By Ashleigh Fields

Special to the AFRO

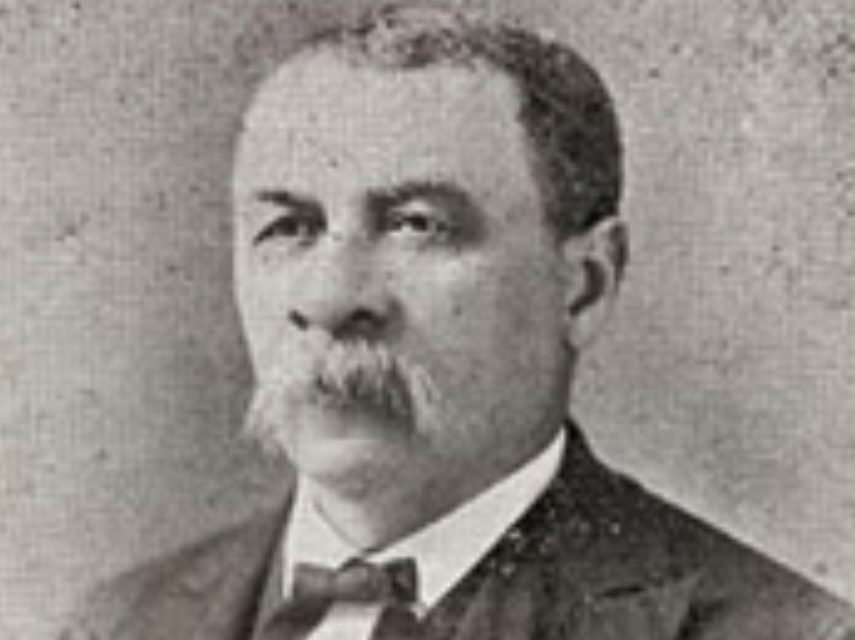

Issac Myers became a pioneering activist in the mid-1800s after years of hard work and labor on ships in the ports of Baltimore. Myers was born a free man in 1835.

Though Myers was free, life was still hard for Black Baltimoreans in the slave state of Maryland. According to information from the American Postal Workers Union (APWU), “he came of age at a time when the city’s schools denied entry to all African-American children, slave or free, but Myers learned to read and write under the tutelage of John Fortie, a Methodist minister.”

Eventually, he made his way to the docks. According to the Maryland State Archives, both Black and White, free and enslaved, worked together in the ports of Baltimore. There, Myers managed to earn wages by caulking and sealing ships, starting at the age of 16 years old.

For a decade he toiled in the trade, reliant on the water lining the City of Baltimore. By 1955, he was working as a supervisor for a major Baltimore ship yard. Myers would leave the ports to work for a wholesale grocery business, but his time at the water’s edge exposed many opportunities to make change for the better.

APWU records report that “in the late 1850s, the caulkers were being paid $1.75 per day — which was more than many White workers earned in similar trades. The high pay did not go unnoticed by shipyard owners and the influx of immigrant workers seeking jobs on the waterfront.”

Soon, riots broke out, and “some shipyard owners refused to hire Black caulkers,” according to the APWU. “At the end of the Civil War, in 1865, White workers staged a successful strike that forced shipyards to dismiss African-Americans. Approximately 1,000 dock workers lost their jobs.”

This would serve as motivation for Myers. In 1866 he returned to the ports with a master plan in mind.

According to the Maryland State Archives, “Kennard’s Wharf at the end of Philpot Street, the very place where Frederick Douglass entered Baltimore as a slave…later became the site of one of the most successful black-owned businesses in Baltimore City, the Chesapeake Marine Railway and Dry Dock Company.”

Myers’ business “employed both Black and White workers, serving as a center of the city’s shipbuilding industry.”

And he didn’t stop there.

In 1868, Myers founded the Colored Caulkers Trade Union Society. At the dawn of a new era, brought on by the end of the Civil War, Myers began protesting worker treatment– and doing something about it.

Eventually, the group was invited to cross racial barriers as a participant in the National Labor Union (NLU) convention, an all White union coalition.

“I speak today for the colored men of the whole country…when I tell you that all they ask for themselves is a fair chance; that you shall be no worse off by giving them that chance….” Myers told NLU leaders in 1869. “The White men of the country have nothing to fear….We desire to have the highest rate of wages that our labor is worth.”

Still, White men rejected Myers’ plan to have the Colored Caulkers Trade Union Society join the National Labor Union as a formal member. Instead, they wanted a separate affiliated organization. In turn, the Colored National Labor Union (CNLU) was created in 1869 by Myers and Douglass as a safe haven for Black workers, with Myers serving as the first president. Douglass was selected as president of the CNLU in 1872, not long before it disbanded.

Much like Douglass, Myers had a passion for politics and remained a high ranking member of the Republican party at a time when it was more aligned with Black interests.

After the CNLU ceased operation, Myers didn’t give up the fight. According to the Organization of Black Maritime Graduates, “he was still organizing groups as well including the Maryland Colored State Industrial Fair Association where he was the president, the Colored Business Men’s Association of Baltimore, the Colored Building and Loan Association and the Aged Ministers Home of the AME Church.”

Later in life, Myers served under President Ulysses S. Grant as a Customs Service agent and as a postal service agent, reporting to Postmaster General John Creswell. According to the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum, Myers is the first known African-American postal inspector, serving from 1870 until 1879. He also became editor of “Colored Citizen,” a newspaper that focused on Black issues.

He died in 1891.

Today, the site where Myers operated his Chesapeake Marine Railway and Dry Dock Company is home to the Living Classrooms Foundation and the Frederick Douglas-Isaac Myers Maritime Park. Visitors can learn about the maritime industry and the rich history rooted in Baltimore, thanks to leaders like Isaac Myers.

The post Caulking the path to progress: Meet Isaac Myers, the man who the sealed the gaps in opportunity for maritime workers appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers.