By Ralph E. Moore Jr.,

Special to the AFRO

Although she went to her heavenly reward 141 years ago, Mother Mary Elizabeth Lange, founder of the first order of religious women of African descent, has yet to be properly appreciated for who she was and what she did for others in education, social services and racial justice.

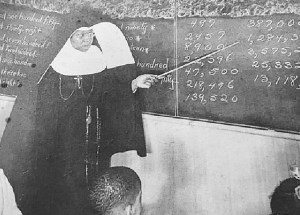

She and the Oblate Sisters of Providence (OSP), the order she started, taught the children of enslaved persons how to read. They did so in a period of our nation’s history when slavery was an institution that denied education to Black and Brown children in America.

Staring down the evil of racism, the Sisters taught children how to read the Bible anyway. They wanted the children to know God.

The Sisters answered to a higher power than the United States government. Their faith informed them that everyone is equal in the eyes of God. Bear in mind, public school education is older than America itself–the country came to order in 1776. There was a school established in Boston in 1635, not long after enslaved persons arrived in 1619.

Centuries later, Mother Lange and the Oblates risked their lives and safety when they opened the school that would become St. Frances Academy in Baltimore, in 1828.

Because of her commitment to educating the most marginalized, the lawfully ostracized, the poorest members of society, a strong case can be made for Mother Mary Lange being considered the mother of education for all in the United States.

She and the Oblates extended religious life to those excluded by racial prejudice and discrimination; they created a Catholic organization wherein people of color could become Sisters. And they continued to educate children once they formally became nuns. But it was not easy in the pro-enslavement, racist, sexist, anti-immigrant, and anti-Catholic prevailing sentiments of the day.

Mary Elizabeth Lange was born Elizabeth Clarisse Lange in the French quarter of Santiago de Cuba. The Maryland State Archives puts the year of her birth as 1789. Her family was well off and were high society people, but they were refugees running from conflict in San Domingo, Dominican Republic. Because of that fact, she was well educated. She departed Cuba for the United States when she was a young girl. She first landed in Charleston, S.C. but worked her way up the east coast to Baltimore by 1813.

Once here, Elizabeth Clarisse Lange became aware of a population of French-speaking immigrants from Haiti who had fled their homeland during the Haitian Revolution against the French between 1791 and 1804. The children of those Haitian families had no public schools they could attend and so Mother Lange and three other Black women began to teach the children. Their names were: Madeleine Balas, Rosine Boegue and Therese Marie Duchemin. Their original mission was to educate girls only, for free and in Lange’s home.

Eventually in 1828, Mother Lange received a request from Archbishop James Whitfield of Baltimore to open an actual school for girls of color. He sent his proposal to her through Father James Hector Joubert. Lange ultimately expressed her wish to enter religious life –she wanted to become a nun. The problem was no existing religious order in the United States would accept a woman or man of color. Their idea and image of God were made in their self-image of White supremacy, so the four women educators were left out of becoming Sisters in the Catholic Church.

Nonetheless, they continued to teach as the priest and the sisters applied to start a religious order for women of color. They petitioned the Pope and in 1829 they were approved by Pope Gregory XVI and on July 2, 1829, the Oblate Sisters of Providence were born. They took their first vows. Lange became known as “Sister Mary,” and later, Mother Mary Lange.

They were great educators in all subjects– then and up to this day. So, I asked a couple of students taught by the Oblate Sisters what their time spent in the classroom with the nuns really meant.

Reverend Nancy M. Dennis, a pastor in the AME Church

“The OSP left an indelible imprint upon my life and in the lives of my two late brothers. The spelling, penmanship and diction drills had a lifelong impact on our articulation. The Oblates reinforced our parents’ teachings about our self-worth and how to appreciate our Blackness in a Eurocentric society. We were never to think less of ourselves due to our ethnicity. Being African American is a source of pride. We were challenged to be our better selves by positively impacting our community. The OSPs impressed us to be responsible for ourselves and for others. We learned to think critically, as well as when to be radical or judicious. The OSPs and our parents stressed the need for fortitude to persevere and even prevail over the perennial adversities in life.

“My siblings and parents are now resting with the ancestors along with many of the Oblate Sisters who taught us. The disciplines of prayer, reflection and fasting learned from the Sisters remain with me today. All the formal and informal instructions from them prepared me to achieve academically and to be impactful in the various positions I have held as a public servant and in ministry. My gratitude extends to the many remarkable women of the OSP for their selfless sacrifices to educate, love and care for students like me. Finally, I was blessed with some of the finest schoolmates one could have while attending St. Pius V Roman Catholic School and St. Frances Academy, where the Oblate Sisters taught.”

The Oblates’ quality of education led Rev. Dennis to an impressive life of public service, which includes: Parole Commission Administrator, Coordinator for the University of Maryland School of Law Clinical Program, Jury Commissioner for Baltimore City (the first Black in this capacity), and for many years Pastor in the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Judge William McKinley Jackson, retired, of the District of Columbia Superior Court

“There is so much about them that can’t be distilled into a few words,” Judge Jackson said, then adds, “My first encounter with the Oblates was the day I entered St. Pius V in the Third Grade. My teacher was Sister Justina Matthews [It is hardly surprising to me that I remember each of my teachers at St. Pius, but struggle to remember names of all of my high school (Loyola Blakefield), college (Brown University), and law school (Harvard Law) teachers]. I was not Catholic, but the Oblates treated me as one of their own. I felt the love even though I was occasionally referred to as ‘the non-Catholic.’

“St. Pius was not the first time I had had African American teachers. I had come from P.S.114, Harriet Tubman Elementary School, a fully segregated school in a mixed neighborhood. However, the Oblates had an end game. They drilled the basics academically, but embraced the new academic disciplines: New Math, new science discoveries. They did this without the same level of resources of the White Catholic schools in Baltimore. I could go on, but suffice it to say, I owe much of my success to those wonderful Oblates.”

Proper recognition of Mother Mary Lange within the Catholic Church is long overdue

The founder of the Oblate Sisters of Providence, Mother Mary Lange, is not recognized as a saint in the Catholic Church. Incidentally, no Black American from the United States is a saint while there are 11 White American saints. For all the groundbreaking she did, all the courage she mustered with the other Sisters to face down wrongdoing and disease, including the cholera plague in 1932 she kept the faith. And for all the disrespect she was shown by other religious figures, clergy and the like. Lange kept that faith and stayed in the remnant, dutifully “doing the will of God.” For all of that, she receives little recognition from her church. Is it because, as the saying goes, “No good deed goes unpunished?”

Church officials say she is in “the process” of canonization. And Black Catholics and supporters say that it is wrong to continue to neglect her. When it is wrong now, they say, fix it now. Sainthood delayed is sainthood denied. And for current White supremacist Catholics, they may take the appearance of apartheid within the U.S. Communion of Saints as a relic or keepsake of historic racial segregation and oppression in the Catholic Church. It is time for the Pope to say, one can no longer consider oneself a good Catholic and a White supremacist at the time. So, pick one.

Mother Lange and the Oblate Sisters of Providence have helped a whole lot of people. And it is time to give Lange the respect she has long deserved.

The post Courageous and committed educators: Baltimore’s Mother Mary Lange and the Oblate Sisters of Providence appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers .