By Tamara Ward

Special to the AFRO

School resource officers (SROs) and zero-tolerance policies have long shouldered the blame for the disproportionate introduction of Black and disabled students into the school-to-prison pipeline.

“I see the pipeline. The pipeline is alive here – alive and well, in this county,” said Melissa Feliciano, an assistant public defender with Maryland Department of the Public Defender in Harford County for 22 years. “When you’re here for this long, you work with a kid who’s 12 and then you turn around 20 years later, they’re in prison–not local jail–they’re in prison.”

“Often it’s an overlap. You have kids on [Individualized Education Plans (IEP)] who are Black – it’s like a double whammy. If you have an IEP and you’re Black, you could be easily screwed in school, screwed out of school,” Feliciano added.

She shared a host of challenges for a student once arrested, coming out of placement or charged with a school fight, which includes ending up in a virtual alternative school or being blacklisted by the school system so that they cannot socialize or engage in positive extracurricular activities.

Feliciano said there was a definite increase in school fight referrals over the last 20 years as well as a steady increase in fights going straight to court, rather than being handled by the school system.

“You can feel it. It’s very palpable because you’re looking at your docket and you’re like, ‘These are all school fights. What’s going on? Why isn’t the school doing what it’s supposed to do?’” Feliciano said, noting Harford is notorious for overcharging for school fights.

She said many are unresolved bullying cases where parents have pleaded with the schools to intervene, to no avail.

“And then it erupts into a one-time incident where our clients end up beating the crap out of someone because they never got help from being bullied,” Feliciano added, noting the bully ends up being the “victim” because the actual victim of bullying was not helped.

Of Harford County’s 115 school-based arrests last school year (2022-2023), 44 arrests were for fighting, according to state data released in March. The good news? That is down from 75 fight-related arrests the year before.

SROs in schools met with skepticism

In reviewing her cases over the last two years, Feliciano determined that not only are SROs arresting students in school, but local law enforcement are calling on SROs to help identify children involved in fights and other incidents.

“Oh, they should be out of there,” Feliciano said, referring to SROs. “It’s just like putting a school cop in there, just for kids to get more charges. That’s basically what it is.”

In her jurisdiction, SROs were the arresting officers in 111 instances and, inclusively, made 104 of those referrals to the Department of Juvenile Services (DJS).

Statewide, this past school year, 2022-2023, SROs were responsible for referring 865 of the 1,568 cases to DJS, according to recently released arrest data from Maryland State Department of Education (MSDE). Local police officers initiated referrals to DJS for 274 school-based arrests. Twenty-nine referrals came from school administration. The remaining 400 were unidentified.

In the prior school year, SROs made 956 referrals to DJS, whereas “Local Police Officers” accounted for 282 referrals. More than 888 arrests did not specify the referring personnel.

The 2018 Safe to Learn Act requires adequate law enforcement coverage within each of Maryland’s public school districts. Providing adequate coverage can consist of full-time SROs within the school or law enforcement conducting safety checks in the school’s patrol area.

In 2022-2023, there were 427 SROs in Maryland public schools. Only 273 schools had full-time SROs, and 1,127 had law enforcement coverage in other ways, according to the state’s 2022 Annual School Resource Officer – Adequate Coverage Report.

That represents a decrease of 18 schools from the year before, when 291 schools had full-time SROs, while 1,128 had adequate coverage provisions [2021-2022 report]. That year there were 422 SROs.

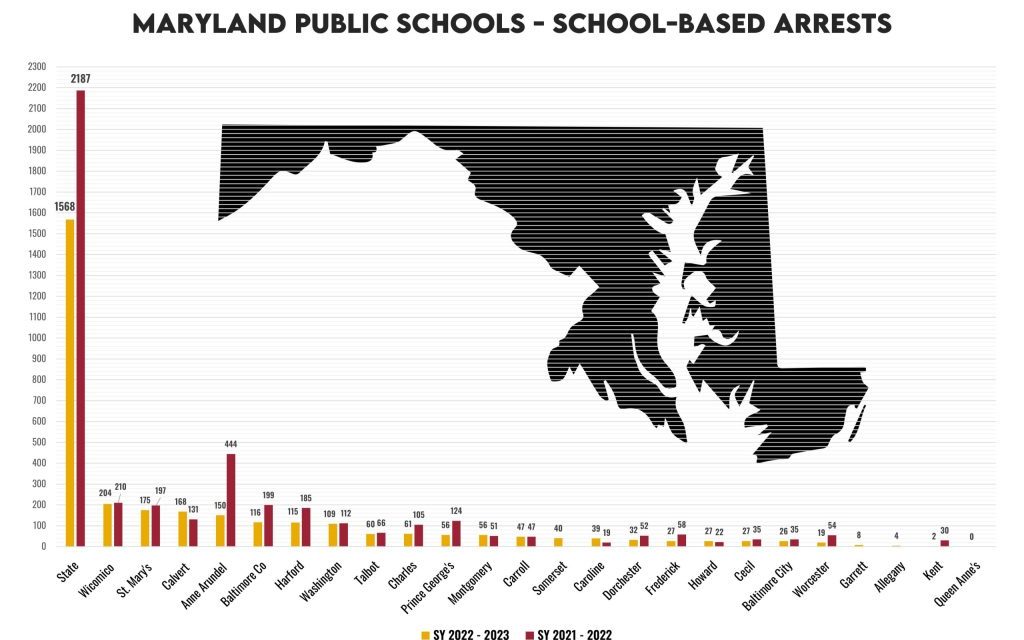

As more schools opted for adequate coverage instead of a dedicated SRO within the school for 2022-2023, arrest numbers across the state dropped by 28 percent, from 2,187 to 1,568.

Avery Berdit, a recently retired assistant public defender, defended numerous students who were entered into the school-to-prison pipeline by SROs and local law enforcement.

Berdit said for the bulk of his career he worked in juvenile courts by choice. Although his jurisdiction included Baltimore and Carroll counties, the majority of his work was in Howard County, handling indictments, felonies and district cases.

“So, I did a little bit of everything,” said Berdit, who estimates his career caseload numbered in the tens of thousands, with 80 percent of the youth he defended being students of color.

It was not uncommon for Berdit’s school-related juvenile client caseload to arise from an officer arresting a student.

He recalled that one student he represented, who was on an IEP, was told to do something in school by a police officer and the student responded, “No!” Berdit said the officer’s response was to treat it like a law enforcement issue.

“Ultimately, the kid’s thrown down. The kid runs out of school. He gets charged with disorderly [conduct]. He’s charged with resisting [arrest],” Berdit said. “And he wasn’t a bad kid. He was a kid that didn’t have any contacts with the system.”

This type of outsized response happens frequently, he said.

“Even teachers or school security guards that don’t know about this kid’s IEP will treat [him or her] in a way that’s not consistent with [his or her] therapeutic needs. And, as a result, you get a response that is not a response they expect. It’s a response from a kid with a disability. You don’t criminalize that. You don’t call the police. Or you don’t contact the SRO saying, ‘We have an out-of-control kid,’” Berdit said. “When you’re dealing with a kid, who may be culturally different than you, who may have a disability that you don’t know about, there’s a way to treat those kids. Getting in their face and saying ‘You do this, you do that’ – it doesn’t work. And, if a kid is defiant, that may be consistent with their emotional or psychological issues.”

Berdit said one of the things that used to “gripe” him about SROs is how they bide their time during school hours, which he calls systemic.

“Think about that. They have eight hours a day. They’re not teaching classes. If they’re in the schools, there aren’t too many school emergencies, especially out in Howard County. So, what are they doing during the day?” Berdit questioned. “By their own [Memorandum of Understanding with the school system], they’re surveilling. They’re looking at kids, and what they see they report to other police officers.”

Berdit said one of the SRO’s primary purposes is to gather intelligence and provide it to their colleagues, which may lead to arrests outside of school.

“They’re made aware of these kids out in the community, and sometimes they’ll use that to establish probable cause; sometimes they’ll use that to stop kids,” he said.

“We have kids that are marked. They’re Black kids and brown kids,” Berdit said, explaining that assumptions about a kid’s reputation follows him or her into the community. “Police officers will pull kids up. ‘What are you doing? This is what I hear about you. I hear you’re dealing drugs.’ That is not atypical.”

He struggled to recall any positive interactions his clients had with SROs and law enforcement.

“I’ve never ever represented the kid who said, ‘Yeah, this SRO or this officer so-and-so helped me out. Officer so-and-so gave me a ride to school. Officer so-and-so helped me get involved in youth activities.’ Never have had that. Never ever,” Berdit said.

He estimates that in Howard County, in every 10 cases, he would get a school-related suspension or school-related offense case where an SRO was involved. He acknowledged sometimes SROs were not involved.

“But the SROs, when they got involved, they didn’t really ameliorate the situation. Sometimes they exasperated it,” Berdit said. “Because they’re trained law enforcement officers,0 and that’s what they’re trained to do.”

Berdit said police officers should make positive contacts in their communities, assist kids with getting to school and ensure kids comply with probation rather than constantly violate it.

A skeptic of the idea that having police officers in schools prevents school violence and mass shootings, Berdit said, “I think the practical reality of all the school shootings, school officers couldn’t have prevented those things.”

Former Howard County teacher Erika Strauss Chavarria, who questions why SROs are in schools, also doubts they can prevent shootings.

“Some may say that they’re there to keep the school safe from shooters. However, we know that the data shows that police officers do not. They actually have a miserable failing record in terms of stopping or preventing a school shooting,” Strauss Chavarria said, pointing to reports of police response during the Parkland and Uvalde school shootings in Florida and Texas, respectively..

“They are also not required by law to interfere in a school shooting,” Strauss Chavarria said.

Maryland State Education Association (MSEA) and its 75,000 members consisting of teachers, education support professionals, certified specialists and school administrators have mixed feelings on whether SROs should be in Maryland’s public schools.

MSEA President Cheryl Bost said some educators and students have great relationships with security and SROs; they feel safe and they feel the administration utilizes the security appropriately.

And due to the nationwide rise in mass shootings, gun proliferation and other safety concerns, Bost said some members feel law enforcement should be on campus, “but they feel that they should absolutely not have any interaction with students in a disciplinary manner.”

“If they are going to be there, they should be protecting us, basically, from the outside negative forces or if … a gun comes into the building,” Bost said. “They shouldn’t be there dealing with students; the administration should be dealing with students.”

MSEA’s posture is very different from that of the National Education Association (NEA), which is in full support of removing the criminalization and policing of students in schools and believes the practice perpetuates the school-to-prison pipeline.

Among NEA’s guiding principles is the elimination of disparities in disciplinary practices, which includes eliminating zero-tolerance policies that criminalize minor infractions.

Bost said MSEA’s position differs from NEA because of the adequate coverage law in place in Maryland. And since SROs are in Maryland schools, MSEA is working to ensure they receive anti-bias and de-escalation training.

And while she recognizes SROs are a deterrent to extreme violence from the outside, she acknowledges teachers and administrators become overworked, and in turn they sometimes rely on those SROs to deal with disciplinary matters.

“We feel wholeheartedly that there is a lack of training, time and opportunity within a daily schedule, and too many kids in the class for teachers to deal with the root causes of the disruption of some of our students,” Bost said, citing a possible overdependence on SROs.

In instances where students get into an altercation, instead of the administration handling it and issuing the students detention, suspension or a required parent conference, if an SRO is involved and their police code tells them that it is an assault, the officer has to bring about an arrest.

“That would not be taking place if they weren’t in the building,” said Bost. “And that is what we believe contributes to the school-to-prison pipeline, that they’re there. So, they’re used. And it shouldn’t happen that way.”

During her 12-year career as a Spanish teacher, Strauss Chavarria said she saw firsthand SROs enforcing school policy, and after they witnessed fights, the SROs charged students with assault and battery.

She said discipline issues that used to be handled by the principal’s office or through mediation and “just talking it out” are now arrestable offenses.

“We have essentially criminalized young children up to high school age, before they even enter the building,” Strauss Chavarria said. “So, anything you see an officer do on the street, they are required to also do in the school,” per most MOUs between school systems and law enforcement agencies who provide SROs.

She acknowledges there are plenty other reasons why students are being arrested that have nothing to do with “disciplinary matters,” but she feels the mere presence of a police officer and SRO in a school building does increase the school-to-prison pipeline, because they are required to do their job.

“So many of these offenses are subjective, it depends on the perception of the teacher, or the perception of whoever is stopping the kid or whatever the issue is,” Strauss Chavarria said.

A disparate system for Black, brown, disabled, and neurodivergent youth

To Strauss Chavarria, the disparity of arrests is most concerning.

“All of the data shows that the presence of police officers in schools has had a drastic impact, and disproportional impact on Black and Brown students, has funneled Black and Brown students into the prison system, and that is in every county,” Strauss Chavarria said, pointing to multiple years of MSDE arrest data.

And while Howard County does not rank in the top 10 of school districts with high arrest numbers, Strauss Chavarria said Black students with an IEP or a Section 504 Plan make up the majority of arrests in Howard County Public Schools.

In school year 2022-2023, Howard County Public Schools recorded 27 school-based arrests. Eighteen of them were Black students; four were students either on IEP or with a Section 504 behavioral plan.

“So, they are being arrested for a behavior that is already written into a plan that the school should be aware of,” Strauss Chavarria said.

Matthew Vaughn-Smith, founder and president of the Anti-Racist Education Alliance Inc. (AREA), a nonprofit that strives to dismantle White supremacy in schools and classrooms, is also an administrator with Montgomery County Public Schools.

“We want police-free schools. So, no school resource officers,” he said emphatically of AREA, going as far to exclude security assistants from school environments.

Vaughn-Smith recalled a December 2021 incident caught on video where a Howard County Public Schools security assistant allegedly assaulted a restrained student in the cafeteria at Howard High School. The student was allegedly thrown to the ground, pinned down by an assistant principal and an SRO, and repeatedly hit in the head by the security assistant, a school employee.

According to Howard County Police Department reports, the student had assaulted other students. The student and security assistant were both charged. The school administrator and SRO were investigated but not charged. The security assistant was later acquitted of the charge of second-degree assault.

