By Kelly Kazek

By 1912, John Samuel Barker had convinced more than 70 people living in rural areas along the Lauderdale-Limestone County line that he was Christ. Calling himself the Rev. Barker, the tall, broad-shouldered man who had until then worked mostly as a store clerk began holding religious meetings in brush arbors when the weather was good and in Jim Moody’s general store when it wasn’t.

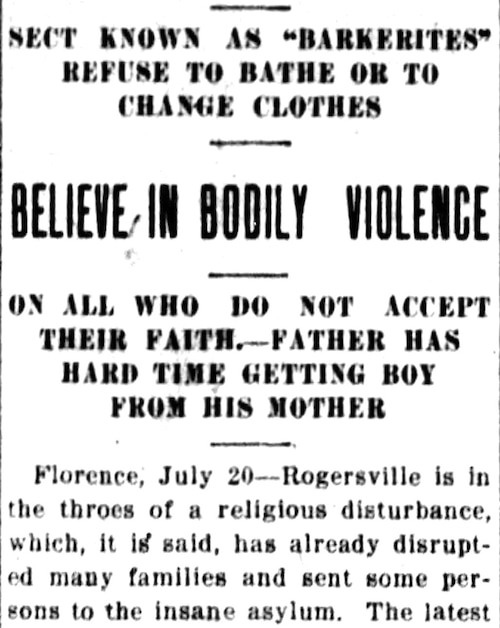

Before his reign as leader of the “Barkerites” was over, Barker would strong-arm his followers to give their belongings as “tithes,” preach violence against non-believers, and be accused of kidnapping and involvement in the murder of his two-year-old great-nephew.

This is the story of one of Alabama’s earliest known cults and its charismatic and terrifying leader.

John Samuel Barker was born to John and Nancy Shoemaker Barker in western Limestone County in November of 1861, just seven months after the start of the Civil War. He grew to be known as an “eccentric.” Still, it wasn’t until he went to Oklahoma in 1900 and began preaching to Native Americans that he realized his words had impact. In fact, he learned he could use the words of the Bible to manipulate people to his own benefit.

A descendant of Barker’s who was interviewed in 2010 said the family passed down tales of their notorious family member. “He knew the Bible from over to cover and could quote any part of it, but he used it for his purpose and not the purpose of God,” said Sally Hess, whose father was one of Barker’s nephews, in the book “Forgotten Tales of Alabama.”

Barker returned to western Limestone County, Alabama in about 1908 and put that knowledge to work. He grew his flock and began isolating them, first by decreeing that it was a sin to bathe and to change their clothing and then that “it is a virtue to assault all who are not believers in his doctrine,” according to a July 1912 article in The Decatur Daily. It was enough to keep even the most curious outsiders away.

But Barker wasn’t satisfied with that. He also taught his followers that the devil would possess one person in each family and that sometimes that “devil” was one of the children. Those who were possessed, he said, should be killed.

“He was a very religious man, but he was an extreme individual,” Hess said. “He always said there was a devil in every family.”

Sometime around 1910, one of Barker’s followers, a Limestone County farmer, was told to kill his pre-teen son who had been deemed the family’s devil, according to lore. The father, unable to hurt his son directly, reportedly put his son inside a stall in their barn with a temperamental mule, hoping the vicious animal would kick the boy to death, an article in a 1962 of The Huntsville Times recounted. The boy, thankfully, survived.

In 1912, a man named Wiley, or Wylie, Hudson sought help in a Lauderdale County court to get his seven-year-old son, Wallace, from the clutches of the Barkerites. According to a July 1912 article in The Tennessean, Hudson’s wife, Josie, was under Barker’s spell. While Hudson was away, Josie Hudson attempted to take their three young children to join the cult. Hudson’s mother, who was watching the children, bravely shielded the two youngest, even when their mother pulled a gun on her. Josie got away with the seven-year-old boy and hid him within the cult. The father was awarded custody of the child after Josie Hudson told the judge she “would leave husband and children and anything on earth to follow Barker,” according to the July 24, 1912, edition of The Gadsden Times.

Lauderdale County apparently tried to distance itself from the cult following the trial, when The Times Daily published a notice in August 1912 stating: “The discussion of this so-called religious sect, located in northeast Lauderdale and Limestone counties, has developed the fact that Barker, the leader, is a Limestone man, and not a citizen of Lauderdale. His residence is on the other side of the line, though a number of his followers live in this county, all in the region of the county line.”

Newspaper accounts at the time said previous attempts at legal intervention failed. The Tennessean said, “The fear of Barker and his followers has prevented any movement to suppress them.” The article also stated that some of those who opposed Barker were committed to what was then known as the Alabama Insane Hospital in Tuscaloosa. “The Barkerite religion has previously separated a number of couple and has sent several of its devotees to the state insane asylum,” the article said. “John Barker, the leader, had been committed to the insane asylum several times. He claims, and his followers believe, that he is the Christ, and they only through his baptism can salvation be attained.”

Finally, in the late 1910s and early 1920s, some followers began to catch on that Barker was not a prophet and he decided to return to Oklahoma, taking a nephew and his wife, Joseph and Letha Barker, and their four children with him. They ended up living in tents in a park in Watonga, Okla., avoided by locals until someone noticed a 2-year-old boy had disappeared from the group. The Rev. John Barker, as well as Joseph Barker, was under suspicion, according to a 1924 article in the Enid, Okla., Daily Eagle.

In 1923, the reverend’s nephew, Joseph, was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to 10 years in an Oklahoma prison in the death of the child, Artemus (some reports name him “Arthur”).

After serving his sentence, Joseph returned to Limestone County and died in 1936. The Rev. John Barker also returned to his roots, although his cult never recovered. He died February 17, 1934, in western Limestone County and is buried there in the Barker family cemetery.