By “Lady” Brion Gill,

Special to the AFRO

“The Black artist is dangerous. Black art controls the Negro’s’ reality, negates negative influences, and creates positive images.” – Sonia Sanchez

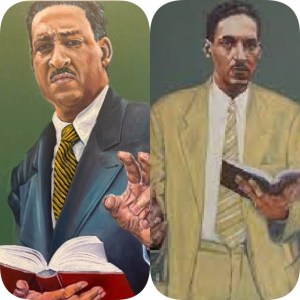

Recently, the Washington Post ran a Jan. 6 article highlighting a painting of Thurgood Marshall by the renowned Baltimore artist, Ernest Shaw. The article prompted this reflection after disclosing that the committee in charge of commissioning the artwork rejected the first painting because it was too aggressive. I happen to know Ernest Shaw and looked at his social media to see if he posted a picture of the first painting.

When I saw the contrast between what got accepted and what got rejected, I couldn’t help but think about this as a metaphor for how Blackness in White-dominated settings is curated and ultimately watered down.

The painting that got accepted has a younger Thurgood Marshall, with a less assertive posture and a loose-fitting suit, conveying a less mature and less threatening image. Black assertiveness in White-dominated spaces are often demonized. Personally, as a spoken word artist, I know all too well what it feels like to have the Blackness in my art minimized. The Baltimore slam poetry team has been characterized as angry for unapologetically critiquing racism or White supremacy in our poems.

In grad school at the University of Baltimore, my professors and classmates would refer to my poems as “speeches” because the content was too radical or political to be considered poetry. And, often when I am asked to write commissioned pieces for institutions across the state, I am asked to “tone down” my words so that the audience can feel inspired rather than uncomfortable.

Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle (LBS) and other organizations that are assertive in our advocacy have experienced attempts at marginalization in order to discourage meaningful challenges to the system of White supremacy.

Art reflects how aspects of a society or culture address themselves to the human experience. The question of what it means to be human is a site of constant cultural and political contestation.

Alfonzo Peter Bailey, a journalist who worked with Malcolm X as the editor of the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU) newsletter called “Blacklash,” once described all art as propaganda. He made this statement on a panel in January of 1993 regarding the release of Spike Lee’s movie, Malcolm X.

In describing his issues with the film, he made the point that Malcolm X was one of the few leaders during the 1960s to call attention to the psychological attacks on Black people’s minds as a result of the system of White supremacy. Mr. Bailey described how movies like Tarzan portrayed Africa as backward, perpetuating the societal propaganda of Black inferiority.

The notion of all art being propaganda helps to explain what is at stake in the contestation of what it means to be human. This society produces art– or propaganda–that advances the systemic dehumanization of people of African descent.

State Sen. Will C. Smith Jr., in the article, said “Just think about how impactful a portrait like this will be for someone that has never seen themselves reflected on the walls of the halls of power….a portrait of a young attorney in the midst of his fight for civil rights will serve as a symbol of hope for all who would come to the committee in search of justice.”

It is true that images and representations have power. The article goes on to talk about the increase in Black elected leadership in Maryland. However, if the images that are most accepted by the centers of power are less “aggressive” figures, then aren’t we just encouraging Black people not to confront the system of White supremacy?

In other words, the folks that commissioned the artwork want to ensure that we don’t encourage Black people who are aggressive.

Black people are not going to be free by finessing White people into including us, as a people, as beneficiaries of their societal power. The art or propaganda that is used to condition Black people into acquiescing to the White imagination’s fear of Black assertiveness has the political consequences of allowing those of us who are assertive to be marginalized.

The committee that commissioned the art and that rejected the first painting is a metaphor for the ways that White institutions seek to water down Blackness. Luckily, we have artists like Ernest Shaw who produce artwork all over the region that depicts Blackness as powerful and assertive.

We should fight for those images to be what our children see.

The opinions on this page are those of the writers and not necessarily those of the AFRO. Send letters to The Afro-American • 233 E. Redwood Street Suite 600G

Baltimore, MD 21202 or fax to 1-877-570-9297 or e-mail to editor@afro.com

Help us Continue to tell OUR Story and join the AFRO family as a member –subscribers are now members! Join here!

The post Commentary: Arts and culture: paint us as we are appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers .

![”[She] Was Special on a Whole Other Level…Something I Never Had Before’](https://nnpa.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Screen-Shot-2022-11-22-at-8.47.27-PM-150x150-1.png)