By AFRO Archives

The battle to integrate three Baltimore high schools took place in the shadow of the landmark Brown decision in 1954.

“The Association does not intend to endorse the principle of segregation; but to fight segregation by making it so expensive to the State that there will be a disposition on the part of the taxpayer to do away with it.”

— Charles Houston, the NAACP’s special counsel in a 1934 memorandum

This strategy was still at the core of the NAACP’s struggle for equality in education for Blacks in 1954, 20 years after Houston wrote about it and four years after his death in 1950.

Led by Houston and Thurgood Marshall, the NAACP kept pointing out the inequality of the nation’s educational system from the college to the elementary school level, reducing the law of the land of separate, but equal to a fallacy.

“Houston believed that the way to destroy separate was to make it impracticable, make it too expensive and too troublesome,” says Larry S. Gibson, professor of law at the University of Maryland.

This is where Black America stood at the threshold of the seminal 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kan., decision.

For 20 years after the Murray win over the University of Maryland in 1935, the first school desegregation victory in the country, the NAACP chipped away at separate, but equal. Many of those precedent-setting cases took place in Maryland, and established the foundation for the Brown decision.

From 1952 to 1954, while the nation’s focus shifted to Brown, Maryland still played an important supporting role in the final stage of smashing separate, but equal.

OPENING UP THE “A” COURSES

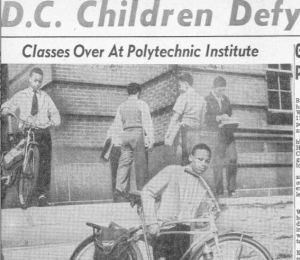

In 1952, the prestigious “A” course at Polytechnic Institute High School was the college preparatory gem of the Baltimore City Public School System. It included courses that would enable male high school graduates to enter college with sophomore status. However, it was only available to Whites.

Thus, Poly was the perfect target for the NAACP’s onslaught against segregated schools. There was clearly nothing equal to the “A” course for Black students, and this was the dilemma facing the Baltimore City school board.

The Baltimore branch of the NAACP assembled 16 elite Black students to apply for the ninth grade “A” course. Once the Black students applied, city school superintendent Dr. William H. Lemmel decided that 10 of them were definitely qualified and three were probably qualified to enter the “A” course. The other three had already completed the ninth and 10th grades in junior high school, so Dr. Lemmel said they probably wouldn’t benefit from repeating course work just to qualify for the “A” course. Nevertheless, the school board faced this question: Would it be possible to create an “A” course for Black students at Douglass High School equal to the Poly “A” course? On Sept. 2, 1952 the city school board held a special meeting to resolve the matter. The meeting lasted about four hours and individuals for and against creating an “A” course at Douglass spoke. Speaking first, Dr. Lemmel asserted that the school board could provide the same curriculum and instruction comparable to the Poly “A” course at Douglass. He conceded, however, that Douglass was overcrowded. Earlier in the summer Dr. Lemmel, in a letter, had admitted it would be very difficult, if not impossible, to reproduce the specialized equipment that was such an integral part of Poly’s “A” course at Douglass. The last speaker in the meeting was Thurgood Marshall, NAACP counsel, who was one of the main litigants in the landmark Brown case. With Charles Houston as his mentor, Marshall was one of the architects of the legal strategy that provided the foundation for the pending Brown decision. As a native Baltimorean and as a graduate of Douglass High School, Marshall may have felt he had a personal stake in the case for him to appear at a school board meeting at the time of the most important case (Brown) of his career. He argued that the board simply had to provide the Black applicants equal educational opportunities.

He also said the Douglass option was a “gamble” … and “a gamble is not what I consider equality.”

At the end of the meeting, a majority of the school board – five members – voted that Douglass could not provide an equal educational opportunity for the “A” course applicants, so they would be admitted specifically to Poly’s “A” course curriculum (full integration of Poly came after the Brown decision). Although the integration of the Poly “A” course did not come as the result of litigation, it was significant because it was the first school desegregation victory in the United States below the Mason-Dixon line at the high school level.

It was a different situation for Baltimore’s Western High School. Twentyfour Black girls who were “qualified” to enter Western – as determined by Dr. John Fischer, superintendent of Baltimore City schools – were denied admission to the elite school in 1953. The board’s action – rather, inaction – in the case of the Western applicants sparked legal action by the NAACP, but the legal outcome of the Western case stayed in limbo until after the Brown decision in 1954. Western, an all-girl school known as Poly’s “sister school,” like Poly was a prestigious all White high school. Also like Poly, the main reason Western was so coveted was its college preparatory curriculum, which afforded college credits for Western’s graduates, and, again like in the Poly case, there was no Black school with a comparable curriculum. This was important to many Black families, who had aspirations for their daughters to attend college.

One of those families was the family of W.A.C. Hughes, the NAACP’s lead counsel in Maryland. His daughter, Alfreda Hughes, was among the first Black students admitted to the school in the fall of 1954, after the Brown decision.

“My father was elated, and my mother. That’s when he made the move to take me up to Western. They were all elated. It was a victory won,” remembers Alfreda Hughes, who says her father took her to the school himself to enroll her.

But her memories of that first day of school are not ones.

“What I remember was the English teacher and French teacher. They didn’t like us very much. They didn’t like the fact that we were there,” says Hughes. “I gave her a smile and she gave me a glare. We were seated near the back and I remember her saying, `I don’t see why people don’t stay where they belong.’ They didn’t want us to go to college, evidently.”

Although her memories of Western are at best mixed, Hughes fully understands the importance of the presence of her Black classmates in 1954 and the work her father did in the Western case and many of the cases leading up to the Brown decision.

“Juanita Mitchell said, `your daddy was the brains behind our cases. We never made a move without calling him,’” recalls Hughes. Mitchell, a political activist going back to the early days

Help us Continue to tell OUR Story and join the AFRO family as a member – subscribers are now members! Join here!

The post From the AFRO archives: On the brink of Brown appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers .