By Megan Sayles,

AFRO Business Writer,

msayles@afro.com

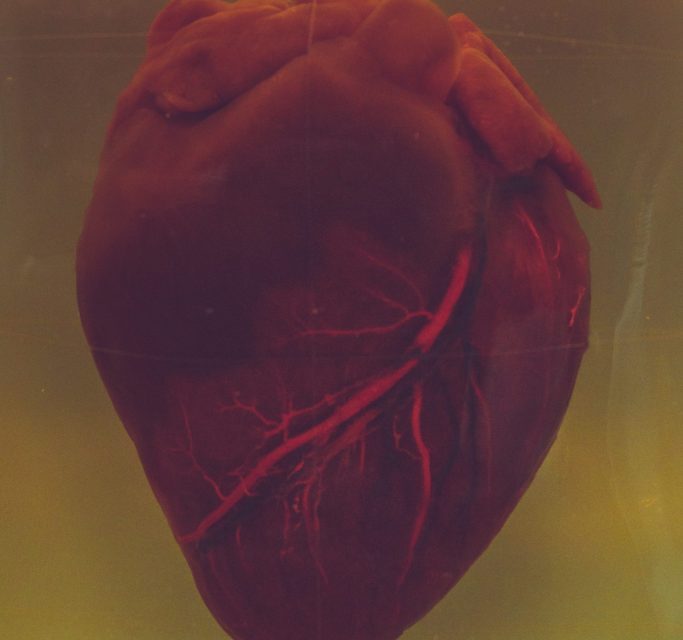

In the United States, the scourge of coronary heart disease (CHD) devours a staggering $108 billion in annual health care costs, according to a recent Deloitte analysis. A disturbing $1.3 billion of this total is tied to health care inequities, according to the same analysis. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) defines CHD as a kind of heart disease in which arteries of the heart fail to deliver ample oxygen-rich blood to the heart. But, it’s not just a clinical entity—it is a mirror reflecting the narrative of inequity in American health care and society.

Baltimore, like many other cities, is trapped in this narrative. Heart disease holds the unfortunate dubious distinction of being the top cause of death in the city, resulting in 1,540 lives lost in 2021 alone, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

This deadly scenario becomes even more ominous for Baltimore’s Black population, which faces a markedly higher risk of mortality.

According to the Baltimore City Health Department, the heart disease mortality rate for Black people was nearly 1.4 times the heart disease mortality rate for their White counterparts. Of those 1,540 heart disease-related deaths reported by the CDC, 1,130 were Black residents and 410 were White.

Inequities in heart disease for African Americans exist for a number of reasons, including increased risk factors, gaps in accessing care, medical mistrust, and food insecurity, according to the American Heart Association. Without remedy, these disparities can cause excess health care spending, decrease health care systems’ productivity and have a broader impact on the overall health and well-being of the larger population.

Heart disease inequities in Baltimore

In urban areas across the country, neighborhoods can impact not just a person’s overall health, but their life expectancy. Baltimore is no exception.

ZIP codes are linked to residents’ social determinants of health, or the economic and social factors that affect health outcomes, according to the Deloitte analysis.

“In Baltimore, because of the social determinants of health, where you live can sadly determine how long you live. ZIP codes just five miles apart can have a difference in life expectancy by as much as 15 years,” said Tracy Brazelton, executive director for the American Heart Association of Greater Maryland.

Where someone lives can also impact people’s access to healthy food, employment, health services, and places to exercise.

In Baltimore, neighborhoods with predominantly Black populations tend to fall short when it comes to these necessities, and they have lower life expectancies.

For instance, in the Upton/Druid Heights neighborhood, 93.3 percent of the population is Black, the unemployment rate is 22.3 percent, the median household income is $15,950, and 26.3 percent of the community is covered by a food desert—areas where residents lack access to affordable, healthy food— according to the city health department’s 2017 Neighborhood Health Profile.

Meanwhile, in the Greater Roland Park/Poplar Hill neighborhood, 82.6 percent of the population is White, the unemployment rate is 2.3 percent, the median household income is $104,482, and there are no food deserts, according to the city health department.

Heart disease was the No. 1 killer in both neighborhoods in 2017. But the heart disease mortality rate in Upton/Druid Heights was 39.1 deaths per 10,000 individuals compared to 13.6 deaths per 10,000 individuals, according to the health department’s Neighborhood Health Profiles. And average life expectancy in Upton/Druid Heights was 68.2 years compared to 83.9 years in Greater Roland Park/Poplar Hill.

According to Athol Morgan, M.D. and M.H.S., obesity and unhealthy diets are critical risk factors for heart disease. He said that unhealthy diets are also a significant risk factor for hypertension, which can lead to heart disease.

Morgan, a member of the American Heart Association’s board of directors for Greater Maryland, says the organization recently assessed the heart-healthiness of 10 common dietary patterns. The top-rated patterns were the Mediterranean diet, vegetarian diet, pescatarian diet and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet.

But, in predominantly Black regions of the city, it may not be easy to obtain or afford these foods.

“If you look at the foods listed in these diets, you can’t easily collect them in West Baltimore. And if you do, it’s more expensive than buying fried chicken and potato chips, which people tend to buy to get the calories they need from day to day,” Morgan says.

In addition to poor access to healthy foods, Morgan says poverty and crime can affect a person’s ability to exercise, which can also lead to heart disease and a higher incidence of heart disease risk factors.

“It affects the poor more because the rich can afford to purchase a gym membership, and they have safer neighborhoods to walk in,” Morgan says.

Accessing care and the role of medical mistrust

According to the Commonwealth Fund, a national philanthropic foundation and think tank, American medicine has had an extensive history of mistreating African Americans, from medical experiments on enslaved people to the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male, in which Black male participants did not give informed consent and did not receive treatment. These previous experiences, combined with more recent encounters with racism and bias, have led to mistrust between the Black community and hospitals, doctors, and nurses.

Dr. Laurie Zephyrin, senior vice president of advancing health equity at the Commonwealth Fund said building trust is essential to advancing health equity.

“It’s more than just saying, ‘They have to trust us,’ because when you say that, you’re already putting a wall between who they are and who we are,” Zephyrin says.

“When I think about trust, I think about what health systems are building in to ensure equity and high-quality health care. If an organization is continuously providing low-quality outcomes, treating people with disrespect, or not listening to people, that is not going to build trust.”

Much of the Commonwealth Fund’s research focuses on how health systems can improve care for disenfranchised communities. Zephyrin says they’ve found negative experiences with health care providers can cause individuals to avoid doctors’ visits altogether and even lead them to forgo doctors’ treatment recommendations.

She also called attention to inequities in health insurance coverage between Black and White people. In the U.S., Black people have lower rates of insurance coverage, according to Zephyrin, making it challenging to access affordable care.

Even with insurance, it’s possible that a person may struggle to access care because of their geographic location. Some may live in provider deserts and not be able to easily engage with health systems or primary care doctors, according to Zephyrin.

“I think it’s important for health systems to look inward at their policies and practices to really better understand how racism, discrimination and bias is manifesting,” Zephyrin says.

A local organization’s fight against heart disease

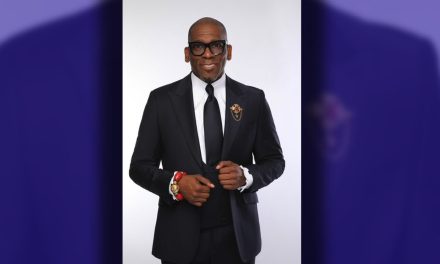

After becoming frustrated with the toll heart disease was taking on his patients, in 2000

Dr. John D. Martin, a vascular surgeon, established a local Dare to C.A.R.E. program. He wanted to raise awareness about heart disease and provide communities with free access to education and screening tools.

C.A.R.E. stands for carotid artery disease, abdominal aortic aneurysm, renal artery stenosis and extremity artery disease, all diseases that affect the heart. The program runs under Martin’s Maryland-based organization, the Heart Health Foundation, and it’s spread to several hospitals across the country.

Today, it offers free health screenings to individuals over the age of 60; individuals with hypertension, high cholesterol, smoking history and family history over the age of 50; and individuals with diabetes who are over 40 years old.

The Heart Health Foundation’s screenings include blood pressure tests, risk assessments, ultrasounds of the carotid arteries and abdominal aorta and blood flow measurement.

“With that information, we’re able to risk-stratify people. We determine whether they have a disease or not and then the severity of the disease they have,” Martin says.

“We share that information immediately with patients and then send it back to their primary care doctors. For anybody who has critical disease, we call the doctor personally and make sure that the connection is made, so nobody falls through the cracks.”

The organization also hosts lectures about heart disease risk factors, like hypertension, diabetes, and high cholesterol.

Years ago, Martin noticed the vast majority of people who were taking advantage of his services were White. So, he decided to learn more about the level of mistrust between the Black community and health care systems, and he connected with local Black physicians to help engage more Black patients.

“In February, we had a really big push because the mortality rates for cardiovascular disease have spiked after coming out of COVID-19,” Martin says.

“It’s because people stopped going to doctors and didn’t go to hospitals, and that has been exacerbated in the Black community where the disparities in outcomes between Black and White people are already huge.”

In February, the Heart Health Foundation hosted a screening day in every Maryland county, servicing more than 1,000 people. The nonprofit also hosted a seminar on heart disease disparities in communities of color.

“We have to acknowledge that health disparities exist for [African Americans]. We can’t just brush it aside and pretend it’s not there,” said Martin. “We have to establish trusting relationships with those in the Black community, and we have to be in it for the long game.”

Megan Sayles is a Report for America Corps member.

This article, inspired by Deloitte research, is part of a series in which five Black-owned publications around the United States explore how health inequities impact racial and ethnic minority groups.

The post Heart disease: Black Baltimore’s number one killer appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers .