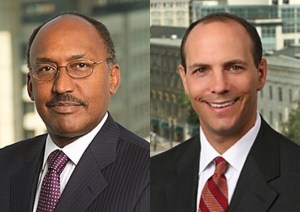

By Kenneth Thompson, Consent Decree Monitor

Seth Rosenthal, Consent Decree Deputy Monitor

In recent years, especially after the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police, demands for police reform have figured prominently in our national conversation and fueled a rising movement for racial justice. You don’t need to look any further than our own city, however, to see how policing can be reimagined. Because of a comprehensive “consent decree” entered into by the Baltimore Police Department, the city of Baltimore, and the U.S. Department of Justice in April 2017, Baltimore is ground zero for police reform in the United States.

The consent decree is a federal court order that requires BPD and the city to implement many of the measures reformers nationwide are advocating: limitations on the use of force and obligations to de-escalate, alternatives to arrest for low-level offenses, diversion of youth offenders from the legal system, and responding to individuals in crisis with behavioral health professionals instead of or alongside police, to name a few.

The consent decree also obligates BPD to overhaul its infrastructure—from training and recruitment to technology and internal affairs investigations—to become a modern, data-driven, self-correcting agency.

The objective of the consent decree is constitutional, community-oriented policing that preserves public safety while revitalizing police-community relations.

Federal Judge James K. Bredar supervises implementation of the consent decree. He will determine whether and when BPD and the city achieve compliance and can be released from court oversight.

Judge Bredar is assisted by a monitoring team. We lead that team, which includes experts in policing, civil rights, behavioral health, organizational change, and community engagement. As Judge Bredar’s “eyes and ears,” our team members provide BPD and the city technical assistance in developing reforms, monitor and assess performance, and facilitate community involvement.

We began our work in earnest three and a half years ago. We know that seems like a long time. But achieving transformational change in a large police department does not happen overnight. It takes time and requires rigor. Change that is rushed and haphazard is superficial and unsustainable. The consent decree envisions it will take another several years to attain lasting reform.

Encouragingly, BPD and the city have made considerable progress. They are also moving faster than other big cities that have been under consent decrees. If you compare the reform process to tearing down a house and rebuilding it from the ground up, BPD has laid a new foundation and erected the frame.

BPD has revised or written over 50 core policies, trained officers on those policies, provided specialized training to sex offense investigators, internal affairs detectives, and crisis intervention officers, implemented a fully-modernized electronic reporting system, overhauled its internal affairs function, and reinvigorated its internal audit unit.

For its part, the city, among other things, conducted a detailed analysis of its behavioral health system, and has begun addressing the system’s shortcomings, beginning with a recent pilot program that diverts certain 911 calls involving individuals in crisis to behavioral health specialists.

Tangible signs of change are emerging. BPD’s training academy, once understaffed and listless, is becoming a national model. The number of potentially problematic arrests, particularly for low-level offenses, has rapidly declined following new training. According to The New York Times, BPD was the only one of approximately a dozen major city police departments credited with handling last summer’s protests in a competent, lawful manner—thanks in part to the disciplined organization of community advocates here.

Still, there is a lot more to do—the walls, plumbing, electrical, HVAC, and fixtures all need to be installed and a final punch list completed. To ensure officer accountability and win community trust, the quality of internal affairs investigations must improve. To enable effective supervision and assessment of stops, searches and arrests, officers must properly utilize the field-based, electronic report-writing technology they recently acquired. To adopt a true community policing model, staffing levels, particularly in the patrol division, must increase. And more.

The monitoring team’s 30-month re-assessment published last fall, plus our most recent semi-annual report issued in May, give a full account of BPD’s progress.

The monitoring team encourages community members not only to stay informed, but to participate directly in the consent decree process by sharing your views on draft versions of BPD policies and training lessons and letting us know about your experiences with BPD. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and our website. Attend our quarterly public forums or our bimonthly Facebook Live sessions. Ask us to present at a community meeting. Send us an email at info@bpdmonitor.com, and get on our mailing list. Contact the neighborhood liaison in your police district.

Though a long time coming, change is happening. To fully realize the promise of the consent decree—and to show a watchful country that real reform is attainable—the city needs your engagement.

The opinions on this page are those of the writers and not necessarily those of the AFRO. Send letters to The Afro-American • 145 W. Ostend Street Ste 600, Office #536, Baltimore, MD 21230 or fax to 1-877-570-9297 or e-mail to editor@afro.com

Help us Continue to tell OUR Story and join the AFRO family as a member – subscribers are now members! Join here!

The post Commentary: The Consent Decree makes Baltimore ground zero for police reform appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers .