By Hailey Closson,

Capital News Service

“Have you seen the gravesite?” a neighbor asked.

“Seen what?” Amanda Sciaretta responded.

The weather was pleasant the day Sciaretta joined her father and daughter for a walk around her new neighborhood in the fall of 2023.

She and her husband, Anthony, were a few months away from welcoming a member to their growing family, another daughter, and had recently moved from a Maryland suburb to an emerging housing development in King George’s County, Va., called Oakwood Estates. It’s a small rural community in the northern part of the state, complete with farmlands and a bustling nature scene along the Potomac River.

Through her neighbors, Sciaretta learned that her home connected to lurid whispers about an enslaved woman’s grave in the forest.

“We were just walking outside in my neighborhood and people had mentioned that there was a grave in our neighborhood in the woods. As we were walking, we were looking… and we could see it from the road,” Sciaretta said. “We went closer and that’s when we saw the gravesite they had mentioned.”

King George’s County is home to a legion of historic sites including a national trail and the birthplace marker of James Madison, the fourth president of the United States. But lesser-known is the final resting place of a vital figure in the development of gynecological science, an enslaved woman named Anarcha Jackson.

Off the road in the thickets of a shallow preserve stands a polished tombstone adorned with a statue of a cherub, surrounded by several marked and unmarked stone slabs.

“We said a prayer before we approached it because we didn’t want to be disrespectful,” Sciaretta said. “But we looked at it and you could see she had a really nice headstone that looked like somebody put [it] there more recently.”

The burial grounds Sciaretta and her neighbors encountered belonged to a White Reconstruction-era family whose matriarch was named Hattie E. Jackson, according to J.C Hallman, researcher and author of the 2023 biography about Jackson, “Say Anarcha.”

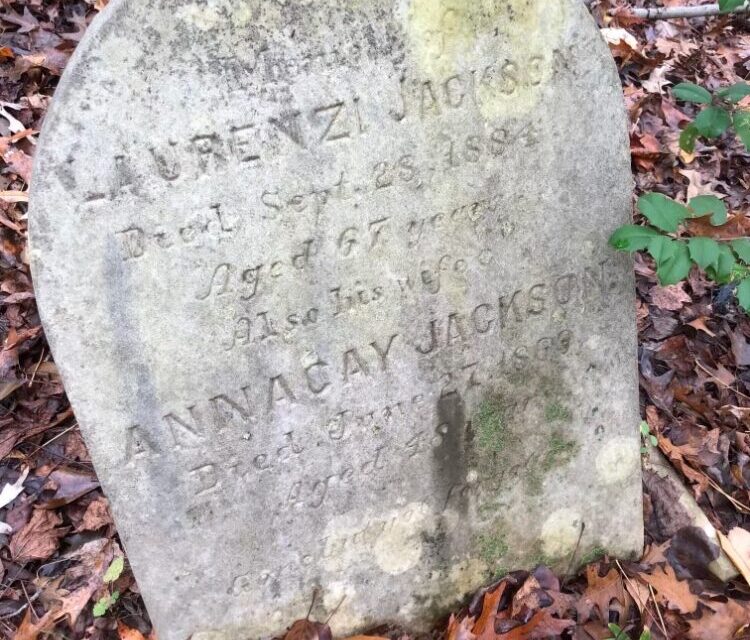

Jackson’s headstone lies further back in the woods, propped against a tree.

Who was Anarcha Westcott Jackson?

Anarcha Westcott Jackson was born on the Westcott Plantation in Alabama around 1828, where she was listed as the fourth of five children, according to some of the earliest birth records found by Hallman.

In 1845, physician J. Marion Sims, the man known as the “father of gynecology,” received a request to visit the Westcott Plantation near his practice in Montgomery, Ala., to perform a forceps delivery on Jackson.

Sims had created a “Negro hospital” in his the backyard of his residence to perform orthopedic and ophthalmological surgeries, according to docuseries, “The Anarcha Archive,” available on Youtube. He conducted experiments at a local infirmary on enslaved men suffering from face and jaw cancers. He also experimented with the infants of enslaved mothers, finding that a diagnosis he called “infant lockjaw” was the bacterial infection tetanus.

It’s estimated that Jackson was 15 or 16 at the time of her pregnancy, which was likely due to rape, as the Westcott Plantation was known for forcing enslaved women to reproduce, Hallman said.

She was in labor for days. After her delivery, she suffered a vesicovaginal fistula, an opening between the bladder and the vagina that causes involuntary urinary incontinence, according to Johns Hopkins Medicine. The abnormality can occur from difficulties during childbirth.

Sims determined Jackson’s condition was incurable, as were the conditions of two other women battling the same affliction, Betsey and Lucy — the only names (minus Jackson) who were listed in his writings about his first round of pelvic experiments. He discharged the women but returned after testing a curative method on a white woman who’d dislocated her uterus from a fall off a pony, according to “The Anarcha Archive.”

Sims gathered Jackson, Lucy, Betsey, and seven additional enslaved women suffering from vesicovaginal fistulas to be the subjects of his and his colleagues’ medical tests in his backyard hospital.

His experiments were conducted without the patients’ consent and without anesthesia, a sedative and pain reliever that, while in its early development, was given to white women, according to Vanessa Northington Gamble, professor of medical humanities at George Washington University in a 2016 interview with NPR.

It is estimated that Jackson underwent 30 procedures while in Alabama and an unknown number of additional procedures after being sold to plantations in Virginia.

Sims founded a women’s hospital in New York in 1855. His assistant married a woman in Alabama, prompting the discovery that the original surgeries Sims performed on Jackson did not cure her. Jackson was sent to Richmond, Va., to be further studied by the founder of a new medical school in the state, Charles Bill Gibson. Gibson was unsuccessful in curing Jackson, pregnant with her fifth child at the time, and sent her to Sims in New York.

The details of her trip to New York are unclear because of insufficient documentation, a common struggle in the research of enslaved people, according to Hallman.

The Maury family of Bowling Green, Va., later “owned” Jackson. Around 1863, she was leased to the “Alto” Plantation, owned by Charles Mason in King George, Va.

A letter between Mason and William L. Maury details that Jackson was in poor health and unable to work. She lived through the emancipation of enslaved people in 1865 and is recorded by the King George’s County Historical Society to have died in 1870 at age 48.

Unofficial marriage records show that Anarcha Westcott Jackson, also referred to as Ankey, Anky, and Annacay in varying historical documents, deemed herself married to a formerly enslaved man named Lorenzo or Laurenzi in 1864, Hallman wrote. Lorenzo is believed to have adopted Jackson’s birth last name and not the name of her first enslavers on the Westcott Plantation. He died 15 years later in 1884 and is buried next to her and two of their infant children in the woods.

Jackson carried 10 pregnancies to term.

The path to memorialization

Jackson’s gravesite rests on private property and no formal arrangements have been made between the county and the landowner.

Nick Minor, the director of economic development and tourism for King George’s County, said the property owner has been cooperative in allowing people to visit the gravesite and helped to confirm it as Jackson’s.

Minor says his department and the King George’s County Historical Society have discussed a project, but are unable to do anything without a formal request and collaboration by the landowner.

“We can’t just interject on this project and take control over it– that’s not how this works,” Minor said. “This has to be a cooperative project from the landowner to the historical society, to the county, and then any other organization that would need to be involved to do this the right way.”

Under a solemn tree, Jackson’s grave will be preserved in its spot and remain there permanently, said Robert Gertz, the president of the company that owns Oakwood Estates. The Rawlings family cemetery will also be preserved as the work in that phase of the neighborhood is completed, he said.

This article was originally published by Capital News Service.

The post Deep in the woods, a former enslaved woman’s grave appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers.