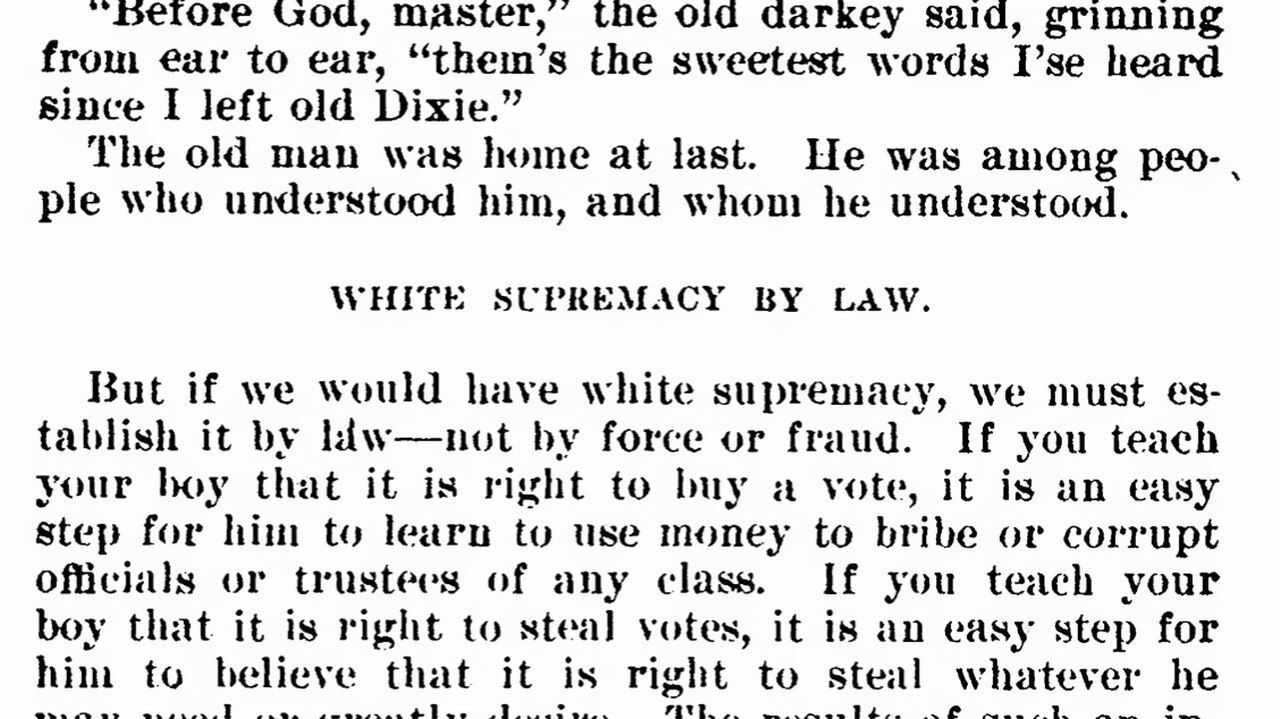

No matter how cavalier this all sounds, delegates believe this “magnificent system” to be a moral depravity — a necessary evil — but one that might leach into other aspects of the social order.

“The results of such an influence will enter every branch of society,” Knox warns the delegates. “It will reach your bank cashiers, and affect positions of trust in every department. It will ultimately enter your courts, and affect the administration of justice.”

It might even risk their eternal souls. Stealing is still a sin, after all.

That’s what the convention chairman Knox means when he says, “But if we would have white supremacy, we must establish it by law. Not by force or fraud.”

Whites won’t have to steal Black votes if Black people no longer have a vote. These men are here to disfranchise every Black voter.

But they’ll have to get around the U.S. Constitution and its post-Civil War amendments.

Lucky for them, they have model legislation to follow, invented in Mississippi and already blessed by an unlikely ally — the United States Supreme Court.

Defusing the bomb

It’s 2021 again and this time we’re in a slightly bigger committee room at the Alabama Statehouse. This room has more space for onlookers than the last, and its proceedings are streaming online.

A joint committee of House and Senate members, in addition to some outside lawyers and consultants, are trying to clean up the Alabama Constitution of 1901.

Over the next year, they will carefully strip out racist language, clean out portions overturned by the courts and reorganize the nearly 1,000 amendments. When their work goes before voters next year, they’ll call it the Alabama Constitution of 2022.

But it will really be the same old wretched document with the epithets erased.

But here’s the thing I want you to see a year before the vote.

One of the committee members, Birmingham lawyer Stan Gregory, is questioning whether poll taxes are inherently racist, and there’s some confusion among the committee members about whether other states still use poll taxes.

If you look closely at Rep. Merika Coleman, D-Birmingham, you might see her grinding her teeth, but she’s keeping it together nicely.

Before the meeting caterwauls out of control, the head of the Legislative Reference Service, Othni Lathram, offers to do some research and report back to the committee. Lathram is an expert at defusing political bombs and he’s gently slow-walking this one to a dumpster out back.

Even 120 years since the convention in Montgomery, there are folks who will question whether a poll tax in the 1901 Constitution is truly racist.

Such is the power of race-neutral racism — working exactly as it was designed.

Break’s over. Now, back to 1901.

Inventing race-neutral racism

It’s 1901 again, and the convention is nearing its end. Many of the delegates have late-summer vacation plans, and Thomas Bulger, a delegate from Tallapoosa County, is getting frustrated.

The convention leaders keep pushing hare-brained ways to take the vote away from Black people, but each scheme they come up with would catch some white people in its net. Bulger doesn’t understand why it has to be so complicated, and he’s not alone. If left to him, he’d write “negroes can’t vote” on a slip of paper and go home.

“What we would like to do in this country, more than any other two things, would be to disenfranchise the darkeys and to educate the white children,” he says, using the second-worst slur in the convention minutes. “If we can do that, just let us alone and we will continue to have the greatest State in the American Union.”

The lawyers among the delegation — and they are many — try gently to explain to their cohorts that such a state system won’t work under the U.S. Constitution.

It’s a message Knox, the chairman, has been preaching since the very first day in his opening speech: “And what is it that we do want to do? Why, it is, within the limits imposed by the Federal Constitution, to establish white supremacy in this state.”

Luckily for them, in 1901, they now have the U.S. Supreme Court on their side. In recent years, the court has been on a tear, weakening the Constitution’s promise of equal protection.

In 1896, the court ruled that Louisiana train cars could be segregated by race, as long as the accommodations were somewhat similar. Plessy v. Ferguson will be a handy hammer of Alabama politics for decades to come.

But even more useful for these delegates is a recent decision, Williams v. Mississippi. In 1898, the court ruled Mississippi’s 1890 Constitution did not violate the 14th Amendment.

With that decision, the court gave Alabama not just a tool for disenfranchisement, but the whole toolbox — literacy tests, residency requirements, requisite property ownership … and poll taxes.

“The constitution of Mississippi and its statutes do not on their face discriminate between the races, and it has not been shown that their actual administration was evil; only that evil was possible under them,” the nation’s top court said.

And they weren’t wrong about that last part. There’s going to be some evil to come, all right.

But what this means now, to the Alabamians assembled in 1901, is that to withstand court challenges, racist laws with racist effects will have to be wrapped in the guise of race neutrality.

Louisiana, South Carolina and North Carolina have already followed Mississippi’s lead. Now it is Alabama’s turn.

Alabama’s suffrage committee copied and refined the Mississippi plan, and the convention delegates are in agreement about the goal of taking the vote from Black people.

Where they are split is on how many collateral white people are acceptable. Every Mississippi mechanism hurt some white voters, too — the poor and the uneducated. Many here are fine with that.

Emmet O’Neal, a future Alabama governor and member of the convention’s suffrage committee, proposes a solution.

“It was the illiterate and uneducated white man that fought the battle of the Confederacy,” he says. “They and their descendants were educated not in books but in the traditions and principles of free government.”

The new constitution will exempt Confederate soldiers and their descendants from some of the voting restrictions.

“The negro on the other hand has no traditions of liberty, no pride of ancestry, no environments which fit him to intelligently discharge the great duties of citizenship,” O’Neal says, despite Black Alabamians having done those things during Reconstruction.

Soon the Alabama Constitution of 1901 will be ready to go before voters.

The convention’s explicit racism of disfranchisement is easy to see. In 2011, U.S. District Judge Lynwood Smith will say in a court order just how hard it is to miss.

“Indeed, one could not throw a dart blindfolded at the pages upon which the suffrage debates are recorded without hitting some racially offensive comment by a delegate to the Convention,” Smith wrote in a case challenging disparities in education funding.

The disenfranchisement is only one poison the delegates injected into Alabama’s bloodstream, and there’s so much more than just that toxin in its many pages. The lasting effects of the convention’s bigotry have survived through what Alabama historian Wayne Flynt called “the less obvious and deeply embedded provisions.”

Come with me and I’ll show you one of those lasting provisions in action.

The sneaky stuff lasts the longest

It’s 2021 again. We’re back at the Legislative reapportionment committee, which just rammed through Alabama’s Congressional districts with a racial-split vote, and now it has turned its attention to the state House and Senate maps.

They’re going to ram this one through, too, but not before state Sen. Roger Smitherman, D-Birmingham, says his piece.

The state districts poking into Alabama’s largest county is an even uglier problem than the congressional map, he says.

In the Alabama Legislature, the larger counties have what are called local delegations. These smaller groups control local bills. To sit on these committees, lawmakers don’t have to live in the counties, they only need to have a piece of the county in their district.

Jefferson County is a majority-Democrat county and home of Alabama’s largest majority-Black city, Birmingham. But the districts have been drawn to give lawmakers outside the county a piece here and a piece there so white Republicans will still control the delegation.

One state House member, Rep. Kyle South, R-Fayette, lives closer to Columbus, Miss. than Birmingham, and yet he serves on the committee.

“There is no reason on earth that Jefferson County should be split among seven senators,” Smitherman says.

But there is a reason, it’s just not one Smitherman likes, and if you look at what the Legislature has done, you can see why.

When Birmingham attempted to set its own minimum wage, lawmakers who don’t live there made it illegal for the city to do so.

When majority-Black cities tried to move their Confederate monuments, it was the Legislature that made them keep them in place.

When county sheriffs and city police pleaded with lawmakers to leave pistol permits alone so they could get illegal, unregistered guns off city streets, the Legislature ignored them and made it legal for anyone to carry a pistol without a license.

Ironically, the 1901 Convention concentrated power in Montgomery to keep local control — called “home rule” — away from poor, uneducated white people in rural areas, but as the federal courts and the Voting Rights Act disarmed their racist disfranchisement, this tool has worked to control majority-Black cities and counties.

And perhaps the most lasting effect of the 1901 convention has been Alabama’s tax structure, which caps property taxes and limits property tax to its “current use,” not what the property could be sold for.

The net effect has been that urban school systems and affluent suburbs have sufficient funding for education, while rural schools struggle to meet basic needs.

In 2011, a lawsuit in federal court challenged the state’s system for funding public schools. Judge Lynwood Smith ruled in favor of the state, saying the plaintiffs had not proven that school funding was racially discriminatory, only that it disfavored rural systems, white and Black.

But in the massive 854-page ruling, he blistered the Alabama Constitution of 1901.

“With regard to the first of those elements, the overwhelming weight of evidence in this record establishes — clearly, convincingly, and beyond reasonable debate — that virtually every provision of the basic charter of Alabama government drafted by the delegates to the 1901 Constitutional Convention was perverted by a virulent, racially-discriminatory intent,” he said.

And Smith honed in on something the plaintiffs didn’t address in their lawsuit — the Constitution of 1901 had been passed by fraud.

The Magnificent System strikes again

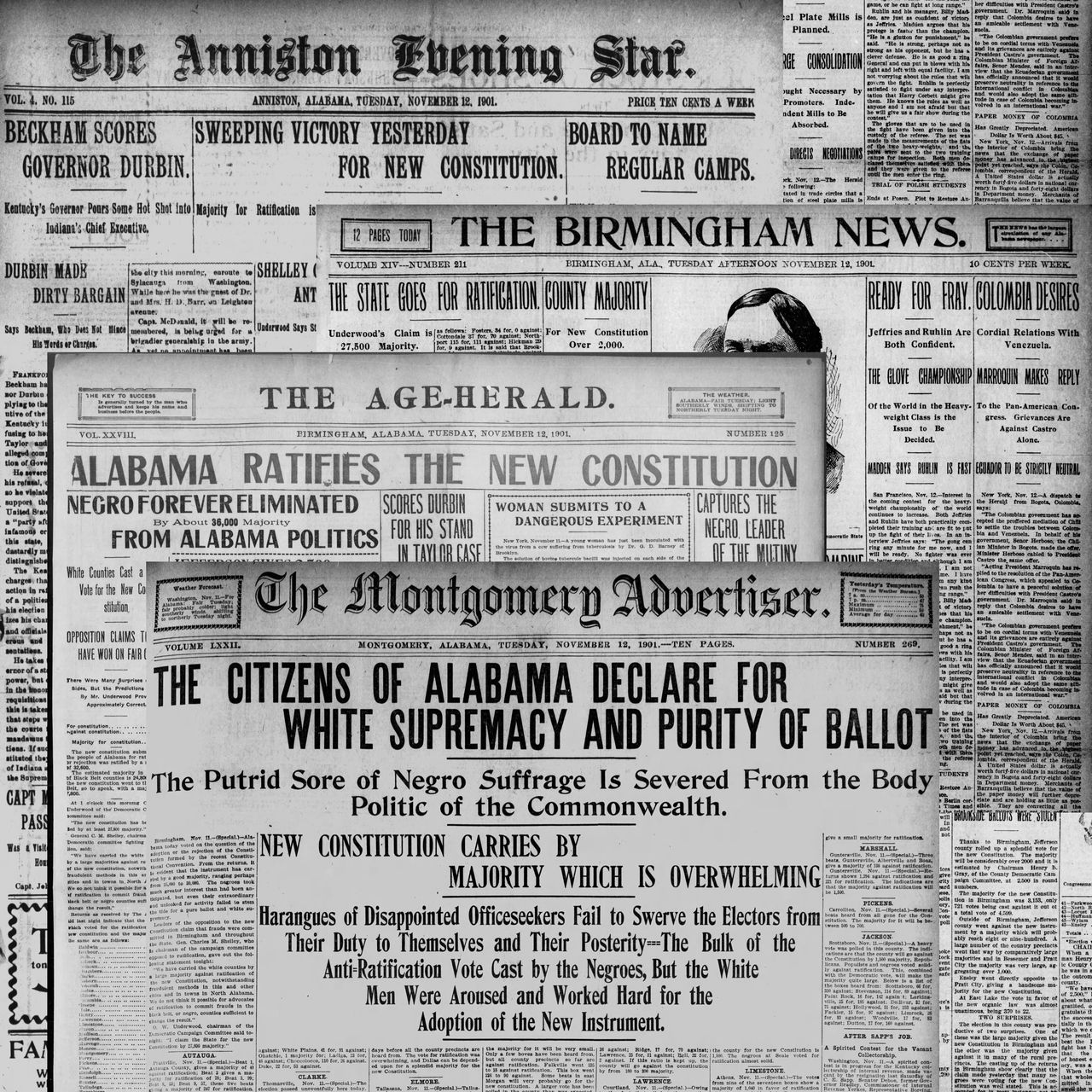

It’s Nov. 12, 1901, and we missed the big event. Yesterday, Alabamians went to the polls, and by the stack of newspapers in front of us, you might think they voted overwhelmingly in favor of the new constitution.

“State goes for ratification,” the lead headline in The Birmingham News says.

Compared to some of its competitors, the News is being subdued.

“Negro forever eliminated from Alabama politics,” the Birmingham Age-Herald tells us.

Another goes all out with typefaces typical of unexpected wars or the violent deaths of presidents.

“THE CITIZENS OF ALABAMA DECLARE FOR WHITE SUPREMACY AND PURITY OF THE BALLOT,” the Montgomery Advertiser says. “The Putrid Sore of Negro Sufferage is Severed from the Body Politic of the Commonwealth.”

The vote was decisive, the papers say — which is, to use the 21st-century term, fake news.

They’ll be counting votes for the rest of the week, and it’s a close one.

Ahead of the vote, the Alabama Democratic Party’s campaign committee adopted a succinct slogan in support of the proposed constitution: “White supremacy, suffrage reform, and purity of elections.”

The strategy was simple — divide voters by race and they’d win.

Only many white voters in Alabama didn’t buy it. Dissenters had two objections.

First, many poor whites suspected they would be disfranchised, too. On this, they were correct. The “grandfather clause” set a clock on their disfranchisement, delaying it a couple of generations. Within a few decades, the 1901 Constitution will deny the vote to more white residents, by raw numbers, than Black residents.

Second, while the new constitution will deny Black people the vote, it still counts them when splitting up seats in the Legislature. As a result, the white planters in the Black Belt will have even more power under the new system than under the violent old one.

When more careful and discerning tallies are taken later, important facts will stand out.

Among predominantly white Alabama counties, ratification failed.

Again, it was the Black Belt that delivered the victory.

To accept that this was a legitimate referendum, you have to believe that Black voters throughout the region voted overwhelmingly to deny themselves the right to vote.

In Lowndes County — a Black Belt county that will give birth to the Black Panther Party decades from now — Black voters outnumbered white voters, five-to-one, and yet the county voted 94% in favor of ratification.

The Alabama Constitution of 1901 was supposed to put an end to voter fraud, but the whole process has been a fraud. The ratification vote was a fraud, too.

The “magnificent system” has struck again.

The Marble Palace

It’s 2022 now. Most battles for voting rights seem to begin in Alabama and end here, on one side of this road or the other.

Over there is the United States Capitol.

Over here is the United States Supreme Court.

Above the front door of this Greek temple of American Justice, it says “Equal Justice Under Law” etched into the facade.

Sometimes that’s been true. Sometimes not so much.

Because of its liberal shift in the 20th Century, the court has had a reputation as a guardian for the marginalized. That hasn’t always been the case — more of a deviation from the mean — and lately the court seems to be regressing to its old ways.

Almost immediately after the Alabama Constitution of 1901 became law, a Black Montgomery janitor named Jackson Giles challenged the new restrictions. He took his case all the way here.

Twice.

He lost both times.

It would fall to Congress to restore voting rights to Black Americans. After the Selma-to-Montgomery voting rights marches of the 1960s, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act. But lately, the court has been chipping away at that law, too.

In 2010, Shelby County, just south of Birmingham, challenged the Voting Rights Act’s preclearance requirements. The top court ruled in the county’s favor, ending Justice Department oversight in Alabama and other states with records of voter suppression.

Free of federal supervision, Alabama enacted photo ID requirements at the polls and closed drivers license offices in rural areas, a disproportionate number in the Black Belt before being shamed into a reversal by the media and investigated by the U.S. Department of Transportation.

Today, the Voting Rights Act is under scrutiny again.

And again, the case comes from Alabama.

After the Alabama Legislature passed that district map in four days, plaintiffs sued the state, arguing that Alabama had not given Black voters proportionate representation.

However, fair representation isn’t all that’s at stake, but also the Voting Rights Act itself. An unfavorable ruling from the court could weaken the law’s protection even further.

So here we are, again — passing beneath that promise of equal protection to see whether it holds true.

Since the Dobbs decision reversed Roe v Wade, the building is tightly guarded, although the Capitol Police are polite and helpful when I need directions.

Inside, it’s obvious why this place has been called the Marble Palace. Most of the marble, incidentally, came from Sylacauga. When you walk the halls of the U.S. Supreme court, you tread on Alabama. Everything about it — the columns, the velvet curtains, the rituals of the courtroom staff — invokes a sense of reverence, whether you’re inclined to give it or not.

Once the hearing is underway, however, I can’t help but think I’ve seen something like this before in my younger days covering the Birmingham City Council. Up there are nine men and women behind a wooden dais, a few like to talk more than they listen, and a couple of them I’m not sure are fully awake. All that’s missing is the smug old council president asking his rivals, “Can you count to five?”

Alabama is expected to win. However, those expectations of an easy Alabama victory soften somewhat after the state’s solicitor, Edmund LaCour, begins to speak.

LaCour says the state had no racist intent when drawing its maps, and he argues that no map maker could draw two minority districts if race were not a consideration.

The state favors a race-neutral system.

Just as Alabama did when it turned off race while drawing its maps.

Taking race into consideration would be a violation of the 14th Amendment, he says.

“What I guess I’m a little confused about in light of that argument is why, given our normal assessment of the Constitution, why is it that you think that there’s a 14th Amendment problem?” Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson asks.

It’s Jackson’s second day on the court, but she’s come prepared and she has a lot to say about Alabama’s arguments. She takes LaCour back to the beginning — the men who wrote the 14th Amendment during Reconstruction.

“I looked at the report that was submitted by the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, which drafted the 14th Amendment, and that report says that the entire point of the amendment was to secure rights of the freed former slaves,” she says. “The legislator who introduced that amendment said that ‘unless the Constitution should restrain them, those states will all, I fear, keep up this discrimination and crush to death the hated freedmen.’”

It wasn’t a race-blind or race-neutral system they were trying to protect, she says. Rather, the 14th Amendment, the Civil Rights Act and eventually the Voting Rights Act all took race into consideration. They had to when ensuring equal protection under the law.

“That’s not a race-neutral or race-blind idea in terms of the remedy,” she says.

Justice Samuel Alito, who has been resting his eyes, gently nudges LaCour toward a more defensible position; they refocus the discussion on the practicality of drawing a second majority Black district that is sensibly drawn and “reasonably” compact.

This seems to be the soft, exposed tissue in the law the conservative justices want to poke — more likely to weaken the law than to completely overturn it.

Justice delayed is justice denied, but look about the building and you’ll find a number of graven turtles among its marble — a deliberate reminder that justice is slow.

If that message is too subtle, they also sell turtle plush toys in the gift shop.

After an hour and a half of arguments, the court adjourns. Its ruling will come sometime before next June.

No time like the present, except the past

It’s not unusual to see federal judges suggest arguments no one before them has considered. I’ve seen it many times.

More than a century after the Alabama Constitution of 1901 became law, U.S. District Judge Lynwood Smith wrote an aside in an order, pointing to a weakness that should have been obvious: If the vote to ratify the constitution was a fraud, isn’t the law a fraud, too?

“Without such criminal acts committed by a white elite in the Black Belt counties, the document presented to the people as the 1901 Constitution would not govern the State today,” Judge Smith wrote in his 2011 ruling. “The evidence of this fact, both in this case and in reliable secondary sources that address the matter, is overwhelming.”

However, the plaintiffs in that school funding case hadn’t made that argument. Writing between the lines, Smith seemed to invite such a challenge.

“As a consequence, this court must leave that issue for another day, and another forum,” he said.

But no one ever took Smith up on his invitation.

In November 2022, Alabama voters approved what they were told was a new foundational law, the Alabama Constitution of 2022.

In reality, the state’s recompilation committee removes the racist sections already struck directly by the courts, but nothing else. The sneaky stuff — the lack of home rule, the broken tax structure, the cruel and capricious education system — was left untouched.

The Alabama Constitution of 2022 isn’t a new document, but an alias for the old one — with the race-neutral racism still firmly encoded.

What’s more, newer discriminatory amendments, such as Alabama’s constitutional prohibition of same-sex marriage, were left untouched.

Constitutional reform groups, which have fought for decades to replace Alabama’s racist source code, rallied behind the effort. They accepted it as a half-loaf, an iterative step toward a long-term goal.

But Alabama’s “new” constitution will ensure the race-neutral racism of the “old” one will live on.

It’s another whitewash. The rot beneath is still there.

I won’t argue that it was the committee’s intent, but this is the risk of not minding one’s history. The power of race-neutral racism is that it works so well, well-meaning folks can perpetuate it without meaning to or realizing it. Like that committee member who questioned whether poll taxes were truly racist, you wind up carrying the baton of long-dead bigots without realizing it, much less questioning why.

That’s why the 1901 convention is so important to revisit. The delegates then were right to worry about the stenographers. That record is their confession. Like action movie villains, they spilled their secret plans, only no hero stopped them from putting their evil schemes into practice. This wasn’t unintentional, incidental or unconscious racism, it was deliberate. They didn’t oppress the poor by accident. That was their design.

They cultivated acrimony and resentment to keep working-class whites and Blacks divided and blind them to the populists’ epiphany — that together they were a threat to the people really in control.

Their plan required not only a social and legal division but a political one, too — a separation that persists today, at the ballot box and in the Alabama State House. Our elected officials call themselves Republicans and Democrats, but Alabama has a white people’s party and Black people’s party. Those partisans in Montgomery spend so much time fighting with each other that they do little to make the state better for the people they ostensibly represent, and it shows.

Every time Alabama lands at the bottom of another national ranking — you can trace a line back to 1901. Power, economic advancement and quality of life were things Alabama’s framers claimed for themselves, not for anyone beneath their social standing. Keeping things as they were — as they’ve always been — suited them just fine. And we suffer for it now as we have since the day they adjourned.Time travel is dangerous in Alabama, but there is one place the Alabama Constitution forbids us to go — the future.

We can zip back and forth, between their time and ours, but until we free ourselves completely from their handiwork — until we rip up that wretched, racist document and write a clean one of our own — Alabama will be chained to its past.