“A school building is a micro community. When you put police in a community there’s going to be more crime because they’re looking for it,” Vaughn-Smith said, echoing Strauss Chavarria’s concerns. “Because when you over-police an area, you’re bound to find more crime.”

He said when a police officer is placed in a school, developmentally appropriate childlike behaviors become criminalized.

“I take the candy bar off a teacher’s desk, that’s now theft, instead of having a conversation with a child about keeping your hands off of stuff that doesn’t belong to you. There used to be a time where we had those conversations,” Vaughn-Smith said.

Addressing the disproportionate arrests of Black students, he said there is racial bias that, when added to a school setting, results in “a lot of Black and Brown babies – surprise, surprise – who are being arrested at school for the same things that their White counterparts may have been doing.”

He said incidents involving White students are handled differently, in his experience as an educator and an administrator.

“It’s a phone call home. Or it’s ‘Oh, let’s have a conversation,’ or ‘Oh, you can go to the front office.’ Not ‘I feel threatened. I need the SRO to come to my classroom. She’s getting loud. I need the SRO to come in here,’” he said.

Vaughn-Smith said teachers and administrators are reluctant to admit that bias exists. “Nobody wants to be told that their unconscious bias is being weaponized. That’s not a conversation that White people especially want to have,” he said.

But that unconscious bias ultimately results in calls for the SRO to handle school discipline matters and the SRO is not likely to say an issue is a discipline issue that would be better handled by the front office, Vaughn-Smith said.

“They’re naturally going to go in there and, quote unquote, ‘help.’ And that help leads to the criminalization of our babies,” Vaughn-Smith said.

And while the disparate treatment of Black and Brown students concerns Vaughn-Smith, he has greater fears about the treatment of students with special needs or who are neurodivergent.

“It scares me that when I see an 8-year-old who has a need, whose behavior is communicating a need, it scares me to think that someone will see him in one of his tantrums or his fits and put him in a cop car,” Vaugh-Smith said, recalling a time when that almost happened to his son while he attended Baltimore City Public Schools.

He said his son had a crisis event and the elementary school called him to say they were going to call their crisis team, which meant a police officer would come and take him to a hospital.

“I said, ‘Absolutely not,’” Vaughn-Smith said, noting he immediately drove from Montgomery County to Baltimore to get his son. “What you will not do is layer that trauma on him by putting him in handcuffs or putting him in the back of a car.”

Vaughn-Smith said thinking about his eldest son, who is neurodivergent and has special needs, “fuels” his work.

“He’s already a Black boy in the public schools. So, his chances of being suspended, expelled, arrested [are great], but now he’s neurodivergent, Black and male in a public school. So, the multiplier is ridiculous.”

Poor academic instruction

While Feliciano believes SROs should not be in school, she acknowledges there are systemic failures also contributing to the school-to-prison pipeline.

“I believe the school system has really failed these kids,” said Feliciano, noting that some students are “promoted socially” to keep pace with their peers despite their low grades, while some are transferred to alternative schools.

To ensure her clients understand the court proceedings, she often requests the court to order a competency evaluation to see if her client is able to stand trial and assist her in their defense adequately.

“A lot of times they can’t because they were pushed through school,” Feliciano added.

Education attorney and assistant public defender Alyssa Fieo believes there is a correlation between low-performing students and disruption in schools.

“I’ve been significantly concerned by the low levels of literacy of some of the older clients I’m representing,” Fieo said, pointing to cases in Anne Arundel and Harford, where she says literacy levels are low, and school-based arrest numbers are among the highest in the state.

In school year 2021-’22, Anne Arundel County Public Schools led the state with a reported 444 school-based arrests. This past school year, the number dropped dramatically to 150 arrests, falling to fourth in the state. Harford County Public Schools logged 115 arrests last school year and 185 in 2021-22, hovering around fifth and sixth in the state ranking.

Fieo attributes increasing literacy rates and decreasing school disruptions and in-school arrests to the curriculum based on the Science of Reading, which some school districts have begun to adopt.

In addition to being a youth defender, Feio is also an advocate. A proponent of restorative practices, when possible, Fieo’s advocacy includes providing testimony in Maryland’s State House on bills that deal with school discipline issues. Currently, she is supporting companion bills that seek to remove from the education code a provision that allows students to be charged with disruption.

Fieo works in the Juvenile Protection Division within the Office of the Public Defender, where she not only focuses on keeping students statewide out of jail, but also advocates for the well-being of confined youth.

“If they are in the community or returning to the community,” Fieo said, these students need to be “set up to have support services that they need to be in school – successful in school – to work their way through the curriculum so they can graduate with a high school diploma.”

The post From homeroom to handcuffs: Part 2 – Resource officers, poor academic instruction blamed for fueling disproportionate school-to-prison pipeline appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers.